Sparked by the Park Geun-hye (PGH)-Choi Soon-sil scandal (the Park- Choi scandal) of late October 2016, the Candlelight Protests in South Korea (Korea) saw around 17 million participants in major cities across the country, constituting veritable a citizens’ revolution. Citizen power enabled the seemingly impossible impeachment of the incumbent president, PGH,

The Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 differed from other protests, including previous candlelight protests in Korea.

What motivations compelled so many unaffiliated citizens to join the protest? How could 17 million protesters maintain peaceful demonstrations, avoiding physical confrontation with the police? Most of the existing literature has focused on narrow individual self-interest in examining citizen motivations for joining the protests. By using a unique dataset to analyze the paths that led to Korean citizens joining the Candlelight Protests, this study aims to advance on preceding literature. Building on recent developments in the literature of social psychology, such as political solidarity (Subašić et al. 2008) and moral conviction (Zomeren et al. 2011), as well as work on unaffiliated demonstrators (Klandermans 2014), this study examines motives other than narrow self-interest that led such a large number of unaffiliated citizens from various backgrounds to gather over a short period. In order to do so, this study adopts a twostep strategy for empirical analysis, involving logit analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM). Doing so makes it possible to elucidate the causal paths of the protest.

The paper is organized as follows. The following section discusses the theoretical framework, with a focus on four important factors: injustice, identity, efficacy, and anger. The third section discusses the empirical models, including the data, measurements, and statistics. After discussing the empirical findings, I conclude the paper with comparative implications.

Why do citizens protest? In recent decades, numerous studies have discussed this topic. With regard to the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017, in order to answer the question accurately, it is necessary to distinguish between several important factors such as citizen motivations for participation in protests and then for continuous participation despite obstacles. If the former is the “triggering factor,” the latter is the “success factor.” Previous studies (Lee et al. 2017) and a survey of protest participants (Sogang University 2016a) have indicated that the primary participants in the Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 were not organized dissenters but unaffiliated participants.

Given the characteristics of the 2016–2017 Candlelight Protests, it is important to ask why 17 million unaffiliated citizens joined the demonstrations. A meta-analysis by Zomeren, et al. (2008), on the determinants of collective action, categorized the existing literature into three categories: injustice, efficacy, and identity. Moreover, a recent literature review by Stekelenburg and Klandermans (2013) highlighted three additional factors: emotion, mobilization, and social embeddedness.

Among the most widely discussed factors are citizen grievances and their perception of social injustice. Theories on grievances are delineated into two branches (Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013). The first is the well-known relative deprivation theory (RDT), according to which citizen perceptions that they do not receive what they deserve leads them to collective action. RDT is based on observations that objective deprivation alone does not adequately explain the motive for collective action (Stouffer et al. 1949). RDT further identifies egoistic deprivation, based on personal comparison, and fraternalistic deprivation, based on group comparison (Folger 1986, et al.). The literature also notes that group-based deprivation explains collective action better than individual deprivation does (Postmes et al. 1999; Zomeren et al. 2004). In addition, the affective components of relative deprivation, such as discontent with the distribution of outcomes, are more influential than cognitive components (Zomeren et al. 2008).

In addition to RDT, social justice theory is being increasingly applied to explain the relationship between citizen grievances and protests (Rothmund, et al. 2016; Tyler and Smith 1998). Among the most powerful predictors of protests is the perception of social injustice, be it distributional justice or procedural justice. According to this perspective, those who are marginalized and who perceive an unequal distribution of wealth or unfair treatment may engage in protests.

The second branch of theories on grievances involves understanding that citizen grievances and the perception of injustice are not sufficient conditions for participating in protest; this branch focuses attention on participants’ sense of efficacy. Adopting an instrumental perspective, expectancy-value theory (EVT) emphasizes an individual’s belief that joining a protest is a useful way of redressing grievances or injustice (Corcoran, et al. 2015; Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013). Klandermans’ initial study (1984, 585) categorized expectation into three types, namely: expectation regarding the number of participants, expectation regarding one’s contribution to the probability of success, and expectation regarding the probability of success if many people participate. His longitudinal study of a campaign during the 1979 collective negotiation in the Netherlands confirmed that participants’ expectations are as important as the determinants. Other studies verified that the more citizens identify with groups, the more likely they are to join a protest on behalf of those groups (Mummendey et al. 1999).

