THE DEBATE ABOUT INTERDEPENDENCE AND CONFLICT

The liberal peace hypothesis has been considered as one of the most promising ideas to promote peace in international relations. Pursuing to build a universal and general theory, abundant previous research has extensively examined this hypothesis. According to the liberal hypothesis, the increase in bilateral trade is evaluated to further the security relations because the two countries are restricted from conflict behaviors due to the fear of the severance of trade relations. Immanuel Kant viewed that war was a natural phenomenon and peace was created by the will of people. He insisted that because the power of money, which is obtained through commerce, was the most dependable of all the powers, including military, states were ultimately forced to promote peace rather than war (Kant 1957).

While the liberal hypothesis has not entirely evolved to a unified theory, the majority of empirical studies support it. As a pioneer of quantitative analysis on the effects of trade on conflict,Polachek (1980) found that countries with the greatest levels of bilateral trade volume were involved in the least, and less intense, number of disputes. In addition, he also recognized that trade is an endogenous, predetermined variable. He found that causality still runs from trade to conflict even when accounting for simultaneity (

In addition to the debate about the theoretical concept of interdependence, Mark J. Gasiorowski started to open the debate about the measure of interdependence particularly in terms of cost-benefit analysis (Gasiorowski 1986). He noted that a country’s total trade ratio to its GDP is not an indicator of the costs of interdependence, but rather is only a measure of the benefits of interdependence. He suggested that the costs of interdependence are divided in two categories: vulnerability, which can be measured by a trade partner concentration index and the commodity concentration of exports, and sensitivity, which is measured by short- and long-term capital flows. The results of Gasiorowski’s statistical analysis showed that costly trade produces an increase in conflict, while beneficial trade produces a decline in conflict. Testing the realist hypothesis that foreign trade is one of the motives for war, William K. Domke found that high levels of exports are most significantly associated with lower levels of conflict (Domke 1988). Joanne Gowa and Edward D. Mansfield assumed that trade produces security externalities and found that allies trade more with each other than do non-allies under bipolarity, but that this relationship disappears under multipolar. The findings imply that trade gains would be utilized to enhance the military power of any country that engages in it (Gowa and Mansfield 1993). Edward D. Mansfield also presented evidence of a liberal hypothesis that international systems that were more open to foreign trade were less likely to engage in military disputes (Mansfield 1994). John R. Oneal, Frances H. Oneal, Zeev Maoz, and Bruce Russett first paid attention to the pacifying effects of trade between warprone dyads. Employing a politically relevant dataset and measuring economic interdependence with the ratio of bilateral trade to GDP, the authors found that trade was a powerful and positive influence for peace, especially among warprone contiguous pairs of states (Oneal, H. Oneal, Maoz, and Russett 1996).

Obviously, focusing on the Kantian ‘Triangulating Peace’ consisting of trade, democracy, and international organizations, Bruce M. Russett, John R. Oneal, and others represent the clearest statement of the liberal position, the significant empirical findings supporting liberal claims, and the most powerful defense against criticisms of the liberal hypothesis (Oneal and Russett 1997; Russett, Oneal, and Davis 1998). They adopted the weak-link assumption that the likelihood of conflict was primarily a function of the freedom for military action of the less-constrained state. That is, “the less dependent should have greater freedom to initiate conflict because its economic costs would be less and the beneficial influence of trade as communication would be less.”(Oneal and Russett 1997, 276) This is consistent with the idea that asymmetric trade relations can be a source of influence (Keohane and Nye 1989; Kroll 1993). Employing politically relevant dyads for the Cold War era, the authors measured economic interdependence while focusing specifically on the country with the lower bilateral tradeto- GDP ratio in the dyad. They found that the pacific benefits of interdependence were evident in all their tests. In the later research (Oneal and Russett 1999), Russett and Oneal expanded the period under analysis to 1885-1992 and employed all possible dyads instead of only those dyads that were politically relevant. As before, the operational index of interdependence was the measure of bilateral trade-to-GDP and the weak link dyad. The results of the analysis provide strong support for the pacifying influence of trade based on the weak-link assumption. Finally, using the entire 1885-1992 set of politically relevant dyads, they evaluated the effect of bilateral trade on conflict. The results of their logit regression analysis showed that interdependence significantly reduced the risks of dispute.6 The problem with the weak link measurement was its inability to determine whether the less constrained countries were actually initiators or whether they were not within a dyad in which conflict occurs. Recently, Zeev Maoz found that the liberal paradigm is consistently supported in the research.7

Unlike most liberals who attempted to build a universal theory, applying all actors in all times and places, Edward E. Mansfield and B. M. Pollins emphasized the importance of identifying the contingencies and boundary conditions of economic exchange on belligerence (Mansfield and Pollins 2001). First of all, the expansion of commerce is considered as one of the products of political and military struggles throughout history.8 In this context, some scholars have found that the interactions between interdependence and domestic coalitions (Solingen 1998) or state institutions (Papayoanou 1996) had influenced a state’s propensity to fight. Havard Hegre found that the relationship between trade and conflict was statistically significant only in dyads consisting of two developed countries, implying that the relationship was basically contingent on the level of development (Hegre 2000).

