LITERATURE REVIEW: PERSPECTIVES ON ANTI-IMMIGRATION PARTIES AND SWEDEN

>

DEMAND-SIDE PERSPECTIVES AND SWEDISH EXCEPTIONALITY

The question of why no radical right anti-immigration party emerged on the national political scene in Sweden generated a great deal of research roughly divided into two categories, demand-side and supply-side theories. Many dominant demand-side theories stated that the persistently high salience of the economic cleavages, and the correspondingly low prominence of new socio-cultural cleavage, worked against the emergence of a strong radical right anti-immigration party in Sweden (Rydgren 2002; Benoit and Laver 2006; Rydgren 2010). Demand-side theories built their major contention on earlier findings that traced the emergence of radical right anti-immigration parties largely due to the growing salience of new socio-cultural cleavages. For instance, some researchers contended that radical right anti-immigration parties arose as a consequence of a profound transformation in the socioeconomic and socio-cultural structure of advanced capitalist post-industrial democracies (Betz 1994; Kitschelt 1995; Taggart 1995; Kriesi et al. 2006).

Seen from this demand-side perspective, economic concerns persistently dominated the Swedish political scene and rendered little leverage to radical right parties that emphasized cultural protectionism, xenophobic welfare chauvinism, and anti-establishment populism. In other words, the Swedish Democrats could not fully mobilize and rally voters behind an anti-immigration platform, primarily because the Swedish Democrats could not persuade the electorate that the immigration issue by itself posed a bigger burden to society than practical economic concerns over employment.

>

SUPPLY-SIDE PERSPECTIVES AND SWEDISH ABNORMALITY

While demand-side perspectives on anti-immigration parties in Sweden stressed the Swedish exceptionality, the supply-side perspective focused on Swedish abnormality. Typically, supply-side perspectives highlighted the established parties’ strategic behavior regarding the immigration policy agenda, namely the ‘dismissive issue strategy’ (Bale 2003). Since the late 1980s, public opinion has continued to be polarized by open immigration in many Western European countries. Some researchers contended that mainstream parties, in response to such a shift in circumstances, either took a firmer position on immigration or co-opted that of emerging anti-immigration parties (Meguid 2005; Arzheimer and Carter 2006). Sweden was no exception, in that such a swing in public mood consequently increased the salience and level of politicization of the immigration issue. Since the 1980s, Sweden Democrats also gradually gathered support at the local level by promulgating opposition to refugees in to Sweden.

In contrast to other Western European countries, however, Sweden’s mainstream parties at the national level jointly, and consistently, agreed not to invoke or exploit the immigration issue (Green-Pedersen and Odmalm 2008; Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup 2008; Dahlström and Esaiasson 2009; Rydgren 2010). 4 Odmalm (2011) even argued that the electoral marginalization of the Sweden Democrats largely stemmed from a low degree of politicization of the immigration issue among the parties. From this supply-side perspective on anti-immigration parties, the Sweden Democrats, despite the 2014 electoral surge to become the third-largest party in parliament, refused to cooperate over budget cuts on immigration and brought Sweden close to the brink of a snap election for the first time since 1958 precisely because other parties managed to secure a united front on immigration policy. In short, supply-side theories often stressed a low degree of issue politicization and the role of mainstream parties to foster such limited issuepoliticization.

Yet another thread in the supply-side theory is focused on the degree of convergence in policy positions between the established parties, actual or perceived. Supply-side theorists argued that, as the distance in political ideology gets smaller between the main parties, a potentially available niche for newly emerging parties occupying extreme positions on the ideological spectrum grows larger. This, in turn, can also affect demand-side factors in the political sphere, specifically the level of popular disaffection and discontent among the voters with the established parties or political elites (Kitschelt 1995; Van der Brug et al. 2005; Arzheimer and Carter 2006). Others noted that such popular disaffection and discontent did not mechanically lead to an “expansion in political opportunities” in Sweden contributing to the emergence of a new radical party with an anti-immigration emphasis, solely because of the low convergence between the mainstream parties, both actual and perceived (Rydgren 2002, 47; Oscarsson and Holmberg 2008).