In political science, political efficacy is one significant determinant of political behavior. The concept is often delineated into internal efficacy and external efficacy (Campbell et al. 1954). While the first denotes citizen perception of their ability to engage in political behavior, the latter refers to their perception that the government will respond to their wants. Several studies have confirmed a significant relationship between the perception of efficacy and political participation (Beierlein et al 2011; Lee 2010). Corcoran and colleagues (2015) presented a more nuanced analysis, arguing that, whereas internal efficacy is significantly associated with lowand moderate-cost collective action, political efficacy (measured using organizational embeddedness as a proxy) is positively related with low-, moderate-, and high-cost collective action.

Collective identity has attracted scholarly attention because the instrumental account of collective action is inadequate. For instance, according to social identity theory, those who identify with a given social group are more inclined to engage in collective action to enhance the conditions of that group (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Zomeren et al. 2004, 2008). Collective identity refers to the identity shared by members of a relevant group (Klandermans 2014, 2); it also often refers to social identity in the socio-psychological literature. Since it focuses on the individual level, it often denotes more than one group identity.

Other studies have clarified conditions in which the relationship between collective group identification and collective action are possible: the illegitimacy and instability of intergroup relationships, and the impermeability of group boundaries (Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013; Tajfel and Turner 1979; Zomeren et al. 2008). In other words, citizens are inclined to participate in protests if they are not able to exit their group, if they perceive intergroup relations as unstable, or if they perceive the group as having an illegitimate or low status (Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2017). Collective identity may act as an adhesive without which an isolated individual may not join in, given the free-rider option. When citizens engage in political protests on behalf of a group with which they identify, the collective identity of that group is politicized. This is “a form of collective identity underlying group members’ explicit motivations to engage in such a power struggle” (Simon and Klandermans 2001, 323). Collective identity may function as the stepping stone to a politicized identity.

As discussed above, theories of reasons for protesting that focus on the perception of injustice (grievance), efficacy, and identity may provide a theoretical framework through which to explain the 2016–2017 Candlelight Protests. However, to understand how so many unaffiliated citizens gathered so quickly and participated in the protests, it will be beneficial to include an additional factor, namely that of emotion (in particular, anger). Only recently has emotion attracted scholarly attention in the social psychology of protest literature, as it was once considered an error term. However, studies have demonstrated its influence as an accelerator and amplifier (Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2013, 2017).

Applying the above discussion to the Korean case has some limitations, however. First, most of the existing literature, with a few exceptions (Klandermans et al. 2014), focuses on affiliated participation in a protest. However, in many cases, a substantial portion of participants are unaffiliated. According to one study of unaffiliated demonstrators (Klandermans et al. 2014), unaffiliated protesters are mobilized in a very different manner to those who are affiliated. In addition, the strength and the nature of their motivations to join protests vary, as do their patterns of identification. Unaffiliated protesters are mostly reached via open channels. In addition, they identify much more with other participants than with any organization. The Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 exemplify this. As discussed earlier, according to a survey of participants (Sogang University 2016a), the majority did not belong to a political or social organization (96.95%). Most joined the protest with friends or colleagues (50.62%), family (32.71%), or on their own (13.62%).

Second, the existing literature focuses on disadvantaged groups as participants in collective action. However, both disadvantaged and advantaged groups often participate in protests. Furthermore, the latter also express political solidarity, directly or indirectly. According to a survey of participants (Sogang University 2016a), the largest groups in the Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 were college graduates (28.9%), middleincome individuals (25.7%), and white-collar workers (33.1%). Third, the Korean Candlelight Protests did not emanate from merely a transient eruption of anger. There were twenty such protests between October 2016 and May 2017, with over 17 million citizens participating in total.

In the Korean case, it was the people’s political convictions about protecting Korean democracy that enabled citizens of diverse backgrounds to band together beyond their narrow self-interests. Having witnessed the unprecedented misuse of political power by the president, many citizens perceived the situation as a crisis for Korean democracy and, therefore, gathered to protect Korean democracy. Citizens’ slogans at the very beginning of the protests included “Korea is a people’s republic” and “Is this a country?” A demonstration organized by middle-school students in one small city (Wonju, in Gangwon province) symbolized the movement. The protesters said that the “democracy we learned about in textbooks has never been upheld.”

