This paper analyzes characteristics of architectural design of existing wooden architecture built in the 15th century, focusing on its joints and decorations of framing components and their position. Representative buildings of the first and second half of the 15th century were considered respectively. This study focuses on interpreting architectural characteristics inherited or changed from the late Goryeo dynasty and those settled as main features of architectural design during the Joseon dynasty period and scrutinizing the rationale behind the emergence and transformation of these features.

The 15th century consisting of the reigning period from King Taejong to King Yeonsan was the transition period from Goryeo architecture to Joseon architecture. Restoration of the dynasty was the crux of the 15th century, thus influencing architecture through changes implemented according to new ideology and orientation of the ruling class including the king. Palace architecture and other major architectures such as Jongmyo shrine might have reflected these changes in architectural design resulting from ideological transformation to the highest degree, but unfortunately, most of these buildings were destroyed during the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592. Currently, it is hardly possible to find original buildings of the 15th century within the boundary of Hanyang city, except for Sungnyemun Gate.

Meanwhile, however significant such political incident was, instant transformation of architectural techniques and culture does not happen easily. Some features of architecture could have transformed relatively quickly because of their political and philosophical significance; however, in other features, the establishment of Joseon architecture was gradually accomplished throughout the several decades during the 15th century. It had to incorporate the long-known customs passed down by on-site masters because the Goryeo dynasty in line with gradual changes already emerging since the previous century. These changes were progressed at different speeds per type and region of each building; even disparate parts of the same building sometimes showed different traces of transformation.

Limitation in this study lies in the scarcity of existing wooden architecture of the period. Due to the ravages of the war and the limitation in wooden structure’s durability, the number of existing buildings is not enough for the exhaustive case studies to analyze all changing aspects. Early Joseon dynasty’s architecture and the late Goryeo dynasty’s architecture are often referred to as “yeomalseoncho” architecture together because of the limited number of existing buildings. Yeomalseoncho literally means the late Goryeo dynasty and the early Joseon dynasty. This yeomalseoncho architecture has become the major subject of Korean architectural history as they are often the oldest and the most valuable assets. Current academia classifies existing wooden architecture according to the bracket types, the simple-bracketing style and the multi-bracketing style, a classification that resulted from the early architectural historians’ efforts to categorize the yeomalseoncho architecture according to the style. Therefore, precedent studies focusing on the details of construction and decoration techniques, even if the number of their subjects were limited, can serve as the preliminary basis for understanding the chronological changes.

In this chapter, two Buddhist temples each representing the simple-bracketing and multi-bracketing styles of the first half of the 15th century will be compared. This comparison will show how these styles have inherited each of their traditions and influenced each other in some features. Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple in Gangjin county, built in 1430, and Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple in Andong city, built in 1435,1 are the representative buildings of the early Joseon dynasty period: the former in the simple-bracketing style and the latter in the multi-bracketing style. As their structure and appearance are relatively well-maintained since the initial construction, they have been the major subjects of researches and investigations for a long time. Both of these two buildings are three kan2 by three kan, and they are both a single-storied building with a similarity in its program. Except for these features, they seem to have very little in common. However, when investigated in detail, they share similar design style resulting from contemporaneity.

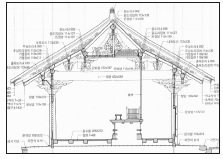

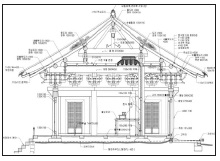

Differences in the architectural design of two buildings are as follows. Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple has a gabled roof with the simple-bracketing style (jusimpo). It has brackets only on the column capitals of the front and rear. However, Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple has a hipped and gabled roof with the multi-bracketing style (dapo). It has brackets both on the column capitals and between the columns of the front, rear, and sides. Also, while a coffered ceiling was installed for only the central kan of Geungnakjeon Hall and side kans were finished with an exposed ceiling, all the interior ceilings of Daeungjeon Hall were covered with the coffered ceiling.

There is also a difference in the framework that supports the beams of the roof structure. Geungnakjeon Hall repeats the manner of how the bracket arms and purlin supports are framed to form the brackets under the eaves on the paryeon-vine-carved supporting plank under ridgepoles and purlins which is placed in line with the column rows of the front and rear. In this way, lintels supporting the roof structure are framed above the bracket arms, and supporting blocks above those lintels are placed in the interval as if installed above hypothetical longer bracket arms to hold up purlin supports. In other words, purlin supports and lintels supporting the roof structure can be included in the simple-bracketing system reproduced indoors. However, in Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple, purlins are supported relatively in a simple manner. The lintels supporting the roof structure are placed between truss posts in the shape of short columns on the beams, and then the layer of simple-brackets is placed between purlin supports and those lintels. These brackets are composed of low hump-shaped supporting boards, bracket arms, and supporting blocks (Lee 2017b, 2-4).