Particularly suggestive was work by Edward D. Mansfield and Jon C. Pevehouse analyzing the effects of bilateral trade flows and preferential trade arrangements (PTAs) on interstate disputes during the Cold War period. Their findings indicated that while trade linkages had little effect on the reduction of disputes between states that did not participate in the same PTA, those linkages have a strong, inverse effect within PTAs (Mansfield and Pevehouse 2000). Christopher F. Gelpi and Joseph M. Grieco found that democratic leaders are more averse than autocratic leaders to initiating military conflicts with trading partners because conflicts could damage commercial ties (Gelpi and Grieco 2008). The authors assumed that democratic leaders relied more heavily on public policy successes, particularly economic growth. Their findings implied that the pacifying effect of trade exchange depended upon the prior presence of democratic institutions of government.

The strongest challenges to the liberal proposition emerged with the introduction of a new operational index of interdependence which consisted of three dimensions: trade salience, symmetry, and their combined effect (Barbieri 1996;

In addition, developing new estimation techniques to correct statistical problems caused by duration dependence, Nathaniel Beck and his associates found that trade is not considerably associated with disputes.9 When controlling for temporal dependence, however, later research showed that higher levels of trade dependence dramatically reduced the odds of conflict, particularly among nondirected dyads (Bennett and Stam 2000).

In testing the liberal peace hypothesis, simultaneity has been one of the major issues. Accordingly, some scholars have found that there was a simultaneity problem in the relationship between interdependence and conflict (Reuveny and Kang 1998;

In sum, scientific research on the liberal peace hypothesis has made crucial progress over the last 30 years in terms of defining the causal mechanisms, measurement, model specification, and the use of advanced statistical techniques, although the applications of these new ideas still remain open to question. In addition, the majority of empirical studies have supported the core liberal claim. However, the liberal peace hypothesis has not evolved into a unified theory, as shown in the competing findings.

1In addition, this realist position was explicitly displayed in the issue of a nuclear DPRK as follows. One nuclear strategist, John Mearsheimer, said, “It might be the best choice for the ROK to be armed with its own nuclear deterrent against nuclear DPRK.” (Korea Joongang Daily 2013). 2Glaser (1992). See Coale (1985, 488). Coale noted that the United States and the Soviet Union didn’t directly engage in military disputes in East and West Europe during the Cold War. 3Sagan (1995) presented two reasons for the major impediments to pure rationality in organizational behavior: a severely bounded form of rationality inherent in large organizations and conflicting goals inherent in complex organizations. 4Ibid. Sagan argued that there were five strong reasons to expect that military officers are predisposed to view preventive war in particular in a much more favorable light than are civilian authorities:i) military officers seeing war as inevitable in the long run, ii) training to focus on pure military logic, iii) displaying strong biases favorable to offensive doctrines, iv) tending to plan for war, and v) narrowly focusing on their specific job. 5Ibid. For example, during both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, senior US military officers seriously advocated preventive war options against the Soviet and China and, in both cases, continued favoring such ideas well after civilian leaders ruled against them. In contrast, Waltz maintains that a nuclear state is not likely to initiate a preventive strike against a non-nuclear adversary because it would be hard for a nuclear state to destroy another country’s potential for future nuclear development (Waltz 1995, 18). 6Russett and Oneal’s (2001) major interest was in the democratic peace theory, so in this work one of their main goals was to analyze the combining effects of economic interdependence and democracy on military conflicts. 7Maoz divided interdependence in two types: economic and strategic. He assumed that whereas most liberals regarded both strategic and economic interdependence as a source of peace, realists expected strategic interdependence to reduce the likelihood of dyadic conflict (2009, 225-226). 8Mansfield and Pollins argued that “commerce has expanded during the past four centuries within two different policy contexts: initially embedded in a more state-directed and imperialist environment during the mercantilist era and later within a more liberal economic regime” (2001, 844). 9Beck, Katz, and Tucker’s (1998) logit model is based on an assumption of independent observations. However, when a militarized interstate dispute data set was utilized, this assumption was violated because of the dependence and rarity of events. To address these problems, the authors suggested the use of peace-years and three cubic splines variables from the BTSCS algorithm.

