Studies concerning foreign subsidiary performance have generally focused not only on the role of the parent company such as the ownership advantage, which is frequently measured by the R &D and advertising intensities (Caves, 1982; Lecraw, 1983; Douglas and Craig, 1983), but also on the role of location advantage, which is principally represented in terms of labor cost and market size (Dunning, 1980; Root, 1987; Belderbos and Zou, 2007). In addition, the use of entry modes, such as wholly-owned or joint ventures, has been considered to play a crucial function in subsidiary performance (Chowdhury; 1992; Nitsch et al., 1996; Makino and Beamish, 1998; Pangarkar and Lim, 2003; Carlsson et al., 2005; Belderbos and Zou, 2007). In recent times, however, an increasing amount of attention has been paid to the role of foreign subsidiaries in their own performance as well as on the performance of the entire MNC organization. In this regard, the role of subsidiaries has been emphasized with such concepts as “subsidiary-specific advantages” (Rugman and Verbeke, 2001), “subsidiary initiative” (Birkinshaw et al., 1998), “centers of excellence” (Frost et al., 2002), and “subsidiary capability upgrading” (Luo, 2000; Zhan and Luo, 2008).

Even though previous works have been devoted to the conceptualization of subsidiary roles, they have neglected to provide empirical evidence of the role of subsidiaries on their performance. The principal objectives of this study, therefore, are twofold. The first objective is to make a contribution to the exploration of the attributes of subsidiary roles in relation to performance. The other objective is to empirically evaluate the effects of the role of the subsidiary in its performance. In order to achieve research purposes, we evaluated the role of Korean subsidiaries operating in China and India (which we generally term “CHINDIA”). China has been the largest country for Korean FDIs, whereas India is now considered “Post-China” in the perspective of Korean FDIs. Furthermore, it has been noted that China and India are emerging as the world’s most important new megamarkets for every product (Engardio, 2007). Thus, China and India are the most logical starting points for the evaluations of the roles of subsidiaries because success in these countries is critical, not only to the subsidiaries themselves, but also to parent companies.

Ⅱ. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Recently, a great deal of scholarly work has emphasized the crucial role of foreign subsidiaries on their performance. For instance, Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986) proposed that a subsidiary can become a strategic leader which has a distinctive capability in a strategically important market. According to them, “it must not only be a sensor for detecting signals of changes, but also a help in analyzing the threats and opportunities and developing appropriate responses” (p.90). Thereafter, the importance of the subsidiary role has been emphasized using such concepts as “subsidiary initiative” (Birkinshaw, 1997; Birkinshaw et al., 1998). “subsidiary-specific advantages” (Rugman and Verbeke, 2001; Moore, 2001), and “centers of excellence” (Frost et al., 2002). Indeed, subsidiaries are willing to be entrepreneurial; thus, they commit their resources and build organizational capabilities in order to fully exploit opportunities in advance of competitors when local market conditions are perceived to be favorable (Birkinshaw, 1997). In this sense, Birkinshaw et al. (1998) posited that a subsidiary can become a contributor via the transfer of its innovative ideas and valuable resources to its parent company rather than as the beneficiary recipient of resources from the parent company.

In the same vein, Frost et al. (2002) emphasized the important role of subsidiaries using the concept of “center of excellence”. According to them, the role of subsidiaries as “centers of excellence” is to build up a set of capabilities that creates value. Furthermore, it is important for subsidiaries to maintain an intention to transfer their excellence to their parent companies. As a consequence, the role of a subsidiary as a center of excellence contributes not only to its performance, but also to the performance of its parent company. Luo (2000) and Zhan and Luo (2008) also posited that the transfer of the parents’ monopolistic advantages to their subsidiaries is clearly crucial to the performance of the subsidiaries. However, the more important thing in relation to a subsidiary’s performance is to upgrade its capabilities (i.e., to develop new resources and capabilities through organizational learning to comply with the business environment of the host country). In conclusion, Rugman and Verbeke (2001) regarded subsidiaries’ competences and capabilities as subsidiary-specific advantages. According to them, it is not easy to transfer subsidiary-specific advantages to parent companies and other sister subsidiaries because of the tacitness of subsidiary-specific advantages. Thus, competences and capabilities become different across subsidiaries.

Although the important role of subsidiaries on their performance has been conceptualized in previous studies, little attention has been devoted to examine the factors that constitute subsidiary-specific capabilities. Without determining these, it would be difficult to accurately assess the role of subsidiaries on their performance. In this regard, Birkinshaw et al. (2005) provided two types of subsidiary-specific capabilities. According to them, subsidiary-specific capabilities would be characterized by the role subsidiaries play in exploring local market opportunities and developing new ideas in accordance with local market conditions. In order to explore local market opportunities, furthermore, it would be necessary to expand value chain functions, including procurement, production, R & D, and marketing, in local markets. They also proposed that, in order to develop new ideas in accordance with local market conditions, it would be essential to build close network relationships with local customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and government authorities (Birkinshaw et al., 2005). The former can be referred as “localization capability,” whereas the latter is generally referred as “network capability.”