The spirit of the Korean Candlelight Protests may be explained through the idea of “monitory democracy” (Keane 2009). Keane conceptualizes monitory democracy as a form of post-Westminster democracy, paying special attention to the emergence of various types of power-monitoring devices, which function as watch dogs, guide dogs, or barking dogs. In monitory democracy, the exercise of public scrutiny toward the power structure often appears as a new form of offline and online political participation within a digital network structure. Calling the Korean 2016–2017 Candlelight Protests the “cherry blossom uprising,” Keane (2017) argued that a peaceful uprising by a digitally connected citizenry can act as dynamos for the democratization of government power. The case of the Korea Candlelight Protests proves that citizens can change the political power structure outside of “free and fair” elections when an elected government has become—or been perceived to have become— corrupt and has lost public legitimacy.

Background to the Candlelight Protests of 2016?2017

How did this unlikely convergence of a disparate citizenry for a common political cause—the removal or PGH from office—come to pass? It was a media investigation that triggered the Park-Choi scandal, but to better understand the political revolution of the 2016–2017 Candlelight Protests it may be useful to introduce Braudel’s famous perspective, as presented in The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (first published in 1949). Braudel distinguished between three levels of historical time: the longue durée, the conjuncture, and the courte durée. The longue durée refers to very slow and long-term historical structures formed by the interaction between human activity and geography. The term “conjuncture” denotes social, economic, and cultural history, which takes place over an intermediate time span. The courte durée refers to the short-term duration of time in which political events take place.

The protests of 2016–2017 were initiated by citizen anger over the Park-Choi scandal. This might correspond to the courte durée in Braudel’s framework. However, it is noteworthy in this event that there was an intermediate level in which political and economic factors interacted. In Korea, neoliberal political economic regimes were fully developed during the conservative governments of Lee Myung-bak and PGH (from 2008 to 2017), having been initiated by the Kim Dae-jung government during the recovery from the IMF economic crisis of 1997. Accumulating over decades, citizens’ indignation over injustice finally ignited with the Park- Choi scandal.

Given the industrialization it experienced from about 1960 to 1987, Korean society could be characterized as a rags-to-riches story (gaecheoneseo yongnanda). Prior to the economic crisis of 1997, Korea was an open society with social mobility, but after the crisis moving up the social ladder became more difficult. Accordingly, economic inequalities and social polarization became a primary concern of citizens, as confirmed by surveys. The progressive governments of Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moohyun governments (from 1998 to 2008) failed to respond with relevant policies, and the conservative governments (Lee Myung-bak and PGH) from 2008 to 2017 declared a business-friendly government agenda. During this time, the effective corporate tax rate was lowered from 16.90% to 12.90%,

In response to increased economic inequalities and reduced opportunities to advance, citizens harbored strong grievances and deep frustration. Korea’s current young generation is often called the “give-up generation” (Pogisedae in Korean) living in “Joseon hell” (Joseon being the last Korean dynasty, but here representing Korea) because its members have had to sacrifice many things, such as dating and relationships, marriage, family, home ownership, and personal dreams. However, not everyone had to make such sacrifices. Young citizens in Korea identify their class by their family origins, symbolized by a hierarchy of spoons made of different materials, such as diamond, gold, silver, copper, and clay. Such a discourse was indicative of a new hierarchical society (Kang 2017).

Accordingly, the perception of injustice emerged as a salient issue in Korean society, particularly from the time of the Lee Myung-bak administration. One report noted that negative perceptions of social mobility increased in Korea from 75.2% in 2013 to 83.4% in 2017 (HRI 2017). Comparatively, the perception of injustice is also higher among Koreans than among citizens of other democracies. According to the latest Asian Barometer Survey (4th wave),

The Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 can be viewed as a manifestation of accumulated citizen discontent regarding perceived injustice. A prelude that could have indicated the nature of the ensuing candlelight protests emerged about one year before the protests began. Students from Ewha Womans University started a demonstration against the school’s plan to open a lifelong education college. The student protest against the school’s profit-driven expansion escalated with the emergence of suspicions concerning the illegal admission to Ewha Womans University of Jung Yoo-la (or Cheong Yura), the daughter of Choi Soon-sil (the main player in the Park-Choi scandal and a confidant of PGH). In the midst of the scandal over Jung’s admission, a statement posted on her Facebook page just after her acceptance as a student athlete became public, stirring public indignation. In her posting, she said, “If you are incompetent… blame your parents…money is also ability.” The Jung scandal became the catalyst for protests pertaining to the fairness of the university entrance examination process. An analysis was made of comments posted over a period of two months (September-October 2016) in response to an article about the Ewha Womans University scandal on a major news site (Naver). This analysis revealed animosity towards Jung Yoo-la, indicating the moment when citizens’ anger erupted, later consolidating into a nationwide candlelight protest.