THE LIBERAL PEACE AND NUCLEAR ASYMMETRY

Largely ignored in the empirical research on the liberal peace hypothesis has been the pacifying effect of economic exchange within conflict-prone dyads such as what has been seen in situations of nuclear asymmetry as discussed in this paper. In that regard, particularly important is the research by John R. Oneal and his associates, indicating that higher levels of economic exchange inhibited disputes, especially between contiguous states (Oneal, H. Oneal, Maoz, and Russett 1996). In this study, the authors first showed that geographic proximity was the most powerful among all other variables to explain conflict. Then they evaluated the effect of trade on conflict only within contiguous pairs of states, where the potential for conflict was greatest, controlling for all other variables. The implications of these findings were quite straightforward: economic interdependence significantly counteracts the negative influences of the conflict-prone variable (

Nevertheless, previous empirical studies have paid little attention to the likelihood of cultivating trade relationships (liberal peace) between adversaries, previously hostile countries, enduring rivalries or conflict-prone dyads. Rather, some studies have proposed that economic relations were influenced by states’ security interests, as well as by economic concerns. That is, in addition to economic and material concerns, such as price and quality, the utility of importers and exporters is affected by the political and security concerns of managing risk, such as the desire to reward friends, punish adversary, and minimize the risk of economic disruption (Pollins 1989a; Pollins 1989b). Gowa and Mansfield (1993), and Gowa (1994) have shown that states are more apt to trade with allies than non-allies. They assumed that the economic gains arising from commercial relation were also the source of the security externalities that can either impede or facilitate it. A state tends to trade with an ally because the economic gains arising from commercial relations could be used to threaten its security, and allies ostensibly do not pose such security threats. In contrast, trade with an ally produces a positive externality. For example, from this point of view it could be argued that, after World War II, the United States deliberately opened its markets to Japan to facilitate Japan’s revival as a prosperous and democratic ally.

These ideas, however, can’t fully explain the best examples in favor of the liberal peace theory, such as the formation of the European Economic Community, Richard Nixon’s opening to China, Willy Brandt’s

If so, under what conditions would a liberal peace be likely in a situation of nuclear asymmetry, which clearly involves conflict-prone relations? In other words, why do states in nuclear asymmetry choose to enter trade alliances, thereby leading to a reduced probability of conflict? The previous empirical research on alliance formation shows that countries tend to select allies that are opposite to them in asymmetry in power (Altfeld 1984; Morrow 1991) or regime types (Simon and Gartzke 1996). Altfeld (1984) has mainly argued that alliance formation is the product of trade-offs between security and autonomy, and between armaments and welfare, as shown in the linear budget constraint for most economists. This implies that the majority of alliances are very asymmetric, showing a combination of a major and several minor powers rather than collections of powerful nations alone. Morrow (1991) has also found that asymmetric alliances in size and capabilities are easier to form and last longer than symmetric alliances because each side receives different benefits. In asymmetric alliances, the stronger partner gains autonomy and provides security to the lesser partner (930). He found that the majority of alliances are asymmetric during his period under analysis. Simon and Gartzke assumed the bias of politically dissimilar states in favor of selecting each other as alliance partner was because partners may receive something like gains from trade to offer each other beyond security aggregation (Simon and Gartzke 1996). Furthermore, “politically asymmetric alliances have the advantage of combining the complementary qualities of democratic and autocratic partners” (

In the liberal position, these findings of asymmetric alliance formation were applied in the research on the pacifying effects of economic linkages in large and small countries by Polachek, Robst, and Chang (1999). Their main argument was that trade linkages in situations involving asymmetry in economy size led to decreased conflict. Along with the findings of asymmetric alliance formation in power asymmetry, the authors assumed that small countries have an incentive to join trade alliances with large countries due to the security that a large country can offer. Theoretically, in addition to this security gain from trade with large countries, small countries have markedly more gains in such areas as domestic consumption and an increase in investment. In short, the authors assumed that large countries entered into trade linkages with small countries to receive trade gains, while small countries entered into trade relations with large countries to gain security. Accordingly, when being conflictual with a large trading partner, small countries are more restricted in terms of conflict escalation because they could lose security as well as trade gains. They found that a small country increasing trade with a large target reduced conflict more than a small country increasing trade with a small target.