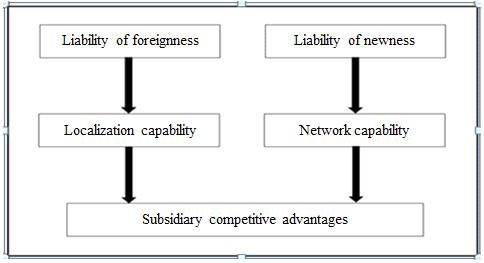

The theoretical validity of localization and network capabilities as subsidiary-specific capabilities can be explained further by using Figure 1. Subsidiaries usually face two types of constraints in host countries. The first constraint is related to the liabilities of foreignness, which are caused primarily by the cultural dissimilarities between the home country and the host country (Hymer, 1976; Dunning, 1980; Zaheer, 1995). The other constraint involves the liabilities of newness, owing to the low levels of subsidiary recognition in local markets. Without overcoming these two constraints, it is hard to expect a favorable subsidiary performance. One way of overcoming the first constraint is to make localization efforts to accommodate local market conditions, which we term “localization capability”.

On the other hand, subsidiaries can overcome their liabilities of newness in host countries by relying on active network relationships with major local entities, including local customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and government authorities (Andersson et al., 2002; Schmid and Schurig, 2003; Scott-Kennel and Enderwick, 2004), which is what we term “network capability”. Network capability provides subsidiaries with legitimacy in local markets, which in turn enables them to procure the information and resources that they lack (Human and Provan, 2000). For example, a study of 97 Swedish MNC subsidiaries demonstrated that the relational business and the technical embeddedness in external networks of foreign subsidiaries perform crucial functions in subsidiary performance due to the easy access of the external partners’ resources (Andersson et al., 2002).

In this study, both localization and network capabilities as the primary roles of foreign subsidiaries are examined to identify their influences on performance.

1. Subsidiary localization capability

Foreign subsidiaries experience the liabilities of foreignness primarily caused by cultural dissimilarities between the home and host markets, as mentioned, which in turn increase the probability of the failure of foreign operations. One method of overcoming the liabilities of foreignness is to adapt to local market conditions. In this regard, the local adaptation of products has been considered very important. According to Kotler (1986), the local adaptation of products satisfies most local consumers’ wants and tastes that are rooted in the local culture. In fact, Still and Hill (1985) reported that U.S. and UK multinationals utilize an active local product adaptation policy over brand, package, design, label, and product ingredients in their host countries, such as those in South America, Southeast Asia, Central America, and Africa.

Douglas and Wind (1986) viewed local product adaptation as a market orientation method. Market orientation involves the realization of marketing concepts via consumer and customer orientation, as well as inter-functional cooperation, which certainly contributes to business performance (Kohli and Jawordki, 1990; Narver and Slater, 1990). Accordingly, it can be assumed that when entering foreign markets that are strategically important in terms of market potential such as China and India, subsidiaries will address localization more closely in order to secure the maximum market performance through satisfying local consumers’ wants and tastes.

2. Subsidiary network capability

New foreign entrants face the liabilities of newness as a consequence of their low recognition in host country markets. This causes difficulties for new foreign entrants in accessing local markets and resources, which in turn increases the probability of business failure (Freeman, Carroll and Hannan, 1983; McDougall et al., 1994; Cavielo and Munro, 1995; Shepherd, 1999; Bradley and Rubach, 1999). One way of overcoming the liabilities of newness is to build strong network relationships with major local entities, including local customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and government authorities. It has been noted that foreign entrants reduce business uncertainties as well as acquire legitimacy with the help of these external organizations’ resources and reputations (Welch and Luostarinen, 1993; Aldrich and Fiol, 1994; Deeds and Hill, 1996; Sadler and Chetty, 2000; Zimmerman and Zeitz, 2002; Zahra et al., 2003).

Indeed, network relationships with key local entities enable subsidiaries to access information and resources that they lack, which in turn contributes to the competitive advantage of the subsidiaries (Andersson et al., 2002 Schmid and Schurig, 2003; Scott-Kennel and Enderwick, 2004). Through network relationships with key entities, for instance, subsidiaries can acquire a variety of benefits, including ideas regarding new product development from suppliers (Dosi, 1988), customer information and market access (Frost et al., 2002), experts from professional institutions (Schmid and Schurig, 2003), and prompt business approvals from government authorities (Bjorkman and Kock). Network relationships also provide subsidiaries with opportunities to learn about unfamiliar local market conditions (Holmlund and Kock, 1997, Westhead et al., 2001). Network relationships are considered to be relatively more important in Asian countries than in Western countries as trust-building needs to proceed prior to starting a business relationship in Asian countries such as China due to a general lack of codified public information and a habit of distrust toward strangers (Bjorkman and Kock, 1995).

The function of network relationships in subsidiary performance has been demonstrated by empirical research. For example, on the basis of an analysis of 141 foreign-owned production firms in Denmark, it has been revealed that business network-related factors, including supplier relationships, advanced user contact, and insight into customers, significantly affect the strength of foreign subsidiaries (Forsgren et al., 1998).

Subsidiary-specific capabilities are of greater necessity when uncertainties prevail in local markets. Competitive intensity has been generally referred to as a proxy for market uncertainty (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Han et al., 1998). In fact, competitive intensity functions as entry barriers for new entrants (Bain, 1956). Thus, as local markets become more competitive, it is imperative for subsidiaries to possess localization and network capabilities for their survival.