Shapes of each bracket set in these two buildings are very different as well. This difference stems from the inherited techniques of each corresponding style from the late Goryeo dynasty period. In the brackets of Geungnakjeon Hall, bracket arms are joined only on the central axis of the purlins on columns and eave purlins, and both ends of the bracket arms are carved in double S-shapes or more ornate vine-carved shapes. In the composition of cross-purlin (bracket) arms, the heads of two layers of cross-purlin (bracket) arms that extend from the eave purlin supports to the exterior are finished with the intensely curved and sharp soeseo.3 Then, the cross-purlin arm below those two layers was finished with double S-shapes. Above these cross-purlin (bracket) arms, the projecting head of the girder in the central kan, and that of toeryang (a beam of the extended kan) or dantoeryang (a short beam of the extended kan) in the side walls were trimmed in vine-shape and directly joined with the eave purlins and purlins on columns.

However, in the Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple, bracket sets support all eave purlins, purlins on columns, and slipped-in purlins. These bracket sets have shorter and longer bracket arms with round ends which are joined with not only the central axis of the purlins and but also at the intervals to form the inner and outer 2-jump bracket set. Soeseo of the cross-purlin (bracket) arms in the Daeungjeon Hall is different from that in the Geungnakjeon Hall in that its oblique shape faces downward direction uprightly and it is attached to the 2nd cross-purlin arm, which is placed two layers below the eave purlin support. Also, the 1st cross-purlin arm is rounded at the end. Bracket sets between the columns have the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms imitating the 3-cut angular head shape (sambunduhyeong) under the eave purlin support, which were directly joined with the eave purlin support or the eave purlin itself so that there are no building components protruding out. However, in the bracket sets on columns, heotbo (a structural member that mimics a crossbeam head of a bracket set, but not an actual crossbeam head) in the 3-cut angular head shape which even resembles the size of the beam head is joined at the position of the 3rd cross-purlin arm together with the eave purlin and its support (Kim 2016, 145).

The differences in the form and joinery of the bracket arms in these two buildings considerably reflect the periodic characteristics of the simple and the multi-bracketing styles in the late Goryeo dynasty. Also, the difference in the joinery position among soeseo, beam head (or the components emulating the beam head), and the eave purlin support derived from disparate soeseo design of two bracketing styles trying to realize different joinery techniques of ha-ang (the inclined cantilever arms of bracket sets).4 How to support the eave purlin through ha-ang can vary according to the time and region. For instance, the uppermost ha-ang protrudes out right under the eave purlin support, or another component is joined in-between and then ha-ang protrudes out in the layer below. Soeseo design principles seen in many multi-bracketing style buildings during the yeomalseoncho period, including Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple, are similar to the bracketing style introduced in Yingzaofashi 營造法式, an architectural book of the Northern Song dynasty. In this text, shuatou 耍頭5 resembling 3-cut angular head shape was created above the uppermost ha-ang, and the building components serving the function of the eave purlin were joined above this shuatou. On the other hand, the simple-bracketing style of the same period displayed similarities with some cases from ancient Korea or the artifacts of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms or the Northern Song dynasty period discovered in the Fujian province (Lee 2006, 108-74). To sum up, soeseo design of the first half of the 15th century was influenced by the vestiges of ha-ang’s joinery techniques and used in the positions where ha-ang would have been framed in a protruding shape.

Although two buildings look different from each other, there are also clear common features as mentioned above. Among them, the influence that the simple-bracketing style had received from the multi-bracketing style has been known for a long time. Column capitals and supporting blocks of Geungnakjeon Hall, which was constructed before the mid-Goryeo dynasty period, have concave cut base, and concave base with the base support was commonly used for the column capitals and supporting blocks in the simple-bracketing style buildings of the late Goryeo dynasty period. However, in the multi-bracketing style of the same period, relatively simple base for column capitals and supporting blocks was typical. It was an obliquely cut base which was also widely used in the northern China during the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Since the 15th century, this obliquely cut base had become common even in the simple-bracketing style buildings, and Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple is no exception. The section of a beam in Geungnakjeon Hall is in a rounded-tetragonal-shape which was typical in the multi-bracketing style buildings, not a pot-shaped beam commonly used in the simple-bracketing style buildings until the late Goryeo dynasty period.6

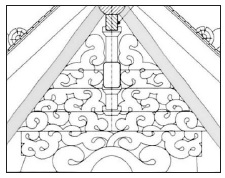

One example of the simple-bracketing style’s influence shown in the Daeungjeon Hall would be the interior finishing of heotbo for the bracket sets on columns on the front and rear. Interior details of these 1st and 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms were rounded as in general multi-bracketing styles since the late Goryeo dynasty to that time period. However, above them, heotbo which is taller and thicker than cross-purlin (bracket) arms was joined. This heotbo seems like a common 3-cut angular head of the multi-bracketing style’s crossbeam in its exterior, but in its interior side, it takes the form of a beam support to buttress the girder above (Kim 2016, 153-54). This kind of heotbo can be also found on the bracket sets on columns of the South Gate in Gaeseong city built in 1392 when was an exact turning point of yeomalseoncho (Kim 2016, 151).7 However, the beam supports of this building’s heotbo display very simple shape, only focusing on its function to support. On the contrary, those of Daeungjeon Hall’s front and rear are carved in paryeon-vine (lotus) shape with strong curves, and the boundary of their patterns form the contour of the beam supports. Daeungjeon Hall of Sudeoksa Temple built in the early 14th century was the first simple-bracketing style building to exhibit two techniques. One was to emphasize paryeon-vine patterns on the surface and contour of the building components, and the other was to use an interior part of the brackets to buttress the beam, thus resembling the shape of the beam support (Lee 2017a, 72-74). These techniques were widely employed in the simple-bracketing style buildings of the 15th century, and Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple is one example.