Citizen perception of injustice is essentially an individual or groupbased cognition. In the Korean case, injustice entered the public discourse when it escalated to a suspicion about inequalities in opportunity. In particular, this stirred public indignation when it was combined with inflammatory political scandals, such as those surrounding Jung Yoo-la and Park-Choi, which were symbolic infringements of justice. However, the reason that morally indignant citizens joined the protests has yet to be determined.

To answer this question, it is necessary to focus on the role of identity, in particular the preference for democracy, in combination with the roles of efficacy and citizen anger. I discuss the role of identity first. During the Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) and PGH (2013–2017) governments, there were serious debates about democratic setbacks. With the inauguration of the Lee Myung-bak government, Korea passed the so-called two turnover test, meaning that democracy had been consolidated at the level of the electoral regime (Hahm 2008). However, the evaluation of the quality of democracy during that time yielded retrograde results. According to the Freedom House index, the overall freedom rating in Korea worsened from 1.5 to 2 in 2014, because of a degradation in political rights (from 1 to 3) for the first time since 2005. Similarly, in 2015, the democracy index of the Economist Intelligence Unit categorized Korea as a flawed democracy for the first time since 2008.

The Park-Choi scandal occurred in the midst of a democratic retreat. This realization served as a reminder of the significance of democracy. Compared to six months previous (June 2016), the percentage of Korean citizens believing that democracy was better than other forms of government increased during the Candlelight Protests (December 2016), from 52.75 percent to 75.5 percent. Moreover, during this same period the percentage of those who believed that, in some circumstances, dictatorship was better than democracy decreased, from 28.6 percent to 15.2 percent. This change occurred across the party-political spectrum (Lee et al. 2017, 143–148), as shown in Table 1.

[Table 1.] Change in Support for Democracy by Partisanship

Change in Support for Democracy by Partisanship

Many citizens understood the Park-Choi scandal as a crisis of democracy and expressed their readiness to defend democracy by joining the Candlelight Protests. Indeed, more than four-fifths of participants (83.97%) supported democracy, a higher percentage than non-participants (74.97%). Furthermore, in some respects, the protest was a political expression of opposition to the PGH government. However, even though the largest group of participants identified themselves as progressive (39.1%), similar participation rates emerged among centrists and conservatives (19.4% and 17.3%, respectively). Moreover, of those in their fifties who participated in the protests, around a quarter of them (23.63%) self-identified as early PGH supporters. In addition, slightly less than two-thirds of participants in their fifties (62.45%) said they would have been willing to participate further if PGH had not stepped down. During the nationwide Candlelight Protests, numerous smaller protests to defend democracy were voluntarily organized by unaffiliated citizens. For example, around 200 high school and middle school students hosted a rally to defend democracy in their local city. Their main slogan was “Where is the democracy we learned about in school?”

Also of importance to the participants was whether their participation would bring about change. Before the candlelight protests, there were the three minjung (often referred to as the lower class, including laborers, farmers, and ordinary urban citizens) general rallies protesting the PGH government’s neoliberal labor reforms and destruction of the welfare of ordinary citizens. At the first rally, Baek Nam-ki, a farmer, was knocked over by a police water cannon and eventually died after a year in a coma.

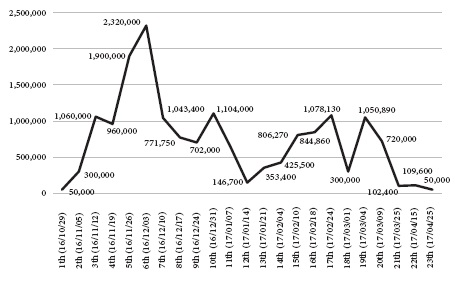

The most intriguing issue regarding the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017 is how 17 million citizens participated in the protests, since they were largely unorganized and engaged in peaceful protests without a single arrest. Figure 1 graphically represents the change in the number of participants from the first to twenty-third Candlelight Protests. The first protest saw 50,000 citizens, a number that reached 2.3 million by the sixth protest, which marked the turning point.