It has been previously asserted that local market competition leads foreign subsidiaries to take the initiative in building their own capabilities, which in turn expedites the contributory role of subsidiaries (Birkinshaw et al., 1998). It has been also posited that the influence of subsidiaries’ capability upgrading on performance becomes stronger when local market uncertainties run high (Luo, 2000; Zhan and Luo, 2008).

This study is predicated on Korean FDIs in China and India, the world’s two most populous countries. The reason for selecting these two countries was that China has been the largest beneficiary of FDIs from Korea, whereas India has been considered the most important next-generation market in terms of market potential. With regard to the examination of the efficacy of the role of subsidiaries, the final sample firms were selected on the basis of the following three criteria: (1) operating in manufacturing industries; (2) having operated for more than three years in focal foreign markets; and (3) having more than one million U.S. dollars in terms of the total amount of invested capital. In accordance with these criteria, 686 Chinese and 42 Indian firms were employed as the samples, based on

A questionnaire was mailed to the firms’ directors of international operations who would be knowledgeable of their operations. The first mailing was conducted on September 5, 2007. Due to address changes, disinvestments, response rejection, and unforeseen reasons, 74 out of 686 and 6 out of 42 questionnaires were returned as undeliverable from the sample firms in China and India, respectively. Thus, a total of 612 Chinese and 36 Indian firms were ultimately contacted. Among these, 152 and 16 responses were received from the samples of China and India, respectively, yielding a total combined response rate of 26 percent.

Of the sample, 168 subsidiaries varied considerably in terms of the total amount of invested capital (from 1 million to 70 million USD), with an average of 45 million US dollars. In terms of years in operation, the sample ranged from 3 to 20 years, with an average of 7.97 years. With regard to ownership structure, wholly-owned subsidiaries accounted for 81.5% (137) of the total, whereas joint ventures accounted for 18.5% (31).

Questionnaire surveys inevitably raise concerns about non-response bias and common method bias. First, in order to address the possible non-response bias, the responding firms and a group of 30 randomly selected non-responding firms were compared using secondary data on employee numbers, the total amount of invested capital, subsidiary age, and ownership structure. No significant differences between them were detected.

Because the independent and dependent variables of this study came from the same respondents, there was a possibility of common method bias. Thus, in order to evaluate this bias, Harman’s one factor test was performed (Podakoff and Organ, 1986). A principal components factor analysis of the items associated with the main independent and dependent variables resulted in only three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, the largest factor accounting for only 22.51%. Thus, common methods bias was not a problem.

Since subsidiary performance is frequently determined by a variety of uncontrollable factors, including foreign exchange rates, transfer pricing, subsidies, royalties, and management fees, perceptual measures are the recommended method for the evaluation of subsidiary performance (Killing, 1983; Christmann et al., 1999; Andersson et al., 2001). In addition, perceptual measures have been shown to evidence a strong correlation with objective financial measures such as ROI and ROA in terms of the performance of international joint ventures (Geringer and Hebert, 1991); as such, the perceptual measures of subsidiary performance have been utilized extensively in previous studies (Kotabe and Okoroafo, 1990; Pangarkar and Lim, 2003; Carlsson et al., 2005; Demirbag et al., 2007). Accordingly, this study adopts the perceptual measures of performance.