Of course, there is a clear difference in the active utilization of this paryeon-vine pattern between Geungnakjeon Hall and Daeungjeon Hall. As many parts of the interior bracket sets and the truss post were merged into a part of the paryeon-vine carved component, this paryeon-vine pattern took a major share of the whole interior design in Geungnakjeon Hall. The beam support composed of the interior bracket set was much bigger than that of Daeungjeon Hall in Sudeoksa Temple, forming a large decorative plank with paryeon-vine patterns. Podaegong (the truss post in a shape of the bracket set) with a supporting board was used in Daeungjeon Hall of Sudeoksa Temple. However, in Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple, most framing components were integrated into the truss post with paryeon-vine patterns, except for a few components such as soseul-hapjang (a diagonal support to hold the ridgepoles), soseuljae (a diagonal support to hold the purlins), and other fixed components around the truss post (Lee 2014a, 72-75). Contrary to Geungnakjeon Hall, in Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple, only a few components were finished with the shape of a beam support with paryeon-vine patterns, but the introduction of patterns ultimately leaves room for further consideration in adopting the pattern application methods. After the mid-Joseon dynasty period, the interior bracket sets of the multi-bracketing style buildings were covered with the top-and-bottom integrated paryeon-vine patterns. Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple can be regarded as one of the earlier examples for this transformation. This will be explained further in the next chapter.

Not to consider the whole simple-bracketing style buildings of the Joseon dynasty period, specific comparison between Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple and Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple can reveal commonalities such as the composition of the ceilings. Difference in the construction of coffered ceilings in both buildings was explained before, but there is a possibility that both buildings initially had exposed ceilings, not coffered ceilings. In the central kan of Geungnakjeon Hall, partial dancheong painting can be found in the roof structure of the coffered ceiling, an indicator that it was an exposed ceiling at the time of construction (Cultural Heritage Administration 2004a, 146). Also in the case of Daeungjeon Hall, the roof structure above the coffered ceiling displays an elaborate work, shown in the interior bracket rows supporting the middle purlin and the upper purlin and the upside-down supporting board under the top truss post. Therefore, it is presumed that the ceiling of Daeungjeon Hall was also originally exposed and later changed into the coffered ceiling or the coffered ceiling was added right before the completion of the building. Also, there is an opinion that the simple-bracketing style with the exposed ceiling and multi-bracketing style with the coffered ceiling are typical (Kim 2007, 137). However, the late 14th century’s building, Seonwonjeon Hall in Yeongheung county also has both an exposed ceiling and the layer of interior bracket sets to support purlins. So, it could have been reasonable to have the exposed ceiling with an elaborated roof structure even in the multi-bracketing style buildings until the 15th century.

Coffered ceilings of two buildings also display some similarities. They created a recessed canopy by renovating a certain part of the coffered ceiling above the Buddhist altar in the central kan. Here, the original coffered ceiling was installed without the stepped part (Cultural Heritage Administration 2004a, 146-47; Andong City 2004, 240-44). In the central kan of Geungnakjeon Hall, this canopy takes the size of 6 kan by 4 kan in 8 kan by 8 kan coffered ceiling which was supported by the uppermost beam in line with the middle purlin. Daeungjeon Hall’s central kan has the coffered ceiling of 6 kan by 8 kan installed between slipped-in purlins and the back wall of the Buddhist altar above the level of the girder, and the canopy is 4 kan by 3 kan. Since the coffered ceiling of Daeungjeon Hall is one kan bigger than that of Geungnakjeon Hall, there is no big difference in the actual size of two canopies: 2,449 mm wide in Geungnakjeon Hall and 2,667 mm wide in Daeungjeon Hall. Difference in the height of ceiling, size, and ratio of the canopy is natural because the structure and size of two buildings are different. In both buildings’ back wall of the Buddhist altar, small bracket set supporting beams are installed along the boundaries of the rectangular recessed space towards the ceiling. Above these beams, small bracket sets are tightly arranged and four corner brackets are also placed to form the interior multi-bracket sets. Bracket arms and cross-purlin (bracket) arms are rounded while column capitals and supporting blocks are obliquely cut. One cross-purlin arm of Geungnakjeon Hall and two cross-purlin (bracket) arms of Daeungjeon Hall are finished in the 3-cut angular head shape. Also, two canopies are finished with shingles with two dragons painted. This can be interpreted as a general feature of the recessed canopy, but it is interesting that the recessed canopy, which has been a rare case in Korean Buddhist temples, was applied to these two buildings of the similar period in the early 15th century, especially through reconstructing the ceilings. Predicting when those ceilings were constructed is an intricate issue. But, they do not seem to be added after the mid or late 15th century, considering the simple shape of cross-purlin (bracket) arms in those canopies and the preference of more elaborated shape of bracket sets, stepped ceiling, and canopies after the mid-Joseon dynasty period.