A serious question in Polachek, Robst, and Chang’s empirical test was the operational index of the large and small countries with the differences in GDP size. Are large countries, as measured by the size of their GDP, substantially capable of offering security to their relatively smaller trading partners? While it could be true that the United States was capable of providing reliable security to the Republic of Taiwan, it would be hard to believe that Japan would be capable of such provision to Taiwan. Hence, size asymmetry in economies would not capture those cases where trade ties lead to greater security.

Here, employing the concept of security gains generated in asymmetric relations in power (Altfeld 1984; Morrow 1991), regime type (Simon and Gartzke 1996), or economy size (Polachek, Robst, and Chang 1999), I further develop the idea of a pacifying effect of interdependence in situations of nuclear asymmetry. I assume that states in nuclear asymmetry prefer each other as trading partner because each partner receives different benefits. In addition, economic linkages in nuclear asymmetry could generate two mutually exchangeable benefits: security gains for non-nuclear states and trade gains for nuclear states. Economic exchanges in nuclear asymmetry could lead non-nuclear states to gain the security benefits that nuclear states can offer. While nuclear states cannot get security gains, they could still get trade gains. When nuclear and non-nuclear states engage in disputes, both states lose security and/or trade gains. Non-nuclear states, of course, are relatively more restricted from the conflict with nuclear trading partner because conflicts could damage commercial gains as well as security gains for the non-nuclear states. Accordingly, I argue that trade linkages in nuclear asymmetry are more likely to reduce conflict than nuclear symmetry. Ultimately, the pacifying effect of interdependence in nuclear asymmetry is more significant than any other dyads.

I assume that a non-nuclear state enters into trade alliance with a nuclear state to obtain security that the nuclear state is capable of offering. Accordingly, the more nuclear states it moves into trade linkages with, the more advantageous security gains the non-nuclear state could acquire. To maximize its security, a non-nuclear state could attempt to form trade alliances with more nuclear states, practically with all the nuclear states in the international system. In addition to security gains, a non-nuclear state could take either trade gains from its larger nuclear trading partner or economic leverage to pressure its smaller nuclear trading partner. If a non-nuclear state is larger than its nuclear trade partner in size, a non-nuclear state would willingly enter into economic relations with the nuclear state because that economic relationship would provide a non-nuclear state with economic leverage to pressure the nuclear state in the short term, as well as security gains in the long term. In the long term, the non-nuclear state could expect to achieve security gains that its nuclear trading partner can offer. If a nonnuclear state is smaller than its nuclear trading partner in size, the non-nuclear state willingly gets into economic ties with a larger nuclear state because the smaller non-nuclear state could obtain economic gains in the short run, as well as security in the long run. “An increase in the price of exports could have relatively more considerable direct impact on the domestic economy of a small rather than that of a large” non-nuclear state (

I further assume that a nuclear state enters into trade linkages with a nonnuclear state to obtain trade gains. Nowadays most states tend to comply with the rules of the international trade regime. In order to nurture its own wealth, power, and welfare, a state has essentially two options: increase international trade or pursue territorial expansion (Rosecrance 1986). For example, since WWII Japan has converted from a strategy of military invasion to one of trade promotion as a means to achieve wealth (Mueller 2009). “Nowadays Japan would aim at the military invasion to obtain raw materials and petroleum if it were in 1930s, but it uses international trade.” (

Consequently, it is contended that trade linkages in situations of nuclear asymmetry reduce conflict more than trade in situations involving nuclear symmetry. Ultimately, the pacifying effect of international interdependence in the nuclear asymmetry would be more significant than any other dyads.

Accordingly, the pacifying effects in situations of nuclear asymmetry could be hypothesized as follows:

To capture any negative evidence for the liberal hypothesis in nuclear asymmetry, I also construct and examine a rival hypothesis that the expansion of trade linkages in nuclear symmetry is less likely to inhibit conflict. That is, I assume that the intensive and extensive economic ties in a trade partnership involving countries in a situation of nuclear symmetry (either both countries have nuclear weapons or neither does) could not generate special incentives such as security gains. Hence, there would be no significant effect in decreasing the likelihood of dyadic disputes between them. A rival hypothesis has been constructed as follows:

H2 : Economic interdependence in a situation of nuclear symmetry is less likely to lead to reduced conflict.

10Barbieri and Levy (2001) statistical analysis showed that in most cases war does not have a significant impact on trading relationships, rejecting the realist position that concerns about security externalities lead to a reduction or elimination of trade between enemies.