Given the number of seats of each party at that time (the incumbent Saenuri Party with 128 seats, the Democratic Party [DP] with 121 seats, the People’s Party with 38 seats, the Justice Party with 6 seats, and independents with 7 seats), without the division of the incumbent party, it would have been impossible to ratify the impeachment in the National Assembly. The political factions in conflict with President Park supported the impeachment procedure after a special investigation highlighted the president as a suspect in the Choi Soon-sil scandal. However, with President Park’s third statement to the nation, they shifted their position, opting not to join the impeachment process. As a result, a serious division emerged in the impeachment coalition, which increased citizen concerns about the impossibility of passing the impeachment bill. At this point, the largest assembly of citizens gathered in protest (up to 2.32 million people). With mounting citizen anger, the anti-Park factions in Congress decided once more to join the impeachment process.

One factor that might explain how a large-scale rally comprising mostly unaffiliated citizen participants could take place is the participants’ firm conviction that their efforts would eventually bear fruit. According to a survey of participants (Sogang University 2016a), most respondents (87.85%) believed that their participation would influence whether or not President Park stepped down. In addition, a similar number of respondents (88.82%) said that experiencing the Candlelight Protests made them believe more in the importance of civic awareness. This effect is also found in the comparison between participants and non-participants. According to one survey (Sogang University 2016b), rates for positive perceptions of political efficacy was about 20 percent higher among surveyed participants (68.16%) than among surveyed non-participants (49.88%). Even though most participants were unaffiliated, they could establish solidarity during the protests by sharing their life experiences. While the Park-Choi scandal convinced citizens of the importance of politics, the unexpected number of citizens gathering and their political impact (in particular, the sixth protest on December 26, 2016) reinforced citizen belief in the importance of political involvement.

During the Candlelight Protests, a forum or agora provided an outlet through which participants could freely express their frustrations, anger, and political views. This was “the moment of madness” (Zolberg 1972). However, the organizers of the Candlelight Protests made every effort to maintain a peaceful rally in order to avoid providing any motive for ruling forces to counterattack.

This study argues that, to accurately examine citizen motives in joining the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017, a theoretical framework to explain citizen responses to the different dimensions of the Park-Choi scandal must be formulated. Specifically, the unexpected explosion of citizen anger toward the president’s misuse of power, officially delegated from the citizens, needs to be explained. Citizens’ accumulated grievances over injustices were underlying factor. The Jung Yoo-la and Park-Choi scandals originated from a back-scratching alliance between the government and a large conglomerate. This triggered citizen’s accumulated discontent over the injustices of Korean society.

To test the arguments, this study employed a unique dataset generated by the Center for Contemporary Politics of Sogang University in December 2016 during the final stage of the Candlelight Protests in Korea (Sogang University 2016b). A survey was conducted from December 26 to December 28, 2016. The total sample size was 12,000 individuals. The response rate was 15.2%. The survey was conducted by telephone interview through random digital dialing. Given the focus of this study, this survey seems to be the most appropriate. First, the timing of the survey was soon after the climax of the protests on December 9, the day the impeachment bill was passed following the sixth candlelight protest. Three more candlelight protests took place prior to the survey. Second, this survey featured a significant questionnaire that inquired into political attitudes and whether respondents had participated in the protests and intended to join the protests again. Third, the respondents included both participants and non-participants, making it possible to examine determinants to participation in the candlelight protests.

The dependent variable was citizen intention to participate again in the candlelight protests against the Park-Choi scandal if President Park did not step down. I created a dummy variable, assigning “1” to those who would participate in the protest again and “0” to those who would not. Given the purpose of the protests and the fact that the survey was conducted in the middle thereof, questions that measured citizen intention of joining the protest again were considered a more relevant measure than whether they had participated in previous protests.

To test the argument, the study employed a two-step empirical strategy. In the first stage, logit analysis was conducted to test the determinants of citizen intention to rejoin the protests. In the second stage, SEM was employed to scrutinize the interrelations among the significant independent variables in determining the dependent variable.

Four primary independent variables were employed: perception of injustice, identity, efficacy, and anger. First, the perception of injustice was measured on the basis of four variables: wealth distribution, just treatment, disparity between rich and poor, and social mobility. These variables were measured through responses to the following questions: “How fair do you think the distribution of wealth is in our society?” (1: Very fair to 4: Very unfair); “What do you think about your social treatment compared to your efforts?” (1: Very high to 5: Very low); “What do you think about the disparity between the rich and poor?” (Originally coded ranging from 1: Serious to 4: Not serious, but recoded in the opposite direction); and “Do you think everyone can move up to a higher position in the social hierarchy if they make an effort?” (1: Very much so to 5: No, not at all).