>

PARTY-CENTRIC OR INTERNAL SUPPLY-SIDE PERSPECTIVE ON THE SWEDISH ATYPICALITY

We contend that both demand-side and supply-side factors are not sufficient enough to account for a sharp increase in the electoral fortunes of the Sweden Democrats since 2006 because both merely focus on the question of why Sweden remains an unsuccessful case. Indeed, Sweden is not a typical case. Supply-side factors, such as the mainstream parties’ dismissive strategies, and demand-side counterparts, such as the persisting prominence of economic cleavages in the Swedish political scene, remain simultaneously intact.5 To account for this recent transformation, we contend that an entirely different perspective on anti-immigration parties is needed. And, we do not have far to look.

We propose bringing anti-immigration party itself back to the central focus of research. Surprisingly little attention has been paid to party-centric or internal supply-side factors, such as party leadership, party organization, party propaganda strategy, or the party’s policy program, in accounting for the electoral performance of the Sweden Democrats (Carter 2005; Lubbers et al. 2002; Rydgren 2005; Mudde 2007). As Mudde (2007, 256) states, “irrespective of how favorable the breeding ground and the political opportunity structure might be to new political parties, [...] in the end, it is still up to the populist radical right parties to profit from them [...]. In other words, the party itself should be included as a major factor in explaining its electoral success and failure.” After criticizing previous studies that have ignored or undermined the role of the party itself in its own development, Mudde argues for making anti-immigration parties a component of independent variables, thus redirecting more attention to the demand side of the political sphere.

After all, even if favorable electoral support and an open political opportunity structure already exist in the public space, an anti-immigration party must reach out to be perceived to be a valid political option. In order to take advantage of such propitious opportunities, then, a successful anti-immigration party must equip itself with competent personnel, organization, a viable political program, and convince the electorate to regard it as legitimate and acceptable. Unfortunately, several scholars simply attribute this recent change in the electoral performance of the Sweden Democrats to causes external to the party, while stopping short of examining the party itself (Rydgren 2011; Dahlström and Sundell 2012).

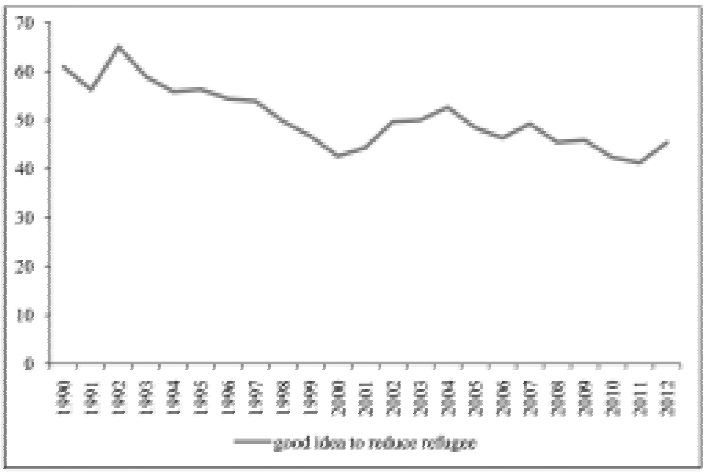

We need to take heed of party characteristics in order to understand party transformation, or lack thereof, in the Swedish political sphere. This is especially true since Sweden has had about as many citizens who were skeptical of the country’s open immigration and refugee policies as people in any other Western European country. As shown in Figure 1, there always existed a sufficiently large portion of voters holding negative views toward Sweden’s open immigration policy. Such public opinion on refugees briefly translated into political behavior in 1991 when New Democracy had its electoral breakthrough. This indicates that a niche in the electoral arena, defined as “gaps between the voters’ location in the political space and the perceived position of the [established] parties,” existed in Sweden, which held the potential to turn out advantageously for anti-immigration parties (Rydgren 2005, 418). Even though the mainstream parties did not abandon their open immigration principles and collectively continued to keep the immigration issue depoliticized, this niche remained latent for an anti-immigration party to convert into substantial electoral support.6 Swedish voters started to vote for the Sweden Democrats only after the party appeared on the political scene as an acceptable and sufficiently legitimate party by displaying, at least ostensibly, conformity to democracy.