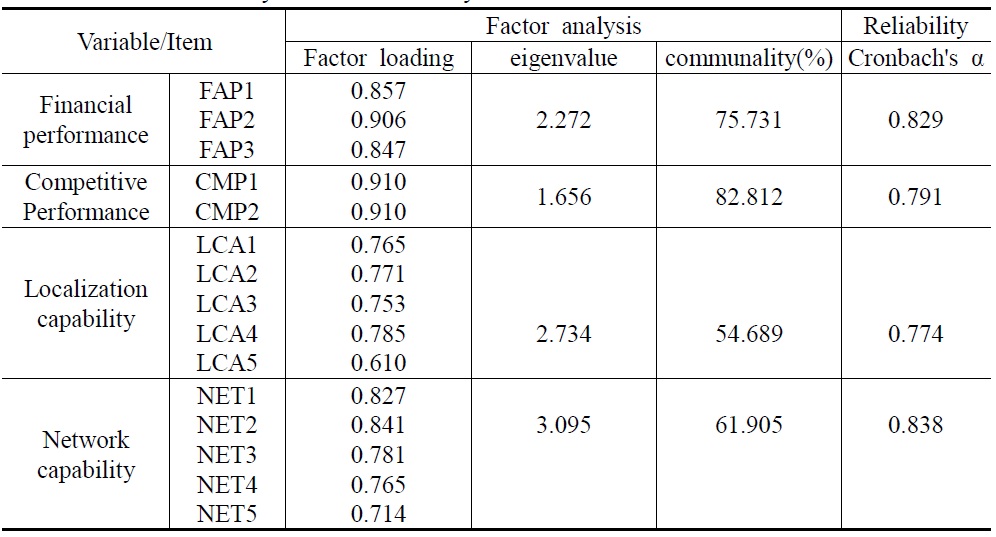

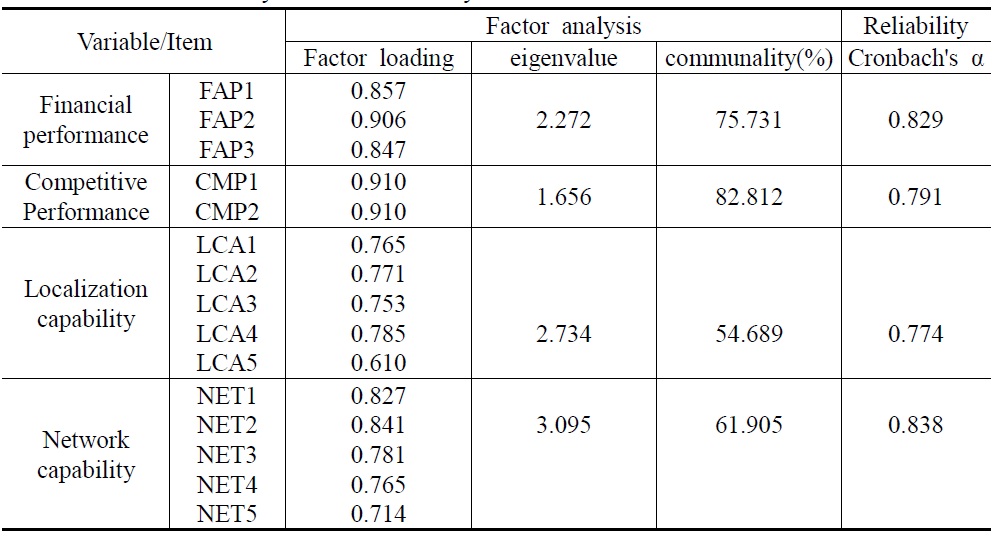

We sorted subsidiary performance into two dimensions (financial performance and competitive performance) as suggested by Zhan and Luo (2008) and measured financial performance by three items (sales volume, sales growth, and sales profitability) and competitive performance by two items (market share and the success of market entry). Measurements using these multiple criteria are expected to help overcome the limitations of narrowly-defined criteria such as standalone sales or profitability, because the goals of subsidiaries from the perspective of their parents are diverse (Glaister and Buckley, 1999; Pangarkar and Lim, 2003). In particular, we asked the following question. Compared to the planned objectives set by the parent for the focal foreign subsidiary, to what extent has the subsidiary actually fulfilled the following performance criteria over the past three years in terms of (1) financial performance (sales volume: FAP1, sales growth: FAP2, and sales profitability:FAP3) and (2) competitive performance (market share: CMP1 and success of market entry: CMP2)? We employed three-year average estimates to minimize the influence of short-term performance variations. A five-point Likert scale (ranging from “very unsatisfactory” to “very satisfactory”) was used to measure the responses. As shown in Table 1, the principal component analysis determined that all items were loaded on a single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.27 for financial performance and an eigenvalue of 1.65 for competitive performance. Cronbach’s alpha (α) values were both in excess of .70, namely .83 and .79 for financial performance and competitive performance, respectively. According to Nunnally (1978), an average inter-item correlation of .70 or above is sufficient to establish scale reliability. Accordingly, the samples evidence a reasonably high degree of adequacy and reliability. Thus, an aggregate measure was constructed by averaging the items for each respondent.

[Table 1] Factor Analysis and Reliability Test

Factor Analysis and Reliability Test

1) Localization capability

We assessed localization capability in terms of the degree to which foreign subsidiaries make efforts at local adaption. Westney (1993) classified subsidiary localization activities into various dimensions such as the local expansion of subsidiary value chains, the increase of subsidiary autonomy in key decision-making, and the localization of subsidiary management systems. We excluded subsidiary autonomy, which appeared to be nearer to organizational control than to localization, in the measurement of localization capability. As such, subsidiary localization capability was measured on the basis of the extent of the localization of subsidiary value chains and management systems. Specifically, we measured localization capabilities using a series of five items: the degree of local adaptation across (1) product specifications (LCA1), (2) product designs (LCA2), (3) promotion and advertising activities (LCA3), (4) business customs (e.g., the terms of contract and payment) (LCA4), and (5) management practices (e.g., labor and personnel management) (LCA5). We utilized a five-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) to measure the responses. All items were loaded on a single factor with an eigenvalue of 3.10 (

2) Network capability

Network capability was assessed in terms of the extent to which foreign subsidiaries maintain active relationships with key local entities. Specifically, this was assessed using a series of five items in accordance to suggestions by Zeng and Lup (2002), Schmid and Schurig (2003), and Chen et al. (2004). These items are active relationships with major local customers (NET1), suppliers (NET2), distributors (NET3), carriers (NET4), and governmental authorities (NET5). A five-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) was utilized to measure the responses. All items were loaded on a single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.73 (

3) Competitive intensity

To measure competitive intensity, we directly asked to what extent is the competitive intensity of the industry in which the subsidiary is now operating. This was also measured using a five-point scale (ranging from “very weak” to “very strong”).