Difference in the details of the canopies indicates that they were not constructed by masters of the same affiliation. First, the frame size for the recessed space differs. In Geungnakjeon Hall, vertical boards are installed around four sides, and cross-purlin (bracket) arms are attached to their inner sides. These cross-purlin (bracket) arms get longer towards the top. Horizontal planks cover the bracket sets on the top, and shingles are placed above. However, in Daeungjeon Hall, rear ends of the bracket set’s cross-purlin (bracket) arms are cut, and inclined boards are attached to those ends. Small space is formed by corbel-shape parts lifting the shingles over the bracket sets.

Composition of the canopy’s bracket sets varies between masters directly exercising the multi-bracketing techniques and masters borrowing the visual imagery of the multi-bracketing style. In the bracket sets of the canopy in Geungnakjeon Hall, only shorter bracket arms are used, and at every chulmok,8 purlin supports are directly joined with those shorter bracket arms. However, in the canopy of Daeungjeon Hall, shorter bracket arms, longer bracket arms, and purlin supports are joined in order to form the bracket set. Also, while there is a hole between cross-purlin (bracket) arms in Geungnakjeon Hall, there is no hole between cross-purlin (bracket) arms in Daeungjeon Hall (Cultural Heritage Administration 2004a, 147; Andong City 2004, 482-83). These features reflect a thorough understanding on the multi-bracketing techniques widely used in the buildings of the time period.

In other words, bracket sets of the canopy in Daeungjeon Hall are composed in more general and legitimate ways of making the multi-bracketing style. This is reasonable because it is the multi-bracketing style building. Yet, those of the canopy in Geungnakjeon Hall are distinguished from other bracket sets of the multi-bracketing style buildings of the time period in their size. However, since this bracket set is only composed of the shorter bracket arms and the size of each part is smaller than usual, the width is about the half of the bracket set in Daeungjeon Hall’s canopy. As a result, nine bracket sets, including the corner brackets, are installed for the canopy’s longer side in Daeungjeon Hall, and 16 bracket sets in Geungnakjeon Hall. In other words, the bracketing style of Geungnakjeon Hall’s canopy deviates from other multi-bracketing style buildings of the same time period, yet it allowed more dense arrangement of bracket sets compared to the similarly sized canopies. It maximizes the visual impression expected from the multi-bracketing style, contrary to the simple-bracketing style.

Based on these characteristics, it can be presumed that masters who participated in the construction of coffered ceilings and canopies for two buildings belonged to different affiliations, each inheriting the simple-bracketing style and the multi-bracketing style. However, regardless of whether the bracket composition comes from the authentic techniques or modified mimicry, aesthetics pursued by those two canopies were based on the multi-bracketing style. Two bracketing styles might have had equal status until the late Goryeo dyansty, or even the 1430s, when two buildings were constructed. Nevertheless, by the time when the canopy was added in Geungnakjeon Hall, luxuriant visual impression of the multi-bracketing style was preferred over the simple-bracketing style.

Comparison of two buildings from the early 15th century in the previous chapter has presented the phenomenon of the simple-bracketing style buildings accepting the architectural design of the multi-bracketing style buildings. Also, the multi-bracketing style buildings were more highly regarded than the simple-bracketing style buildings. However, the multi-bracketing style was also influenced by the simple-bracketing style. Especially through absorbing the progressive transformations of the simple-bracketing style’s architectural design, the multi-bracketing style was renewed in the late 15th century.

Soeseo of the bracket sets in both Geungnakjeon Hall and Daeungjeon Hall derived from imitating and reproducing ha-ang. According to the bracketing techniques, there was a certain rule in the joint location of these inclined cantilever bracket arms, so the placement of soeseo seemed to follow this rule as well. For instance, unless it is as simple as the bracket set with only the 1st cross-purlin (bracket) arms and the beam head in the South Gate of Gaeseong City, the 1st cross-purlin (bracket) arms or heotcheomcha (cross-purlin bracket arms only with an outer end, installed under the capital block) were not decorated in most cases. Also, decorations were applied to the layer right below the eave purlin support in the simple-bracketing style and to the cross-purlin (bracket) arms two layers below the eave purlin support in the multi-bracketing style. Other parts above these layers were not decorated. However, this rule was breaking down by the mid to late 15th century.

Among the existing buildings, the order of soeseo decoration’s position seems to be disturbed since the mid-15th century. In the brackets of Hasadang Hall in Songgwangsa Temple in Suncheon city constructed in 1461, even the bottommost heotcheomcha has soeseo. This case is distinguished from precedent cases in which the bottommost heotcheomcha, if used, was either rounded or carved into double S-shapes in the simple-bracketing style buildings since the late Goryeo dynasty period. As explained above, Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple where heotcheomcha was not used had the end of the 1st cross-purlin (bracket) arms carved in double S-shapes without soeseo. Meanwhile, bracket sets of Hasadang Hall in Songgwangsa Temple display changes not only in the lower part, but also in the upper part. Above the cross-purlin (bracket) arms with soeseo on heotcheomcha and column capital, the beam head framed with the eave purlin and its support is protruding. This beam head is quite short and its end is strongly bent towards the bottom, but it is sharply carved to resemble two soeseo in the below. In other words, Hasadang Hall applied soeseo in the positions with no soeseo formerly. Of course, heotcheomcha without soeseo could be found in the simple-bracketing style buildings until the mid-Joseon dynasty period.9 However, the contour line of this heotcheomcha with soeseo was influenced by paryeon-vine patterns, thus being transformed into ikgong (bird’s wing-shaped bracket arms).10 This transformation was a part of progress towards a new bracketing style of the mid-Joseon dynasty period, called gajeun-sampo style or chulmok- ikgong style, which diverged from the simple-bracketing style during yeomalseoncho period. The status of this new style was in the middle of the multi-bracketing style and muchulmok- kgong style (without inner or outer bracket arms) and widely used in the high-end architecture.11

Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple in Yeoju city is a multi-bracketing style building with a hipped and gabled roof, constructed in 1472. Its frontal bracket sets testify that not only the spread of soeseo design application was carried out without much time difference in both simple-bracketing and multi-bracketing styles, but also they were quite dexterous in establishing new order of bracket design. This bracket set applied a double S-shaped soeseo, modified from the common one used in the simple-bracketing style, for the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms12 and above, and soeseo of the multi-bracketing style was applied to the 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms and below (Lee 2006, 206-11). In this bracket set, the eave purlin support is placed on the 3rd cross-purlin arm, so previous multi-bracketing style would have applied the 3-cut angular head shape in the beam head. However, the simple-bracketing style in which it is common to apply soeseo on the lower part of the eave purlin support is applied, thereby expanding the area of soeseo application. Furthermore, under this bracket set, the multi-bracketing style soeseo is applied to the end of the 1st cross-purlin arm, and the 4th cross-purlin arm supporting the eave purlin arm and its support is protruded with its end carved as soeseo. This soeseo was shorter than that of the 3rd cross-purlin arm, but it was in a perfect shape of the simple-bracketing style’s soeseo.

Soeseo design of Josadang Hall in Silleuksa Temple became the significant prototype of the multi-bracketing style after the mid-Joseon dynasty period. As acknowledged before, cross-purlin (bracket) arms with the simple-bracketing style soeseo gradually transformed into the shape of ikgong. This tendency also appeared in shuatou of the multi-bracketing style which adopted soeseo design of the simple-bracketing style. They were later called ikgong in the multi-bracketing system. Contrary to the lower cross-purlin (bracket) arms with angseo, a type of soeseo that bends downward and sharply raising up the end, they have suseo which is slightly bent upward and declines towards the sharp end. Above this part, ungong (a cloud-shape plank) in various shapes are framed to hold up the eave purlin and its support in general cases.

The simple-bracketing style’s soeseo and the multi-bracketing style’s soeseo are placed up and down in the frontal bracket set of Josadang Hall, a feature that shows the master in charge was fully aware of the traditional design order as well as active in embracing the contemporary changes. In other words, this bracket design realized more abundant use of soeseo design through applying it on many different parts. On the other hand, it is based on a thorough understanding on the original soeseo application in two different bracketing-styles. The upper soeseo reflects the simple-bracketing style because soeseo was first applied to the upper layers of the original simple-bracketing style buildings. Also, the lower part of the bracket sets maintained the soeseo shape of the multi-bracketing style even when soeseo was applied a lot by the simple-bracketing style’s influence. Even though this building’s structure is in the multi-bracketing style, it may have referred to the precedent case of the South Gate in Gaeseong city where soeseo was applied to the 1st cross-purlin (bracket) arms even in smaller bracket sets.13

A tendency to respect the original order and establish new order especially stood out in the frontal corner brackets of Josadang Hall, Silleuksa Temple.14 In Yingzaofashi, one more ha-ang layer was added to the corner bracket on the same level as shuatou in line with the angle rafters, and this was called yu-ang. Between yu-ang and the angle rafter, a piece of a vase called jiaoshen (the angle rafter support 角神) was placed as a structural support and a symbolic function at once. For the corner brackets of Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple, the cross-purlin (bracket) arms joined in front-rear and left-right directions over the column rows have soeseo design applied to the 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms, and the above parts are carved in 3-cut angular head shape, same as in the other bracket sets on and between columns. For handae (a diagonal cross-purlin that stretches under the angle rafter), soeseo is applied to the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms at the same height as shuatou. This soeseo is same as the one applied to the 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms. Then, long upper surface of the 3rd cross-purlin arm is trimmed flat, and extra space is left between the angle rafter and this part as if it were prepared to put on jiaoshen. In other words, the corner bracket set of Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple displays the soeseo design which reproduced the yu-ang order mentioned by Yingzaofashi, and similar cases can be commonly found in the corner brackets of the multi-bracketing buildings prior to the mid-Joseon dynasty period.15

Decorations for the frontal corner brackets of Josadang Hall are dissimilar to those of Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple. This technique did not quite follow the original order but considered the joinery method of yu-ang to a certain degree. As previously mentioned, in the frontal brackets of Josadang Hall, rounded soeseo design is used from the third cross-purlin (bracket) arms at the same level with shuatou and to the other parts above. Cross-purlin (bracket) arms on the frontal corner brackets are in the same shape, stretching towards the front and sides. Also, in handae, 3rd and 4th cross-purlin (bracket) arms had rounded soeseo as well. However, soeseo of the 4th cross-purlin (bracket) arms stretched towards the front, and sides is shorter than that of handae which reaches forward farther and is rounded more intensely with the contour of paryeon-vine pattern. In other words, handae’s 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms were decorated in the shape of the multi-bracketing style’s soeseo at the same level of shuatou as in the corner brackets of Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple, thus being differentiated from the soeseo design order imitating yu-ang techniques.