The primary goal of this research is to quantitatively examine whether economic interdependence in nuclear asymmetry is associated with disputes. The unit of analysis is dyad/year and the period under analysis is 1950-2001, which is based on the accessibility of data.11 To test hypotheses, a cross-sectional pooled time series data set is established. In addition, I employ all dyadic samples rather than using only politically relevant samples. A recent study found that politically relevant samples significantly bias the results of the statistical analysis on the relationship between interdependence and conflict.12 The Eugene Expected Utility Generation and Management Program is utilized to construct the directed dyadyear data (Bennett and Stam 2000). In tmy research model, the dependent variable is the onset of militarized interstate disputes (MIDs). The independent variable is economic interdependence, which is operationalized along three dimensions of trade: i) trade salience, ii) trade symmetry, and iii) interdependence, which addresses their interaction terms. Control variables consist of i) dyad size, ii) proximity, iii) regime type, iv) relative capability, v) military alliance, and vii) post-Cold War. Accordingly, the model that will be tested below is summarized in the equation:

Dependent variable: Onset of militarized interstate disputes The dependent variable is the outbreak of militarized interstate disputes, which involves the initiation of disputes. The dataset of the dependent variable is derived from the Dyadic Militarized Interstate Disputes (MID) Data of the Correlates of War Project.13 Accordingly, ongoing disputes are excluded from the MID dataset. The dependent variable is dichotomous. When any one of threat, display, use of force, or war occurs (Jones, Bremer, and Singer 1996), it is coded as 1, otherwise 0.

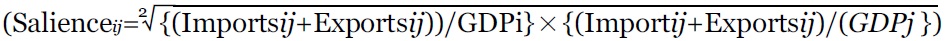

Independent variable: Economic interdependence Economic exchange is measured by bilateral trade volume. The operational indices of economic interdependence are three dimensions of trade: salience, symmetry, and their interaction term, as suggested by Barbieri (Katherine Barbieri 1996; 2002). The trade data is transformed with the Expanded Trade Data suggested by Kristian Skrede Gleditsch (Gleditsch 2002), which could considerably reduce the missing data for the Communist countries just after WWII.

Trade salience Trade dependence of State i on j is measured by using the trade share of total bilateral trade with State

The value of trade salience ranges from 0 to 1. If it is closer to 1, it could be interpreted that the importance of economic relations in the dyad is high, otherwise low.

Trade symmetry Barbieri hypothesizes that conflict is less likely between states with symmetrically dependent trade linkages. Trade symmetry is 1 minus the absolute value of the difference in trade salience

Interdependence This operational index is the interaction terms of trade salience and symmetry. In general, interaction terms could imply high multicollinearity. Hence, an attempt is made to reduce the expected multicollinearity by multiplying the standardized trade salience and symmetry (Friedrich 1982). In principle, this value would be higher when both trade salience and symmetry are high. If either the trade salience or symmetry is zero, or closer to zero, the trade linkage in a dyad could be interpreted as unilateral subjective relations. In theory, the concept of trade symmetry and the interaction term of trade salience and symmetry are not suggested in the liberalism.

Nuclear states The data on nuclear states were collected based on the guidelines suggested by Erik Gartzke and Matthew Kroenig (2009), and Gartzke and Dong-Joon Jo (2007). According to those authors, for a state to be judge ‘nuclear’ requires both nuclear development programs and a substantial number of nuclear warheads. Accordingly, the Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus in 1992 are not coded as nuclear states because those countries didn’t have viable nuclear development programs.14 In general, conceptually it is not controversial that the five major powers are identified as nuclear states. Some countries, however, are controversial in identifying when the starting or ending date for the possession of nuclear weapons was. First, for countries that are assumed to possess nuclear weapons in secret, the starting date of possession is defined by the year when the possession of nuclear weapons was confirmed by related documents. Second, the end date of the possession of nuclear weapons was defined by the year when the supreme decision-maker completely dismantled those nuclear weapons. According to these criteria, 10 countries having nuclear capabilities are identified as ‘nuclear states’: the US from 1945, Russia from 1949, the U.K. from 1952, France since 1960, China from 1964, Israel from 1966, South Africa between 1979 and 1991, India from 1988, Pakistan from 1988, and the DPRK since 2006. This variable is dichotomous; when any state is identified as a nuclear state, it is coded as 1, otherwise 0.

Dyadic size Many previous studies have found that gross domestic product correlates significantly with conflict (Benson 2005; Hegre 2004; Mansfield and Pevehouse 2000; and Gasiorowski 1986). Accordingly, the effect of this variable is controlled in the model. This variable is operationalized by the sum of the GDP of the two countries in a dyad.