We agree with Widfeldt’s contention that a challenger party can break in to an existing party system only if the extant party system “not only needs sufficient demand for the newcomer; but it also needs to supply a package that can meet that demand” (Widfeldt 2008, 265). This is particularly pertinent today for some anti-immigration parties occupying the European political space, including the Sweden Democrats, since they originated from a traditional right-wing extremist tradition, such as fascism or neo-Nazism. Mainly because of their problematic origins and ties to extremism, these parties are ostracized as political pariahs and remain marginalized until they have been able to prove themselves otherwise to voters. That is, they have needed to break with such an extremist image and gain a more respectable position in order to garner recognition as a legitimate political alternative in a society that values democracy and renounces extremism, including racism, Nazism, and other similar political and individual attitudes.

It should be noted, however, that we do not overemphasize party-centric factors at the expense of other factors cited in previous works. We propose that an internal supply-side theory should supplement a more comprehensive and integrated account of the electoral performance of radical right anti-immigration parties. Indeed, we strive to address the scholarly inattention in previous works to internal supply-side factors when accounting for the electoral breakthrough of the Sweden Democrats. Specifically, we would like to explore and to test the hypotheses that the party’s various efforts toward ‘normalization’ or legitimization have been of critical importance in increasing electoral appeal to that portion of the electorate who has been skeptical about open immigration and attentive to immigration as an important political issue.

In the remainder of this paper, we will first provide a brief overview of the political development of the Sweden Democrats. While tracing their normalization process, this paper will highlight the leadership factor, especially the contribution of their third and incumbent leader, Jimmie Åkesson. We will also discuss the modification of the political program by analyzing the party’s manifesto. Then, we will test hypotheses in order to substantiate our version of an internal supplyside theory.

1As of 2012, about one-fifth of Sweden’s population is of a foreign background; specifically, citizens are either foreign-born or Swedish-born with two immigrant parents. 2See Figure 1 below. 3The Sweden Democrats was founded in 1988 and often has been labelled a far-right anti-immigration party. 4In 2008, for example, the bourgeoisie government of the Liberal Party (FP), the Moderate Party (M), the Centre Party (CP), and the Christian Democratic Party (Kd) successfully negotiated an interbloc deal with the Green Party (MP) which jointly formed the so-called ‘red-green’ party bloc with the Social Democratic Party (SAP) to further immigration policy liberalization. The Social Democrats and the Left Party which held a slightly more hardline position on restricting immigration than the rest, however, did not participate in this inter-bloc deal, yet also did not openly oppose it, either. 5Please refer to Appendix 1 for important issues raised during elections by political parties from 1979 through 2010. 6The Sweden Democrats could not assert their alternative to the official immigration policy, even though there was a considerable demand from a substantial minority of Swedes discontented with open immigration.

THE ‘NORMALIZATION’ PROCESS OF THE SWEDEN DEMOCRATS

The concept of ‘normalization’ is synonymous to that of ‘sanitization’ of a party’s sullied image, or the ‘de-radicalization’ or ‘moderation’ of its rhetoric and political messages to make them less radical and provocative. It also signifies ‘legitimization’ so as to eliminate the stigma of neo-Nazi and racist labels. In short, ‘normalization’ refers to endeavors aimed at escaping social ostracism and overcoming electoral marginalization by the party reorganizing itself in order to gain acceptance as democratic, ‘normal,’ and admissibly moderate and perhaps less radical, rather than be cast as a minor racist and/or neo-Nazi group, one that can hardly be entrusted with political representation.