It is notable that the position where soeseo is hanging is not limited to the front, side cross-purlin (bracket) arms, and diagonal handae. The bracket arms joined to both sides of the corner bracket set penetrate handae and intersect each other; then, at the sections of the support over the bracket arms on the opposite side, the multi-bracketing style soeseo is applied. Since this soeseo is applied at the position where the original ha-ang could never have been framed, this can be the example which overturned the typical order of soeseo design. However, surprisingly, this atypical soeseo design is also applied in the part right next to the simple-bracketing style soeseo on the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms of handae. In other words, the simple-bracketing style soeseo is placed in the direction of original yu-ang protruding, but the multi-bracketing style soeseo is placed on the front and sides as if to make up the missing yu-ang. The master of this bracket set created a completely new order by trying to optimize the coexistence of new tendency to widely apply soeseo design in many parts and the traditional principles of soeseo decoration in both simple and multi-bracketing styles.

The corner bracket set of Josadang Hall in Silleuksa Temple marked a milestone in the corner bracket making techniques of the following Joseon dynasty period. Whatever the original intention was, it opened future possibilities of new soeseo design, advancing from the original techniques focusing on the reproduction of ha-ang’s framing order. Masters of the later generations attempted to actively protrude the end of jwaudae (the bracket arms framed in the both sides of handae in the corner bracket set) and decorated it with soeseo, 3-cut angular head shape, or ungong. Sometimes, they decorated the corner bracket set with various patterns such as the dragon head, phoenix head, or lotus while maintaining their own order around the small sections of the corner bracket set or between this bracket set and surrounding bracket sets.

Another characteristic of Josadang Hall in Silleuksa Temple that is passed onto the later time period is to differentiate the hierarchy of architectural design per each elevation: front, rear, and both sides. To be exact, soeseo design of the front bracket sets, exhaustively explained above, is used on the bracket sets between columns in the front façade and those of the side walls neighboring the frontal corner bracket set. Other bracket sets of the rear and both sides were with less decoration.

Changes in the bracket sets except for those in the corners are separately developed between their upper part and lower part. The 3rd and 4th cross-purlin (bracket) arms gradually merge into one, and the 1st and 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms into one. Transformation steps are slightly different between the upper and lower part, thus presenting the progressive but multi-faceted gradation in their decoration. As to the steps of the upper part’s changes, the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms are decorated with sharply modified 3-cut angular head shape and the 4th cross-purlin (bracket) arms became ungong with rounded end for the bracket sets on the middle column of the side walls and those between the columns neighboring the corner bracket set of the rear and side walls. On the two bracket sets between the middle columns of the rear, ungong of the 4th cross-purlin arm is in more blunt shape. Changes in the lower part are relatively simple. All bracket sets are decorated with soeseo in the front and sides, but the 1st and 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms of the bracket sets in the rear do not have soeseo.

There is a difference in the decoration of the corner bracket sets in the rear and those in the front. The soeseo design for handae in the corner bracket set in the rear and anomalous realization of yu-ang at the height of the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms are same as in the corner bracket sets of the front. However, while three multi-bracketing style soeseo on the end of jwaudae were placed in the front, there were only two in the rear. The 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms on the bracket sets in the rear and sides, next to the corner bracket set of the rear, are decorated in 3-cut angular head shape, same as the neighboring ones. Among the 4th cross-purlin (bracket) arms above, only the right side has ungong with rounded end, like on the bracket sets between columns on its side, but the other three are decorated with the blunt one as in the middle bracket set between columns of the rear.

To sum up, in Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple, a shallow ㄷ-shaped space in the front and a deep ㄷ-shaped space in the rear can be distinguished by the design of the layer of the bracket sets. Also, a ㄱ-shaped space in the rear corner and the middle of the rear display difference in the design of this bracket set layer in the strict sense. Considering the visual difference in the overlapping soeseo in the simple-bracketing style, 3-cut angular head shape, and ungong, masters who constructed this building tried to differentiate each elevation in this small building of 1 kan by 2 kan through varied decorations. The front has the luxuriant upper part of the bracket sets where the simple-bracketing style soeseo was applied, thereby indicating the highest status. Left and right sides are the next, and the rear becomes the most humble side with no soeseo design applied.

Of course, there are some existing buildings built before the first half of the 15th century in which differentiation of architectural design per elevation was applied as a strategy to overcome various practical issues on function and structure. However, Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple is a rare example that displays the apparent hierarchy in bracket design for each elevation. In other buildings, this differentiation resulted from inevitable circumstances of accommodating the structural problem or the need of specific joineries: for instance, the size, number, and position of doors for convenient entrance and daylighting, construction of wooden floors, and the direction of structural composition. The front façade is composed of open space, in general, and the composition of the floor or ceiling can be distinguished between the front and rear because of the location of the Buddhist altar and the space usage pattern. However, the bracket sets are unrelated to these functional issues, and their function to support the roof structure is equivalent in the front and rear. Therefore, the composition and decoration of bracket sets of the existing buildings built before the mid-15th century were similar in the front and rear, if in a single building. Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple remarkably differentiated soeseo design for the bracket sets in its front, rear, and sides; such case cannot be easily found in the buildings before this one. In this building, even the projecting head of the column connecting beam was decorated in the double S-shape in its front and sides while that of the rear was simply cut in section. It is clear that there was an intention to differentiate the status of the rear.