Contiguity If two countries in a dyad share common borders or are less than 400 miles away, they are defined as proximate and coded as 1, otherwise 0. Geographical contiguity has been found significant in increasing the likelihood of disputes (Hegre, Oneal and Russett 2010; Oneal, Maoz, and Russett 1996; Bremer 1992; Siverson, and Starr 1991; Starr and Most 1976).

Joint democracy It has been demonstrated that disputes are less likely between countries with high joint levels of democracy(Bennett and Stam 2004; Maoz and Russett 1993; Dixon 1994; and Bremer 1992). In particular, comparative analysis of international relations shows that conflict between democratic political systems is minimal (Bennett and Stam 2004, 24). The joint level of democracy is measured using the Polity IV Data (Joint Democracy

Relative capabilities Most previous conflict studies control for the variable of relative power (Kugler and Lemke 1996; Bremer 1992; Mesquita and Lalman 1992; and Organski and Kugler 1980). On the contrary to the expectations of balance of power theory, most research has found disputes less likely in dyads with more asymmetric power relations. The capability data is taken from the natural log of the sum of the capabilities of the two countries in a dyad which are derived from the COW Composite Indicator of National Capabilities Index.16

Post-Cold War While the number of disputes varies by time and across regions since the end of the Cold War, it could generally be considered as a declining pattern. It was reported that during the 1990-1997 period after the Cold War, interstate wars significantly declined compared to the previous 10-year period (Sarkees, Wayman, and Singer 2003). The post-Cold War period is coded as 1, otherwise 0.

11So far, the most recent data for MIDs, which is the dependent variable in this paper, is just available up to 2001 when we utilize the Eugene Expected Utility Generation and Management Program in order to construct data specified for this research. 12Benson (2005) examined the effects of politically relevant dyads on the relationship between trade linkages and conflict. In fact, a politically relevant sample includes at least one major power by 70% and at least one very large economy to an abnormally high proportion (Ibid., 117). She found that politically relevant dyads are significantly biased toward major powers, always showing a negative, significant effect of salient trade on disputes (Ibid., 130). 13Available at

Logit regression analysis is used because the dependent variable is the onset of disputes. In general, there are two problems in applying the logit statistical model to analyze interstate militarized disputes. One of most important assumptions of the logit statistical model is the independence of events. This assumption, however, could be easily violated because disputes could, by their nature, have a strong impact either on one another or follow-up disputes. The other problem is that the onset of disputes is relatively quite rare. To address these problems, the duration dependence technique suggested by Beck, Katz and Tucker (1998) is employed through the use of the variable peace-years and three cubic splines variables from the BTSCS algorithm. The logit model is nonlinear, so no single method of interpretation can lead us to fully describe the relationship between a variable and the outcome. I present the factor change in the odds as shown in Table 1.17