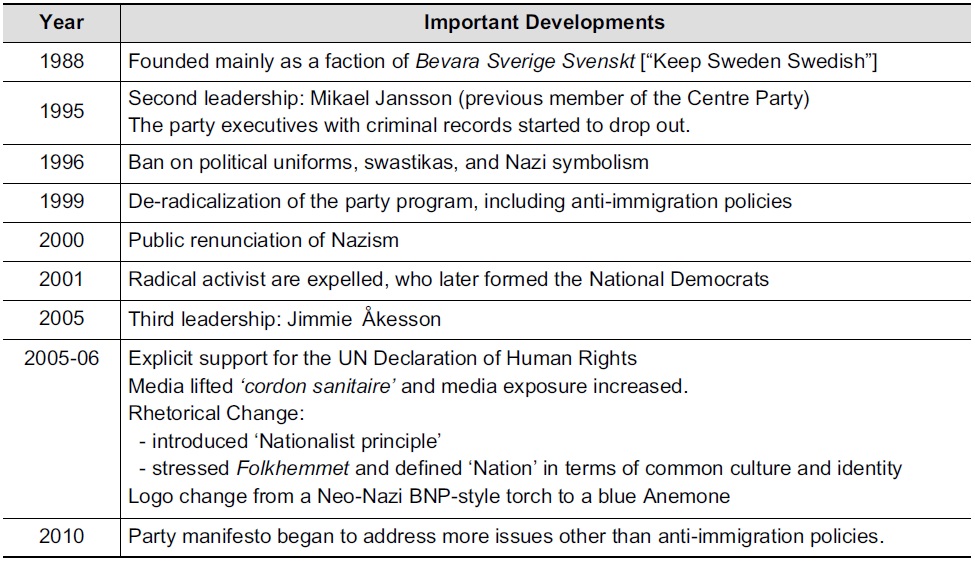

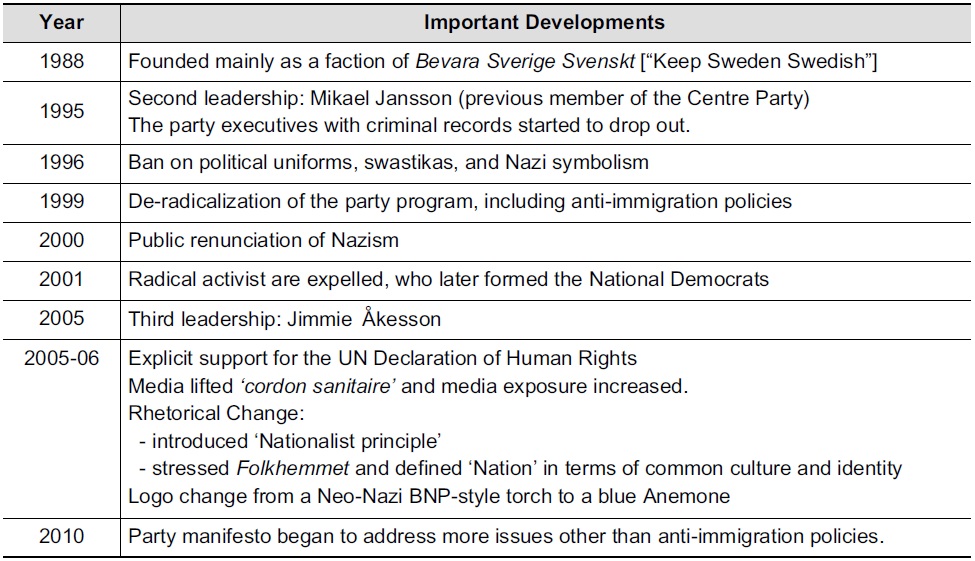

We argue that it was the origin of the Sweden Democrats that inevitably made the party dedicated to seeking the needed normalizing or sanitizing of the party image and past. The historical background of the Sweden Democrats is different from that of other anti-immigration parties in Scandinavia in that its roots lay in racism and neo-Nazism rather than social movements critical of heavy taxes and bureaucracy (Wodak et al. 2013, 277).7 Accordingly, we contend that it took rather a long time for the Sweden Democrats to dissociate themselves from their past as a racist group with links to fascist and neo-Nazi ideology, finally to freeing the party from the ‘stigma’ and its consequent marginalization on the political scene. To put it differently, we propose that the anti-immigration party of Sweden Democrats was able to make an electoral breakthrough only after 2006 when it succeeded in this process of normalization, as seen in Table 1.

[Table 1.] Sweden Democrats toward ‘Normalization’

Sweden Democrats toward ‘Normalization’

Origins matter because the remnants of the past tend to linger and political development is path-dependent. All things being equal, anti-immigration parties with extremist roots have a greater challenge to compromise because they are confronted with both the need to please loyal extreme activists while also urging a de-radicalization of its rhetoric in order to attract more moderate voters. Furthermore, marginal anti-immigration parties with restricted or limited media exposure and governmental party subsidies must rely on loyal activists who can deliver a political narrative to the electorate. The media boycotted the Sweden Democrats until 2006, so they were torn between the need to satisfy the preferences of extremists and the party’s desire to enlarge their electoral base (Rydgren 2005, 431-432).