This elevation differentiation technique through varied decoration on the bracket sets or the framing parts in one single building is widely spread and becomes common by the mid-Joseon dynasty period. Also, the means of this differentiation become more active. In the Buddhist temples, the front façade is beautifully decorated with elaborated bracket sets, but the rear had simplified soeseo design for the bracket sets or minimized chulmok, or even the recycled bracket sets from repair works were used. Moreover, double eaves or flower lattice doors were installed in the front while a single eave or simple doors were used for the rear. Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple emphasized its façade only through controlling decorations, but other temples built after the mid-Joseon dynasty period not only employed the dramatic emphasis on the façade, but also attempted cost saving for the rear.

Daeungjeon Hall of Gaesimsa Temple in Seosan city, constructed in 1484, is a multi-bracketing style building with a gabled roof, but its interior design is surprisingly similar to that of Geungnakjeon Hall, Muwisa Temple.16 Convergence of the cross-purlin (bracket) arms in the interior bracket sets is not as refined as in the simple-bracketing style, but it shows a gradual progress. In Daeungjeon Hall of Gaesimsa Temple, interior bracket sets on columns in the central kan display rounded 1st cross-purlin (bracket) arms and 2nd and 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms together forming the beam support integrated within the contour line of paryeon-vine pattern. This shape shows a more advanced convergence of framing parts than in the bracket sets on columns in Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple. The latter is composed of rounded 1st and 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms and only the head of heotbo being finished as a beam support decorated with paryeon-vine pattern. However, the former in Gaesimsa Temple is closer to the interior bracket sets of Geungnakjeon Hall in Muwisa Temple which turned into the beam support. Of course, this building’s exterior bracket sets have upright soeseo in the multi-bracketing style, and the 3rd cross-purlin (bracket) arms on the position of shuatou is in the 3-cut angular head shape. However, soeseo in the multi-bracketing style is applied to both of the 1st and 2nd cross-purlin (bracket) arms, and ungong holds up the eave purlin and its support above the 3-cut angular head shaped part. The exposed ceiling shows the roof structure, and all truss posts are large paryeon-vine patterned posts. These features are very similar to the Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple before the coffered ceiling of the central kan was constructed. Due to these characteristics, this building has long been regarded as a critical case of the multi-bracketing style that adopted the architectural design of the single-bracketing style. Some scholars categorized this building as a hybrid-bracketing style (Yoon 2005, 445-48).

Thorough investigation of the supporting planks in Daeungjeon Hall of Gaesimsa Temple can reveal their difference from those of Geungnakjeon Hall in Muwisa Temple, a difference that marked the beginning of important changes happening in the future generations.17 First of all, soseul-hapjang is framed on both sides of the paryeon vine-carved supporting plank, but the support for soseuljae is completely disappeared. Soseul-hapjang with subtle inward curves in Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple is transformed into an awkward outward shape at the both sides of paryeon vine-carved supporting plank in the central kan of Daeungjeon Hall here. This was to maintain the contour of the paryeon-vine pattern on the truss posts which boast their exaggerated size. However, the supporting planks on both side walls display the sharp contrast in the relationship between the vine-carved supporting plank and soseul-hapjang. They do have vine-patterns on their surface, but their contours do not reflect the paryeon-vine pattern. Their soseul-hapjang is straight, not outward curvilinear as in the central kan to give extra space for the supporting planks. Therefore, at the position where the diagonal soseul-hapjang members are overlapped with the contour of paryeon-vine pattern on the supporting planks of the side walls, this contour vanishes away and instead, takes the diagonal contour like the soseul-hapjang. This is distinguished from Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple where the consistent supporting plank design is maintained for the sides.

Those features of the supporting plank on the side wall of Daeungjeon Hall in Gaesimsa Temple are the consequences of considering structural and construction advantages and decoration effect. First of all, by slightly sacrificing the appearance of this supporting plank, it can strengthen soseul-hapjang’s function because the side wall of the gabled roof buildings should be very sturdy. Straight soseul-hapjang is more efficient in load bearing than curvilinear soseul-hapjang used together with the supporting plank in the central kan. Furthermore, the supporting plank of the side wall is a part of the clay wall that it required the extra plastering work around itself, thus simple shape being more advantageous than elaborated paryeon-vine pattern. Moreover, as the bracket set design in the Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple was differentiated between the front façade and the rear, side walls might have been the reasonable target for simplified shapes. A more extreme case would be the Daeseongjeon Hall in Munmyo shrine, Gangneung city, which was constructed in 1413 and reconstructed in 1486. This building placed the supporting plank with paryeon-vine patterns on the topmost beam, but on its side walls, rectangular planks without specific decoration were used together with supporting planks framed. (Cultural Heritage Administration 2000, 79-80; 137-38). However, Daeungjeon Hall of Gaesimsa Temple did not attempt to use no decoration on the side walls, so it sought for a compromised design.