Second, identity was measured through two variables: preference for democracy and the citizen’s political ideology (progressive). The preference for democracy was measured by responses to the question “Which of the following statements most closely resembles your own opinion? 1) Democracy is always preferable to any other kind of government; 2) In some circumstances, an authoritarian government is preferable to a democratic one; and 3) For people like me, it does not matter whether we have a democratic or non-democratic regime.” For those who preferred democracy to other types of government, I created a dummy variable, assigning “1” to those who preferred a democratic government and “0” to the others. In addition, progressive ideology was based on self-reported ideology. I created a dummy variable for those whose ideology was reported as progressive.

Third, efficacy was measured through two variables: perception of efficacy and significance of politics. Perception of efficacy was based on responses to the question “For people like me, there is no point talking about what the government is doing” (1: Strongly agree to 4: Strongly disagree). The significance of politics was measured by responses to the question “Can politics make a significant difference to you?” (1: Yes, 2: No). For those who replied “yes,” I created a dummy variable, assigning “1” to them and “0” otherwise.

Fourth, anger was measured on the basis of the respondents’ assessment of the main reason for the Choi-Park scandal. The variable of Park’s rule as the main cause of the Park-Choi scandal was measured on the basis of responses to the question “What do you consider to be the main cause of the Choi-Park scandal?” (1: President’s corrupt rule, 2: Power structure excessively vested in the president, or 3: Cohesion of the Chaebols [the rich], bureaucrats, and prosecutors). For those who selected the president’s corrupt rule, I created dummy variables, assigning “1” for respondents who selected the president’s corrupt rule, and “0” otherwise. A second variable, concerning responsibility for the political conflict during the Park administration, was measured on the basis of responses to the question “Who do you think is responsible for the political conflicts during the Park administration?” (1: President PGH, 2. The ruling party (SNR), or 3. The opposition parties, including the DP). I created a dummy variable for those who chose President PGH.

Besides the four main variables’ direct causal paths to the decision to protest, there may have been interrelationships among them. As discussed earlier, the exacerbation of economic inequalities and social polarization over several decades became significant public issues in Korean society. Having witnessed an unprecedented triangle of corruption scandals involving the president, Samsung, and Choi Soon-sil, the last as an unofficial key advisor to the president, critical perceptions of socioeconomic injustice among the Korean citizenry could be significantly related to their faith in, and preference for, democracy. Citizen identity (their faith in democracy and ideology) could also have influenced their perceptions of the efficacy of protest and their level of anger.

Table 2. Comparison between Socioeconomic Conditions of Participants and Non-Participants Variables Participation Non-participation

Comparison between Socioeconomic Conditions of Participants and Non-Participants Variables Participation Non-participation

Table 2 compares the socioeconomic backgrounds of participants and nonparticipants. Around a quarter of respondents (24.19%) reported they had participated in the Candlelight Protests.

First, with regard to gender, among all those surveyed a higher percentage among men (28.11%) than women (20.33%) reported to have participated in the protests. The relatively lower rate of participation among women may be attributable to the fact that housewives were hampered from participating due to the start time (6 p.m.) of most protests. As seen in Table 2, among professions, housewives reported a participation rate of only 11.21 percent. No noticeable gender difference was evident in other occupational groups.

Second, with regard to generational differences, the participation rate for those in their 20s, 30s, and 40s was about 30 percent (30.52%, 29.36%, and 29.53% respectively), higher than that for those in their 50s (23.63%). The participation rate of the group aged more than 60 years was 10.83%. The Candlelight Protests were not the brainchild of the young generation alone.

Third, regarding the effect of education, the higher the level of education, the higher the participation rate (9.38% for those with only a middle-school education and 28.96% among college graduates).

Fourth, there was no linear relationship between income level and participation rate. However, those in higher income groups were more likely to participate, excepting those in the 350–450 million Korean won (KRW) bracket. The highest participation rate was among the highest income group (32.07%).

Fifth, for the effect of occupation, the highest participation rate was for white-collar workers, such as office management professionals (33.33%), followed by students (31.43%), and blue-collar workers, such as manufacturing and technical workers (29.85%). The two groups with the lowest participation rate were those who worked in a primary industry (4.88%) and housewives (11.21%). Last, as expected, the highest participation rate was among progressives group (39.00%). Participation rates among self-identified centrists and conservatives were similar.