Prior to 2006, the Sweden Democrats tried to cleanse the party image but to no avail. By placing Mikael Jansson, formerly a local politician for the Centre Party who had no criminal record, as the party’s second leader in 1995, the Sweden Democrats attempted to steer clear of their racial and fascist character as the newly-elected leader “presented the party with the clean image it so badly needed” (Widfeldt 2008, 269). Mikael Jansson banned uniforms and visible symbols of Nazism and paved the way to initiate party reforms.8 Yet he was neither a charismatic leader nor a potent speaker, lacking in assertiveness to push for changing the party symbol that was alarmingly similar to that of the neo-Nazi British National Party (Larsson and Ekman 2001, 170). He even advocated for a senior party executive with a criminal record (Expo 2010).

The Sweden Democrats also recruited Sten Andersson, a sitting member of parliament and of the Moderate Party, and witnessed a sharp increase in votes at the municipal level in 2002. However, the Sweden Democrats suffered several setbacks, including the backlash from racist remarks of their city council members and defection of a high-ranking party executive (Expo 2010). Consequently, the impact of enlisting Andersson was rather small, as the party had disappointing performances in the euro referendum and the EU election in 2003 and 2004, respectively (Widfeldt 2008, 271).

Then in May 2005, Jansson lost his position to the then-26-year-old Jimmie Åkesson,9 partly due to factional infighting. The so-called “bunker group” of traditionalists supported Jansson who, in turn, chose to stay tolerant of remaining radicalism in the party. Meanwhile, Åkesson insisted on accelerating the modernization process by strengthening the party organization (Widfeldt 2008, 271).10 He also embraced moderate revision of the party program in 1999, “a giant step forward for the party” to better align with political realities, by calling for changes in the immigration policy agenda that previously demanded the enforced repatriation of all immigrants who had entered Sweden since 1970 (Wodak et al. 2013, 279-280).

It was not until Jimmie Åkesson was chosen as the third leader of the party in 2005 that the Sweden Democrats were finally able to relinquish their tarnished legacy and its overshadowing electoral marginalization. It was also after Åkesson came to power that the party symbol was changed from one reminiscent of its neo-Nazi connection to an innocent Anemone flower with Sweden’s national flag colors. Consequently, the Sweden Democrats managed to raise nearly 10 million Kronor for the election and doubled their votes in the 2006 national election despite having been unable to run any political advertisements in newspapers due to the still-standing media boycott and lack of public subsidies (Expo 2010). Åkesson successfully raised the party’s profile and visibility to the public by presenting the party with a respectable and professional image, while toning down the racist extremism from the party’s manifesto.11 Indeed, Åkesson became an icon of the party.