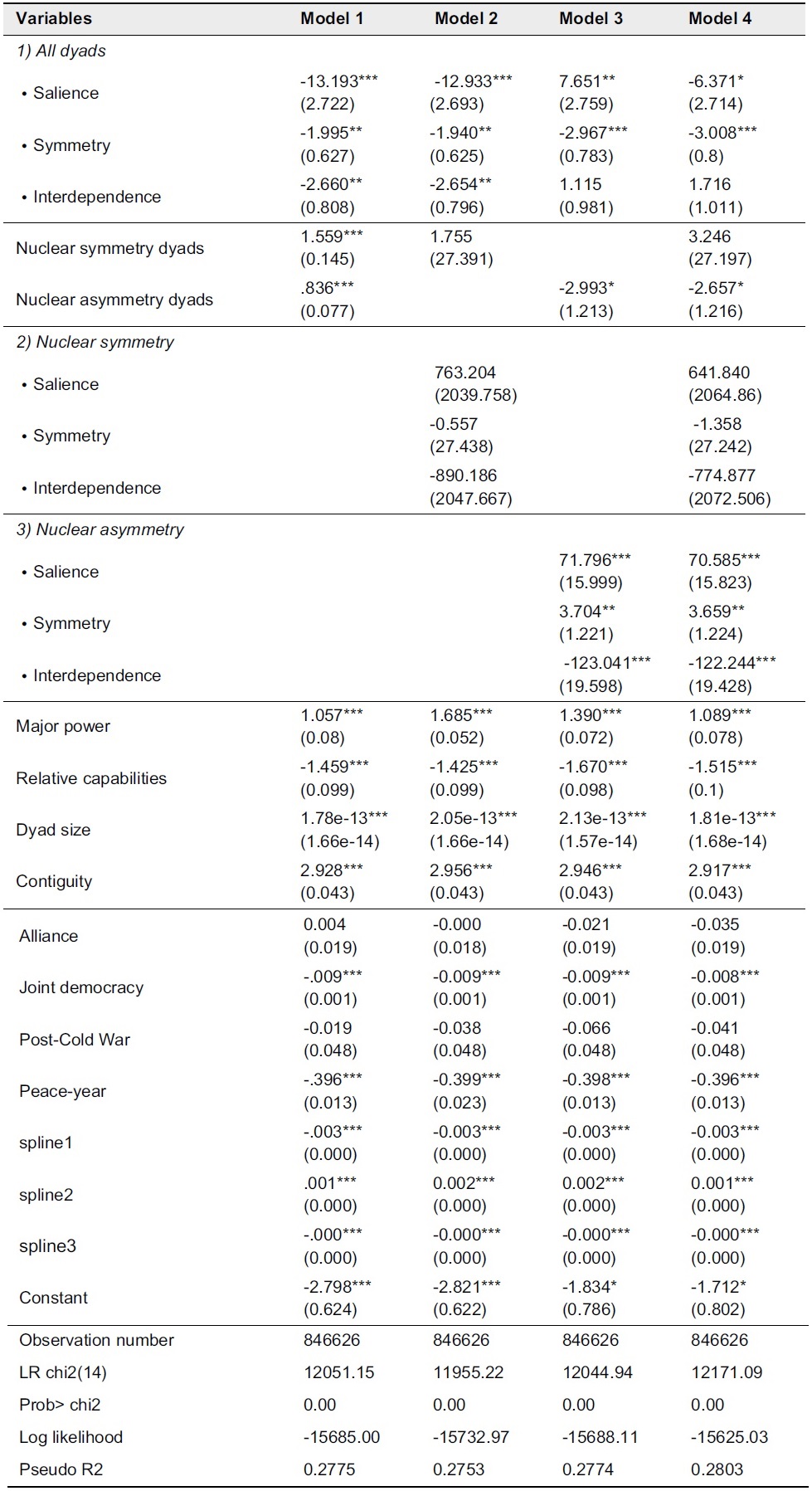

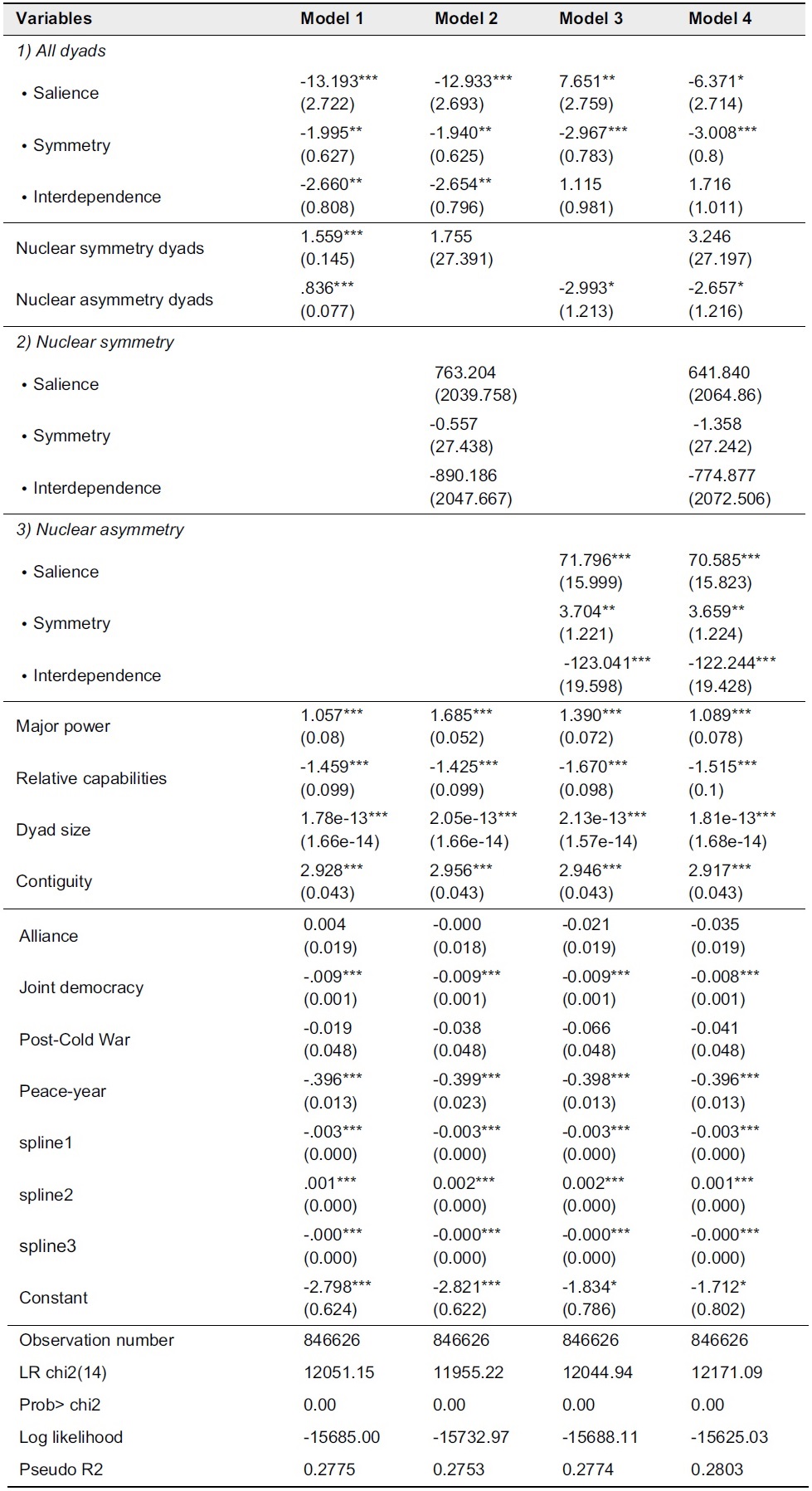

[Table 1.] Duration Dependent Logits and Onset of Dyadic Disputes: 1950-2001

Duration Dependent Logits and Onset of Dyadic Disputes: 1950-2001

In order to examine whether the distinctions of economic ties in

Overall, the results of the statistical analysis show that economic linkages in situations of

Firstly and most importantly, Model 4 addresses the primary research question of whether trade linkages in

Particularly, in

In contrast to the liberal argument, as shown in Model 4, symmetrical trade ties in

Surprisingly, Model 4 shows that in

As shown in Model 4, in nuclear symmetry, the coefficients for

As shown in Model 1, in strong support of the liberal hypothesis, economic relations in

As expected in the rival hypothesis, Model 2 reveals that the pacifying effects of economic interdependence in

The results from Model 3 reveal that all three dimensions of trade relations in

The findings from the control variables offer few surprises. Dyads with one major power are more likely to engage in militarized disputes. Dyads with greater disparities of power are more likely to engage in disputes. Larger dyad size and contiguity are positively associated with the likelihood of dyadic disputes. The presence of an alliance has no statistically significant effect on the probability that dyads will engage in conflict. Disputes between democratic states are less likely. The end of the Cold War has no statistically significant effect on dispute likelihood.

In sum, in situations of

One last question concerns how to interpret the meaning of the coefficients for the addictive effects of

Also, the statistically significant and reverse sign of

Appendix A examines the question of whether higher levels of either

These findings from Appendix A are then integrated into those regarding