Several variables that may affect the performance of foreign subsidiaries were controlled in this study: parent size, subsidiary age, ownership structure, host country, and industry. Parent size was measured by the number of employees (Pangarkar and Lim, 2003; Demirbag et al., 2007). Subsidiary age, which often reflects experience accumulation, was calculated by the years of subsidiary operation in the host country (Zhao and Luo, 2002; Carlsson et al., 2005; Belderbos and Zou, 2007; Dikova, 2009). In order to control the significant positive skew which is evident for the pre-transformed count measure (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001), parent size and subsidiary age were measured in a logarithmic form. Subsidiary ownership structure was controlled by the use of a dummy variable for a wholly owned subsidiary (taking the value of 1 if a Korean parent held more than a 95% stake) as opposed to a joint venture (Zhao and Luo, 2002; Carlsson et al., 2005; Belderbos and Zou, 2007). Host country effects were controlled using a dummy variable for a subsidiary operation in China (taking the value of 1) as opposed to a subsidiary operation in India. Finally, to control for industry effects, we classified industries into four groups: machinery, electronics, textile, and other industries including chemical industries (the reference group).

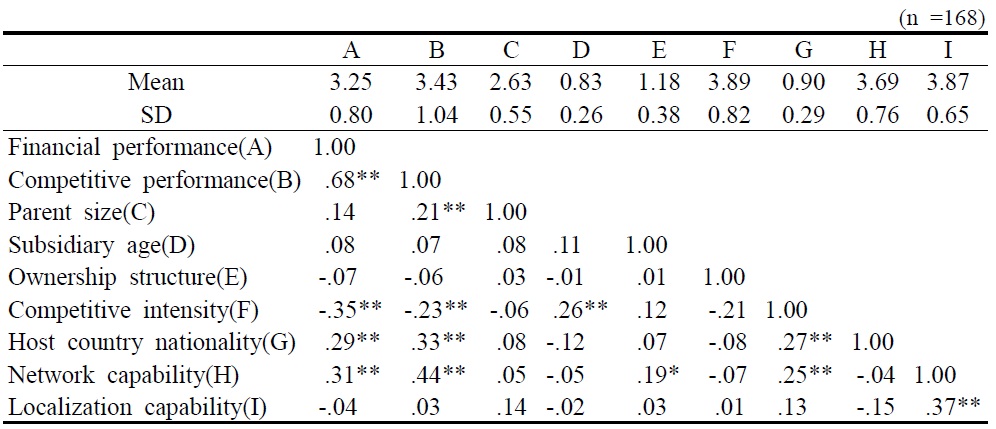

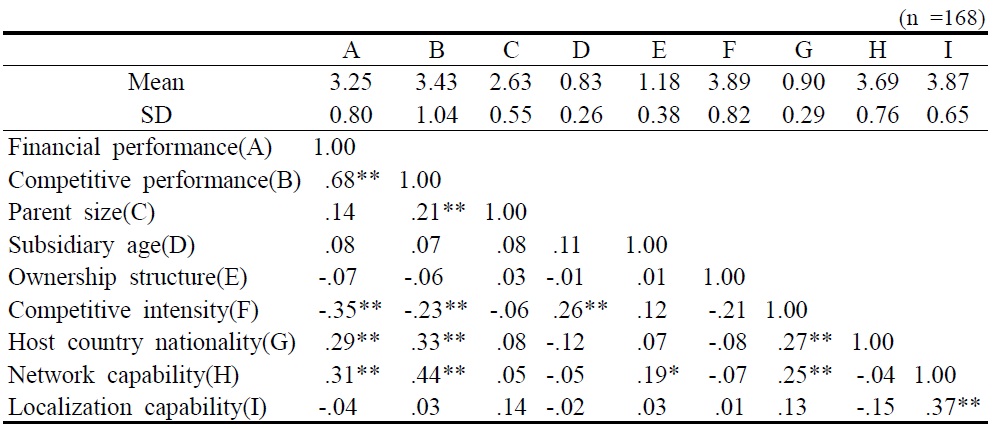

Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations, and correlations for both the independent and dependent variables. The direction of the correlations was generally positive and significant, reflecting the expectations of the research hypotheses.