As the Sweden Democrats have continued to gain popularity, the daily newspapers

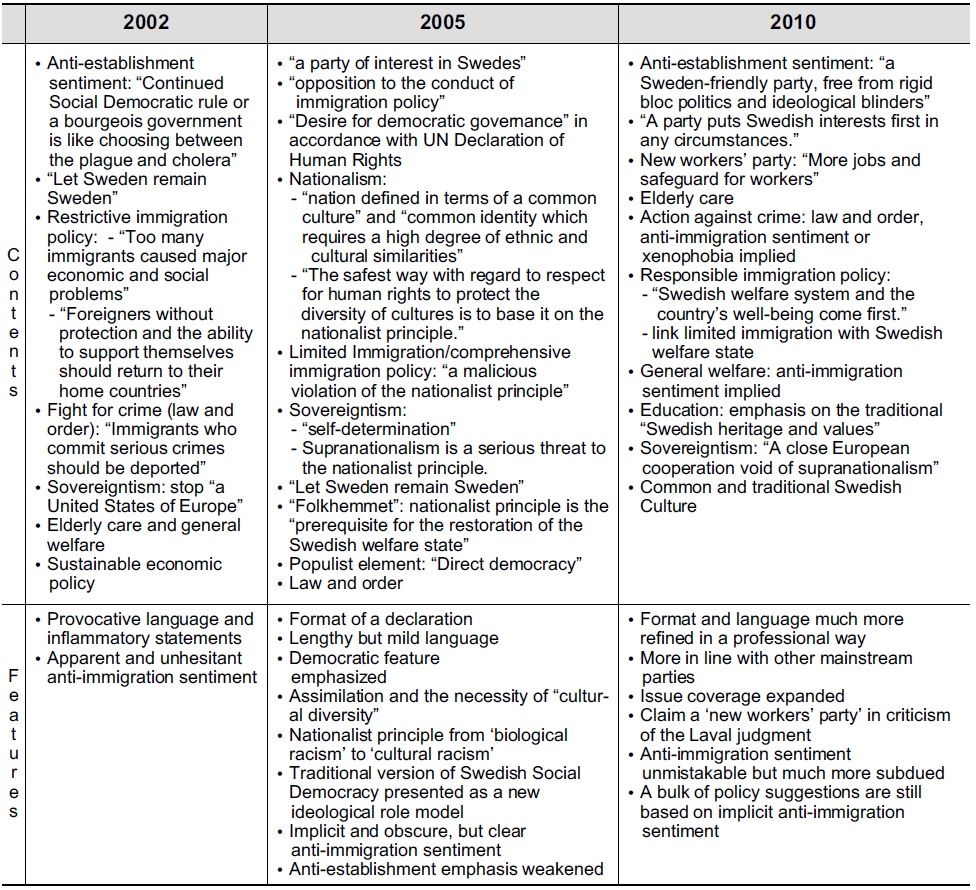

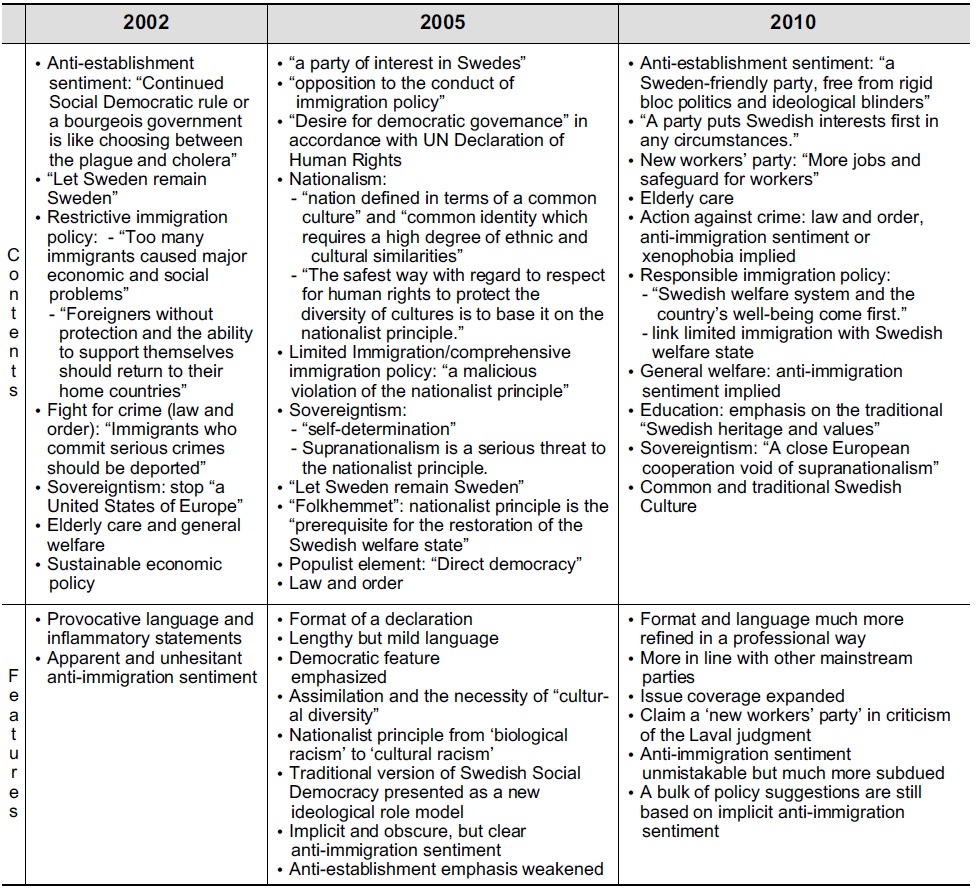

The party manifesto revealed an effort by party leadership and its rank and file members to reach out beyond its traditional base. In an effort to transform its party along more moderate lines and to create a more respectable status vis-à-vis the public, the Sweden Democrats underwent a series of changes within their party program, policy suggestions and ideological model. Table 2 outlines a brief overview of the party’s official manifestos from 2002 to 2010. Some may argue that this ‘moderation’ does not necessarily mean that the Sweden Democrats actually or sincerely altered their political beliefs or principles. However, it is not overstating to assume that display and pretense to the public were in fact the purpose of this modification, rather than a genuine sanitization of the party’s ideology. Even though the party leaders were engaged in changing the party program and toning down its rhetoric, there occurred several incidents suggesting that the party still embraced radical and racist be they biological or cultural-attitudes, especially regarding the immigration issue.14