[Table 3.] Logit Analysis of Determinants of Citizen Decision to Rejoin Protests

Logit Analysis of Determinants of Citizen Decision to Rejoin Protests

The results of the logit analysis are presented in Table 3. Overall, the results confirmed the theoretical expectations of this study. First, among the variables for injustice, three variables other than the rich-poor disparity turned out to be significant. Those who believed they did not receive treatment deserving of their efforts, those who held a negative view of social mobility, and those who perceived an injustice in wealth distribution were more inclined to rejoin the protests. On the basis of the odds ratio, it is possible to say that the effect of injustice in wealth distribution was largest (1.775). Second, two variables that tapped into identity were also found to be significant variables. As discussed in the theoretical framework section (monitory democracy), citizens who felt there was a crisis of democracy spilled into the streets. In addition, even though participants’ ideological backgrounds were not narrow, those who held to a progressive ideology were more inclined to join the protests again. The odds ratio indicates that the effect of the preference for democracy was second largest, after DP identification. Third, as the proximate cause of the scandal, citizen belief in the president’s responsibility was identified as an important factor in their inclination to join the protests again. Similarly, citizen attribution of responsibility for the political conflict to the president turned out to be a significant factor.

Fourth, all control variables except education were found to be important determinants. Among the strongest determinants was DP identification (odds ratio, 3.212). By contrast, partisanship with the incumbent (SNR identification) had a significant countervailing influence on citizen intention to protest again. In addition, the younger the cohort, the greater the intention to protest again, and men were more likely than women to participate in the protest again. Interestingly, household income had a positive influence on citizen intention to protest again. As discussed above, grievance theory alone cannot explain the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017.

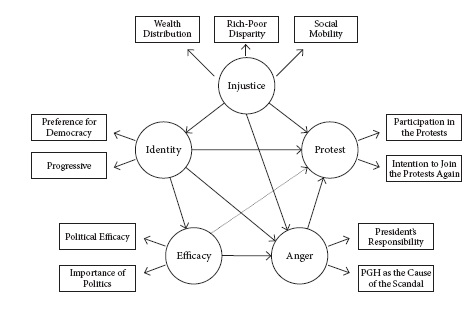

To further elaborate the relationship between the independent variables and citizen participation in the protests, SEM was used (STATA 14 software). Employing SEM enabled us to examine various causal relationship pathways. Table 3 shows the direct/indirect and total effects of the variables on citizen protesting. In order to conduct SEM, five latent variables were created (injustice, identity, efficacy, anger, and protest). We have discussed four of these latent variables above. Protest was measured by two variables: where the respondents participated in the protest and whether they intended to join the protests again.

Overall, SEM vindicated the theoretical expectations of this study, confirming all expected routes as significant except the path between identity and protest. The model was based on the logit regression results presented in Table 3. Figure 2 shows the interrelationships among the variables. As for the fit of the model, overall major indices of the model fit show that there is good fit for the statistical model. CFI (0.974) and TLI (0.960) scores were close to 1.00. In addition, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) score (0.027) indicated good fit.

[Table 4.] Standardized Coefficients/Direct/Indirect Effects and Total Effects of Variables

Standardized Coefficients/Direct/Indirect Effects and Total Effects of Variables

Citizen intention to join the protests to force President Park to step down was significantly associated with perception of injustice, measured by three observed variables (wealth distribution, rich-poor disparity, social mobility), with shared identity, measured by two observed variables (preference of democracy, progressive), and by anger, measured by two variables related to the cause of the scandal.

We now discuss the latent injustice variable, which was measured on the basis of three observed variables. The total effects of injustice were the second largest. Its standardized coefficient was 0.169 and its total effect was 0.357 (Table 4). All three observed variables were found to be significant. As with the results from the logit analysis (see Table 3), of the three observed variables, critical citizen views of wealth distribution had the largest effect on their intention to participate again in the protests. When the standardized coefficient of “wealth distribution” is 1, those of “rich-poor disparity” and “social mobility” are 0.574 and 0.754, respectively.