[Table 2] Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

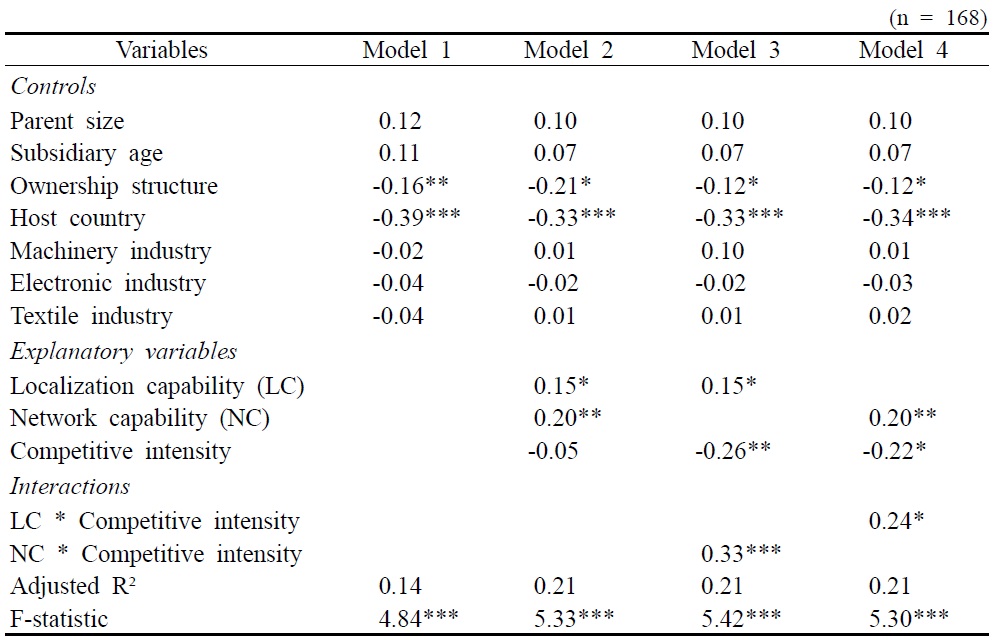

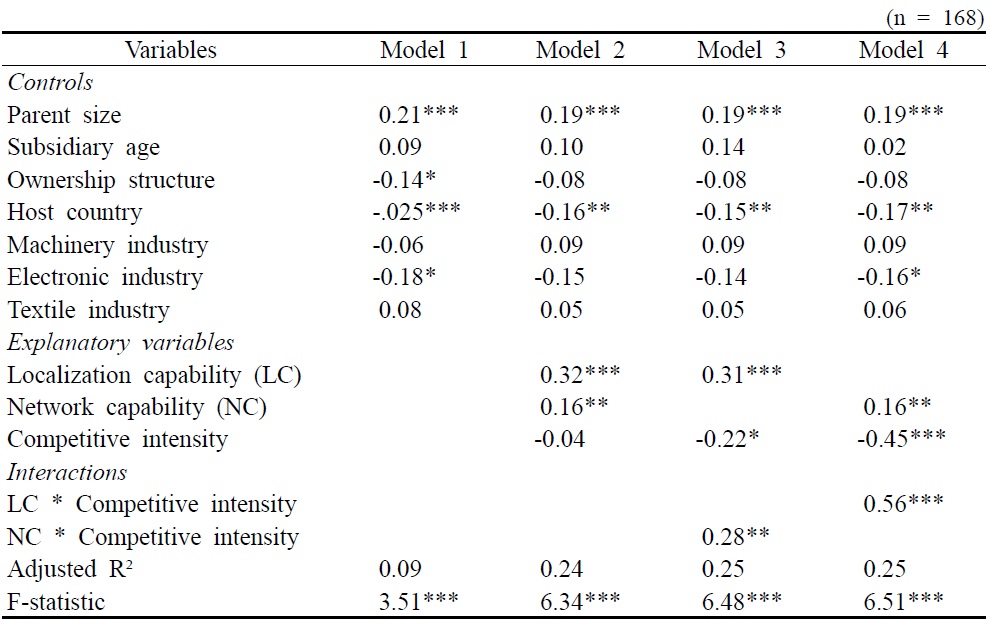

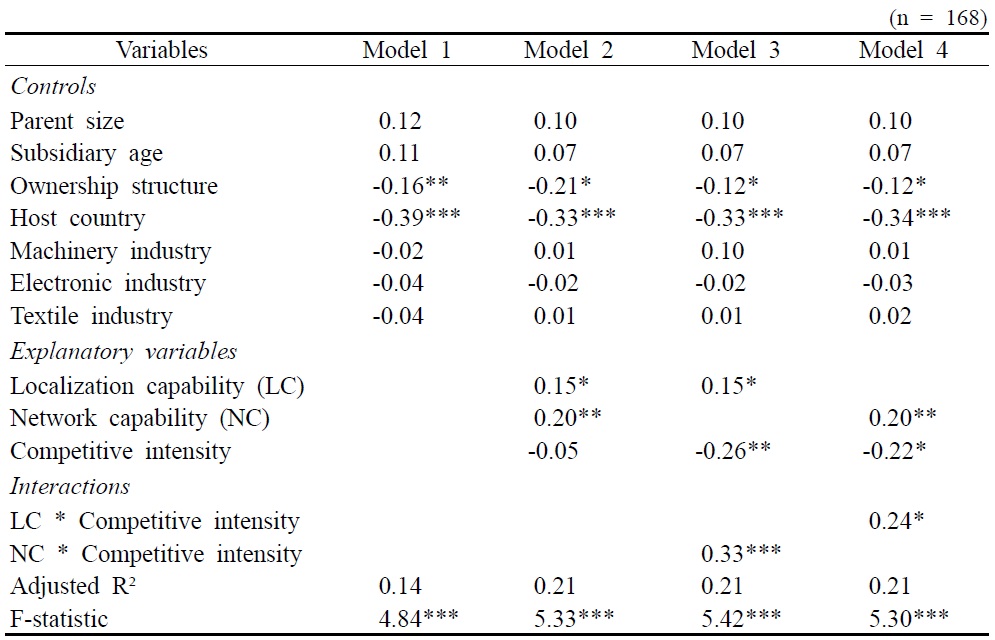

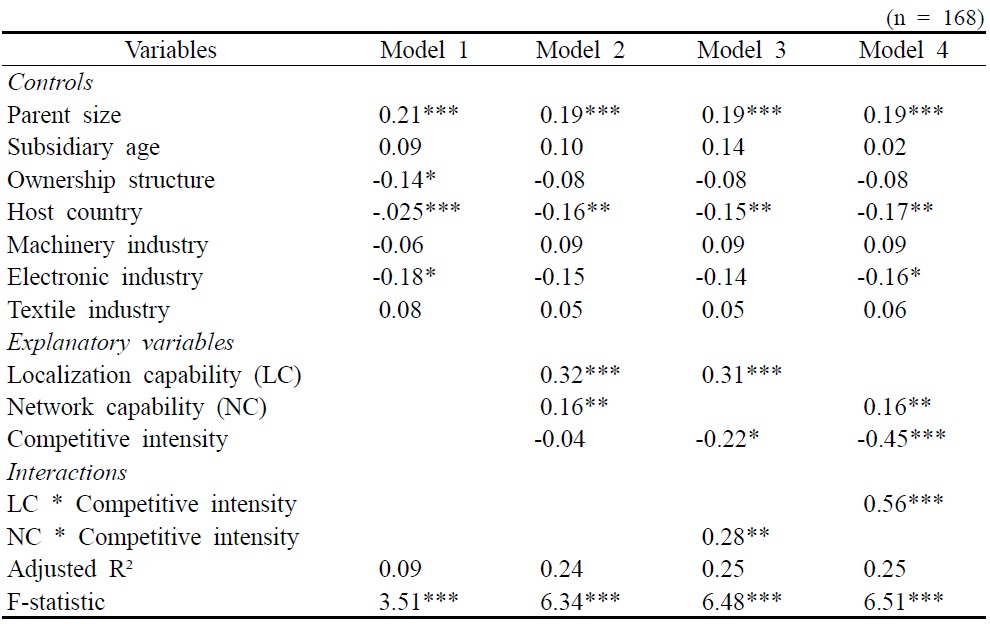

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the regression models for financial performance and competitive performance, respectively, along with the standardized parameter (β) estimates. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) were computed for all of the variables in order to determine their multicollinearity. According to the results of a study conducted by Mason and Perrault (1991), VIFs over 10 are reflective of detrimental multicollinearity. In the case of the full regression model of financial performance with all variables, the resultant VIFs significantly in excess of 10 included network capability (74.84), localization capability (37.28), network capability by localization capability (76.68), network capability by competitive intensity (84.48), and localization capability by competitive intensity (62.07). In the case of the full regression model of competitive performance, the resultant VIFs were similar. In order to prevent multicollinearity problems in regression analyses, variables with VIFs in excess of 10 were covered in a cross-wise manner. As a result, four regression equations were evaluated. Model 1 included only the control variables. Explanatory variables were added to Model 2 such that their main effects could be evaluated. Interaction terms were introduced in Model 3 and Model 4. All four models were determined to be highly significant predictors of foreign subsidiary performance (p < .01 for each model).

[Table 3] Results of Multiple Regression Analysis for Financial Performance

Results of Multiple Regression Analysis for Financial Performance

In Model 1, the control variables collectively elucidated a significant variance (p<.01) in both financial and competitive performance and hence contributed to controlling for effects other than the hypothesized independent variables. In the case of both financial performance (Table 3) and competitive performance (Table 4), it is interesting to note that ownership structure and host country nationality were shown to be