[Table 2.] Sweden Democrats’ Manifesto 2002-2010

Sweden Democrats’ Manifesto 2002-2010

Notwithstanding, we contend that the Sweden Democrats and their leadership gradually, but steadfastly, refined the party manifesto over the years, as shown in Table 2. First, they changed the party manifesto format from a prolix style reminiscent of declarations of social movements to that of a professional party platform of policy suggestions, which were written in a concise way and arranged in bullet points. Second, they refined the language used in the party manifesto, such that the party program was phrased in a professional and politically sophisticated manner. Third, the overall tone of the rhetoric increasingly became less provocative and aggressive. Lastly, and more importantly, leaders expanded the platform beyond the party’s main issue of anti-immigration to encompass social welfare issues in particular, such as elderly care and pensions. All of these changes indicated that the party was seemingly determined to weed out of the party program the extremism and radicalism of which it had been accused.

What stands out most were the modifications in key contents of the party program. In 2005, the party manifesto unwaveringly stressed that the Sweden Democrats were committed to democratic norms by explicitly supporting the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Such a move was in response to the criticism that the Sweden Democrats were a threat to democracy. However, the Sweden Democrats were industrious in turning the tables to reproach other elite parties and the media establishment for being undemocratic, especially since those elites and the media promoted neither deliberation nor freedom of speech when addressing the Sweden Democrats (Hellström and Nilsson 2010, 60; Widfeldt 2008, 272-273).

The Sweden Democrats also tried to forge its “own nationalist ideological niche” without “extremist connotations” by shifting its ideological model from the so-called New Right, as typified by Le Pen of France’s Front National, to that of traditional Swedish social democracy, stressing the concept of Folkhemmet [“the People’s Home”] (Widfeldt 2008, 272; Hellström and Nilsson 2010, 62). By constructing and adopting its own “Nationalist principle,” the Sweden Democrats took on a popular nostalgic concept and narrowed down the meaning of “the people” and “the people’s home” to “real Swedes.” Needless to say, the party intended to improve its image by winnowing down a “[mono]culturalist nationalism” and espousing a cherished and traditional metaphor (Hellström and Nilsson 2010, 63).

Sweden Democrats also de-radicalized their rhetoric on immigration policy. Specifically, they gradually toned down the slogans of the immigration policies over time from “restrictive” to “limited” and finally to “responsible.” Again, the skeptics could refute that the anti-immigrant and xenophobic sentiments on which the party built its

7For instance, both the Danish People’s Party and the Progress Party in Norway are typical examples of an anti-tax protest movement advocating for downsizing the public sector, in general, and government bureaucracy, in particular. 8His reform efforts, however, resulted in a party split in 2001. Some of the party’s most successful activists and sympathizers were expelled or defected to form a more radical party, Nationaldemokraterna. 9Åkesson joined the Sweden Democrats at the age of 15. He was politically schooled in the party’s youth organization and became the first party veteran when performing his duties as a trustworthy and strong leader as perceived by the party faithful. 10He called the party split in 2001 one of the most significant events in the party’s history, since “the fools who were still in our party could now leave.” 11When Åkesson appeared in brief TV interviews in the run-up to the 2006 elections and TV debates against leading politicians from mainstream parties in 2007, “his smart appearance, his lowkey but confident and reasoned style and his ‘clean’ background belied any accusations of extremism or quirkiness” (Widfeldt 2008, 271). 12The number of articles covering the Sweden Democrats multiplied from 99 in 1997 to 7,406 in 2009 (Hellström and Nilsson 2010, 69). 13For instance, Åkesson frequently held press conferences to voice his concerns that the Sweden Democrats were ‘underdogs’ and ‘democratic victims’ by citing his experience of being denied access to channels of political information, and he complained about having been denied freedom of expression. 14For example, even after the party program changed its stance over immigration in 1999, several party activists expressed their desire to evict non-European immigrants out of Sweden in harsher terms than phrased in the program (Widfeldt 2008, 272). In fact, the party was repeatedly involved in scandals related to racism and was even accused of anti-Semitism as late as December 2014 due to the remarks made by the party’s secretary and deputy speaker in parliament, saying that the Jews must abandon religious identity in order to be Swedish citizens (Expo 2010; Öhlén 2010; Crouch 2014).