Injustice both directly and indirectly affected the citizen protests. Underlying the protests was indignation at the injustice of Korean democracy. It would be useful to emphasize that the main characteristic of the scandal was the collusion between business, represented by Samsung, and political power in Korea democracy. Economic inequality had increased since the IMF economic crisis, particularly during the conservative government era. Using Braudel’s metaphor, this corresponds to histoire conjuncture. As discussed above, the Jung university entrance scandal was the catalyst for the protests, and as recent studies show (Rothmund et al. 2016), sensitivity to justice could explain individual differences in political engagement. There was an indirect path between injustice and protest, via identity and anger.

At the intermediate level, identity also had a significant direct and indirect influence on citizens’ decision to protest. Those who held a preference for democracy and whose political ideology was progressive were more inclined to join the protests. Of the four latent variables, identity had the largest effect on the protests. Its standardized coefficient was 0.771, and its total effect was 1.554. There was an indirect path between identity and protest through efficacy and anger. Efficacy, which is identified in the extant literature as one of the significant determinants of individuals’ decision to protest, was not found to be an important determinant. Citizens’ anger, measured through two variables, turned out to be a significant determinant.

Citizens who witnessed the president’s privatization of officially delegated power were infuriated and descended onto the streets. Since anger was the proximate cause, there were no other indirect effects to protest via other paths. The survey employed in this study did not include questions measuring the indignation of citizens because emotion has only attracted scholarly attention in recent decades. Thus, emotion may play a role during all stages of protest recruitment, maintenance, and dropping out (Japser 1998). A typical emotion during a protest is anger (Stekelenburg and Klandermans 2007, 2017). According to a survey of participants alone (Sogang University 2016a), their anger toward the Park-Choi scandal was overwhelming, recorded as averaging 9.30 (on a scale from 0–10).

The purpose of this study was to examine the determinants of citizen participation in the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017. The protests were unprecedented in terms of the number of participants, the breadth of the participants’ socioeconomic and political backgrounds, their nonviolent nature, and their political consequences. In order to examine the multi-layered nature of the Candlelight Protests, this study adopted a twostep empirical strategy: logit analysis and SEM. By employing SEM, the study was able to confirm the interrelationships among the four main latent variables. This study argues that the existing literature has not paid sufficient attention to the reasons so many unorganized citizens joined the protest beyond their narrow economic interests.

The main empirical findings can be summarized as follows. First, overall, both statistical models confirmed the main arguments of this study, showing that citizen decision to protest emanated from a response to events, involving a multi-layered structure: injustice, identity, and anger all played a role. By employing SEM, this study was able to determine the interrelationships among the different dimensions influencing the citizen decision to protest.

Second, the perception of injustice in particular, combined with citizens’ faith in democracy, provided a strong motive to join the protests. The protests highlight the significance of political solidarity and citizens’ moral conviction for the need to defend a democracy in crisis (Subašić et al. 2008; Zomeren et al. 2011). Having witnessed an unprecedented corruption scandal featuring the president, Choi Soon-sil, and the conglomerate Samsung, Korean citizens perceived Korean democracy as under threat. Their conviction that it had to be saved functioned as an adhesive, uniting many participants from diverse backgrounds and giving them a shared identity beyond their narrow economic interests.

Third, the empirical analysis of this study also found the significant influence of this identity on participant efficacy. Without a strong sense of political efficacy, the protests could not have attracted and held together such a large number of participants. Participant efficacy can increase in several ways. In the case of the Korean Candlelight Protests of 2016–2017, in particular, the role of SNSes was hugely influential. There were at least five ways to join the Candlelight Protests via online media: use of hashtag for agenda setting, real-time social media for real-time information on the Candlelight Protests, mobile apps for communicating the location and useful information about the protests, community mapping for collective recording, and partaking in parody games for mocking and enjoyment.12 As more citizens became aware via SNSes of the increasing support for the protests, more citizens were motivated to join. Also, to be sure, the prevalent non-violence strategy of protests served to attract more participants.

Fourth, the role of emotion was also confirmed. In most of the rational approaches to collective action, emotions are often regarded as an error term. As this study shows, however, emotion—and anger in particular— should be considered more seriously in explaining the process and outcome of the protests.

The empirical analysis of this study was based on a unique dataset, which may constitute an asset. However, the limitations of that same dataset may have prevented the study from achieving better results. In any future analysis, consideration of the following aspects would be beneficial. First, shared identity could be constructed from the context, particularly relating to the repeated experience of protest participation. Thus, analysis of the effects of interaction among the participants in protests would be highly desirable. This study only partially touched on the role of emotion, with a focus on citizen anger. Any future analysis should examine the role