significant, thereby indicating their relative importance in comparison to other control variables. In addition to host country nationality and ownership structure, parent size was also shown to be significant (p<.01) in the case of competitive performance. For the industry dummy, only the electronic industry was shown to be marginally significant (p<.1) in competitive performance.

H1 postulates a positive effect of localization capability on subsidiary performance. The coefficient of localization capability was marginally significant with the appropriate sign in Model 2 for financial performance (β = .15; p < .1) and was highly significant with the appropriate sign in Model 2 for competitive performance (β = .32; p < .01). These findings suggest that localization capability plays a more important role in competitive performance than in financial performance and generally support H1.

[Table 4] Results of Multiple Regression Analysis for Competitive Performance

Results of Multiple Regression Analysis for Competitive Performance

H2 predicts a positive effect of network capability on subsidiary performance. The coefficient of network capability was, as expected, highly significant with the appropriate sign in Model 2 for both financial performance (β = .20; p < .05) and competitive performance (β = .16; p < .05). These findings are consistent with the results of a study conducted by Forsgren et al. (1998) that addressed foreign subsidiary performance in Denmark and strongly support H2.

H3-1 predicts a positive effect of the interaction between localization capability and competitive intensity on foreign subsidiary performance. The coefficient for this interaction was, as hypothesized, significant with the appropriate sign in Model 4 for both financial performance (β = .24; p < .1) and competitive performance (β = .56; p < .01). These findings strongly support H3-1.

H3-2 postulates a positive effect of the interaction between network capability and competitive intensity on foreign subsidiary performance. The coefficient for the interaction was, as expected, highly significant with the appropriate sign in Model 3 for both financial performance (β = .33; p < .01) and competitive performance (β = .28; p < .05). These findings strongly support H3-2.