As a result of soseul-hapjang and supporting planks completely attached to each other, a possibility of their absolute convergence arose. In other words, if two attached components could be inserted within one contour in any case, a separate soseul-hapjang was not necessary any more. Instead, it could be one large plank with simple outlines. Buildings without soseul-hapjang, including the Daeseongjeon Hall in Munmyo shrine mentioned previously, began to appear in the 15th century. By the 17th century, there were only a few buildings with soseul-hapjang in Joseon. Meanwhile, a new simple supporting plank emerged; it focused on the decoration effect more than that on the side wall of Daeseongjeon Hall in Munmyo shrine, but it was easier to construct in the wall than authentic supporting plank with paryeon-vine patterns. One of the early attempts to use the large truss in a trapezoid shape can be found in Ojukheon Hall, presumed to be built in the late 15th century. By 1515, in the main hall of Gunjajeong pavilion in Imchunggak House, it appears in more advanced shape. This large and wide supporting plank seemed to be valued as the second best design after the supporting plank with paryeon-vine pattern. At first, it was mainly used in the parts where the construction was onerous, and since the 17th century, it was used even outside of the walls (Lee 2017a, 77-78).

This paper dealt with several characteristics of bracket sets and interior roof structure’s design of the buildings constructed in the 15th century and explained how these characteristics evolved into the main features of the architectural design during the Joseon dynasty period.

For the early 15th century, Geungnakjeon Hall in Muwisa Temple, constructed in 1430, and Daeungjeon Hall in Bongjeongsa Temple, constructed in 1435, were scrutinized: the former representing the simple-bracketing style and the latter the multi-bracketing style. Their stylistic features confirmed that they inherited each style’s technical principles and decoration techniques. However, they also showed the evidence of contemporary exchanges in adopting each other’s decoration techniques and applying them in the details of the framing components. Two buildings display the traces of different joinery methods in the framing techniques of ha-ang (inclined cantilever bracket arms) inherited by the simple-bracketing style and the multi-bracketing style respectively. Also, purlins, purlin supports, and lintels supporting the roof structure frame follow different framing techniques in the ways of supporting the roof structure. Daeungjeon Hall of Sudeoksa Temple, which is the simple-bracketing style building of the late Goryeo dynasty period (the early 14th century) displays convergence among framing components in its interior bracket sets, a part of which is assimilated into the beam support. This convergence leads to the further change in Geungnakjeon Hall of Muwisa Temple. Here, an interior part of the bracket sets is formed by a large beam support with paryeon-vine patterns, and the vine-carved supporting plank under ridgepoles and purlins of this building also displays such convergence incorporating paryeon-vine patterns. The simple-bracketing style buildings such as this Geungnakjeon Hall quickly adopted some features that emerged in the multi-bracketing style buildings of the late Goryeo dynasty period, such as an obliquely cut base of supporting blocks and column capitals and the rounded tetragonal-shape beam. These simplified features were actively embraced because they contributed to the convenience of fabrication. Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple well exhibits various characteristics of the multi-bracketing style building in its bracket set design and the roof structure supporting method. Paryeon-vine patterns which highly influenced these transformations of the architectural design in the simple-bracketing style buildings were also applied in the multi-bracketing style buildings like Daeungjeon Hall of Bongjeongsa Temple. In this building, they were implemented on the beam supports and ungong, influencing those components’ contour by degrees. Recessed canopies of both Geungnakjeon Hall and Daeungjeon Hall were added after the original time of construction. Even though their details are different, they certainly reflect their preference for visual impression of the multi-bracketing style.

In the late 15th century, while the simple-bracketing style was autonomously changing, the multi-bracketing style shared these changes. Soeseo was applied to other sections deviated from original rules. In the Josadang Hall of Silleuksa Temple, this tendency created a new method of combining soeseo decoration orders of both the simple-bracketing and multi-bracketing styles. It was a preliminary sign for the diverse decoration techniques in the multi-bracketing style buildings of the later period. In the same building, we can also encounter the differentiated hierarchy in the bracket set design of the front, rear, and sides, a differentiation that became a trailblazer of the changes shown after the mid-Joseon dynasty period. The multi-bracketing style building, Daeungjeon Hall of Gaesimsa Temple displays the extended use of soeseo decoration and interior bracket sets with the paryeon-vine patterns assimilated to the beam supports. Also, its paryeon-vine patterned supporting plank on the side wall is almost wholly integrated with soseul-hapjang; several factors behind this integration include the convergence of various components, differentiation of joinery position, and efficiency in wall construction. This is one of the earlier manifestations indicating the decline of soseul-hapjang and the acceptance of the large and wide supporting plank.

The buildings of the early 15th century introduced in this paper showed how the simple-bracketing style and the multi-bracketing style consolidated their own position while inviting each other’s trimming and decorating techniques. However, those of the late 15th century were masterpieces of the skilled masters who thoroughly understood the traditional techniques and tried new experiments that never existed before. Further studies are necessary for the absolute conclusion, but at this moment, it can be interpreted that this transformation was the initial phase of how two independent styles merged into one contemporary style of Joseon architecture with differentiated hierarchy after the mid-Joseon dynasty period.