17In general, there are two methods of interpreting the results of the logit analysis, either as a discrete change in the probabilities or as a factor change in the odds (Long 1997, 151). These two methods are complementary. The change in probability is a useful way to assess the magnitudes of effects in the logit model. Yet, measures of discrete change do not indicate the dynamics among the dependent outcomes (Ibid., 168). The factor change in the odds can answer the question of the dynamics among the dependent outcomes. Of course, the interpretation of each odds ratio is quite simple (Ibid., 168-169). The reason why I do not present the change in the probability is that it is quite complicated to calculate the change in the probability on the combining effect of trade salience and symmetry.

This paper mainly aimed to address the question of whether a liberal peace is likely in

Along with these assumptions, I constructed a primary liberal hypothesis with respect to

Is a liberal peace likely in situations of

The theoretical implications of these findings are quite significant and straightforward, further challenging the realist claims that economic interdependence has minimal systematic influence on conflict. Furthermore, economic relations substantially dampen hostilities in conflict-prone states as shown in situations of nuclear asymmetry, which reflects the extreme vulnerability of relations in the current international system. In addition, these findings are consistent with those in previous research (Oneal, H. Oneal, Maoz, and Russett 1996). In sum, this paper clearly demonstrates the utility of the liberal peace claim, particularly in relations between conflict-prone states.

These findings have significant practical implications particularly for such nuclear asymmetric relations as those between the two Koreas. In the nuclear era, the sad truth is that an absolute majority of countries have no option but to live with nuclear states. Obviously, peace is not given, but rather is created by the will of people. The findings reveal that, while countries in situations of

The findings presented here have several important theoretical implications for future research on the study of trade and conflict in situations of