Ⅴ. Discussion and Managerial Implications

This study evaluates the influence of the role of Korean subsidiaries operating in China and India on their performance. Due to the fact that they are the two largest emerging markets in the world in terms of population, success in the Chinese and Indian markets represents long-term growth potential for Korean multinationals. With regard to the subsidiary role on performance, two types of subsidiary-specific capabilities, namely the network and localization capabilities, are proposed in this study. In order to secure subsidiary success in local markets, it is imperative for subsidiaries to overcome not only the liabilities of foreignness, but also the liabilities of newness in those markets. We assume that foreign subsidiaries could overcome the liabilities of foreignness via aggressive adaptation to local markets, while they could overcome the liabilities of newness through the building of active network relationships with key local entities, including local customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and government authorities.

An analysis of 168 Korean subsidiaries operating in China and India shows that localization and network capabilities perform crucial functions in both the financial and competitive performance of foreign subsidiaries. These results bolster the argument that subsidiary-specific capabilities such as localization and network capabilities should be a key initiative option for the successful operation of subsidiaries in foreign markets. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that both localization and network capabilities, coupled with competitive intensity, significantly affect the performance of foreign subsidiaries. This result indicates that both localization and network capabilities are more effective in competitive foreign markets than in non-competitive ones. It is also interesting to note that localization capability has a greater influence on competitive performance (e.g., market share and the success of market entry) than financial performance (e.g., sales and profits). This result suggests that it is imperative for foreign subsidiaries to possess localization capabilities to secure a competitive position in foreign markets. Overall, the results of this study demonstrate the crucial role of subsidiaries on their performance.

The findings provide meaningful implications with regard to the role of subsidiaries on their performance. First, both parent and subsidiary managers must recognize the critical role of subsidiaries, not only in subsidiary performance, but also in the performance of their parents. This is true in the case of subsidiaries that operate in large-sized and strategically important foreign markets such as China and India. In this sense, rather than regarding subsidiaries as short-term profit centers, both parent companies and their subsidiaries should devote their efforts in developing subsidiary-specific capabilities such as localization and network capabilities. In order to achieve this goal, it is imperative that subsidiaries undertake initiatives by themselves rather than relying on their parent companies. Thus, subsidiaries should make every effort to overcome the liabilities of foreignness, which are caused principally by cultural differences between the home and host countries, by pursuing the complete localization of marketing and management practices. In this regard, localization needs to be understood within the context of market orientation as has been suggested by Douglas and Wind (1986). In essence, market orientation involves the realization of marketing concepts with a reliance on consumer and customer orientation, in addition to inter-functional cooperation, leading to outstanding performance (Kohli and Jawordki, 1990; Narver and Slater, 1990). Certainly, market orientation behaviors facilitate the effective localization of foreign subsidiaries.

In addition, subsidiaries should strive to overcome the liabilities of newness in foreign markets by building active network relationships with key local entities such as local customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and government authorities. However, it is not easy to develop favorable network relationships with these local entities. It was recommended, therefore, that foreign subsidiaries should devote their time and efforts to build network relationships not only with local firms but also with local governments for their success, particularly in Asian countries like China (Zeng and Lup, 2002).

However, the problem involves the manner in which foreign subsidiaries develop their own capabilities in foreign markets. In order to realize the abovementioned goals, subsidiary managers need to acknowledge the contributory role of subsidiaries with respect to subsidiary performance, which have been referred to as subsidiary-specific advantages (Rugman and Verbeke, 2001), subsidiary initiative (Birkinshaw et al., 1998), the centers of excellence (Frost et al., 2002), and subsidiary capability upgrading (Luo, 2000; Zhan and Luo, 2008). Rather than relying on parent companies, subsidiary managers should make efforts in developing subsidiary-specific capabilities on their own. It is, of course, imperative that parent companies provide full support, helping to enable their subsidiaries in developing subsidiary-specific capabilities, such as localization and network capabilities. In this respect, it should be kept in mind that the entrepreneurship culture of a parent company must be in place to promote subsidiary initiative. A parent company should encourage its subsidiaries to accumulate their own specific capabilities. The parent also needs to keep criticism and reproach at a minimum level at times of failure, while providing incentives for success. For a foreign subsidiary to actively respond to a changing local business environment, in addition, it is critical that the parent company must grant full trust and autonomy to local subsidiaries. If the parent company tightly controls the decision-making activities of its subsidiaries, it will be really hard for the subsidiaries to nurture and display their own core capabilities.

This study provides a valid basis for future research into the role of foreign subsidiaries on their performance. However, there are several areas that require further research. This study is limited by the operationalization of subsidiary- specific capabilities as the role of subsidiaries. This study proposes two types of subsidiary-specific capabilities, including localization and network capabilities. However, there may be other types of subsidiary-specific capabilities that influence subsidiary performance. Thus, a further examination of subsidiary-specific capabilities is warranted.

In addition, this study addresses Korean subsidiaries operating in China and India. However, the number of Korean subsidiaries in India is still minimal due to the short history of Korean FDIs in India. Thus, the available information is inadequate for deriving a comprehensive overview of the status of Korean subsidiaries in India, making it difficult to compare, between the Chinese and Indian markets, the role of subsidiaries in terms of performance. Such a comparison should be possible, however, when more Korean subsidiaries have been established in India.