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE: QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

In this paper, we argue that the Sweden Democrats successfully appealed to an electorate that was skeptical about open immigration but still remained unrepresented on the Swedish political scene. The party saw a clear niche in the country’s immigration policy, so leaders strove to reconstruct the party as a credible alternative to the mainstream parties. We contend that the Sweden Democrats managed to overcome the ‘barrier of non-respectability’ by moderating their political stance to achieve a belated electoral breakthrough. In order to verify our argument, we propose to test whether the internal supply-side factors, such as party leadership and party manifesto of the Sweden Democrats, significantly contributed to its belated electoral performance.

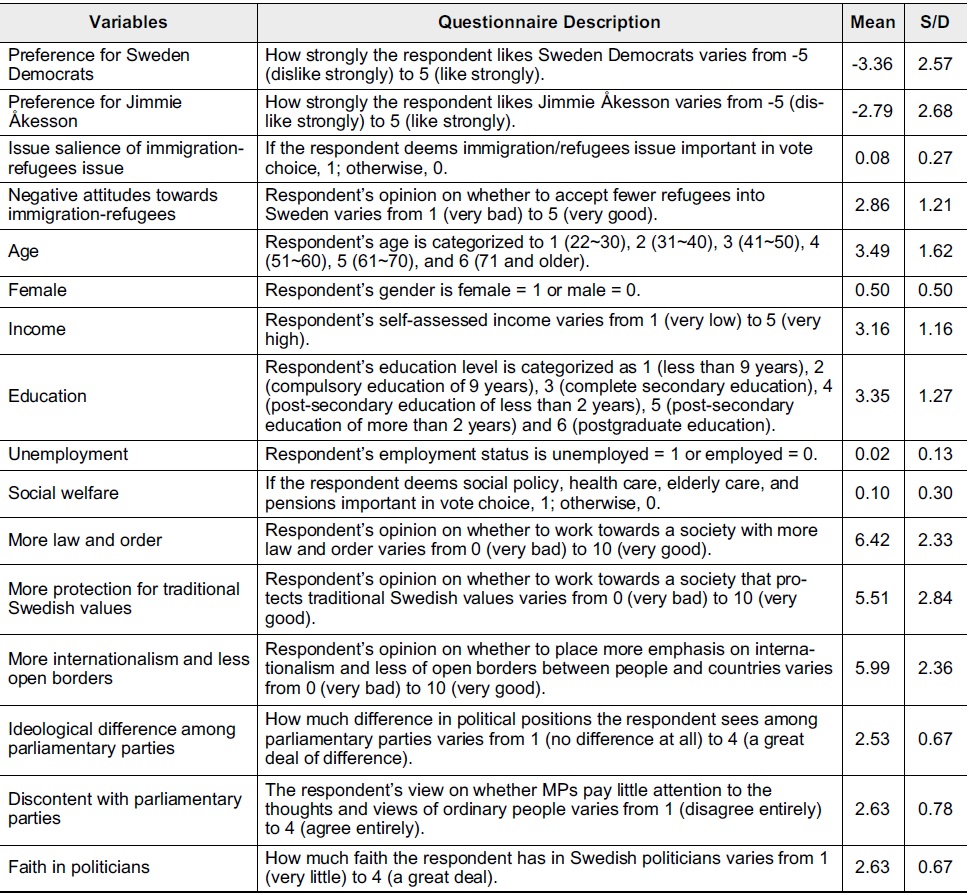

In this paper, we used the survey results of the 2010 Swedish National Election Study. The Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg and Statistics Sweden conducted these surveys. We obtained the data with the assistance of the Swedish National Data Service (SND). Much to our regret, we were unable to conduct chronological analysis because the survey questions regarding preference for both the Sweden Democrats and their leader were included in the 2010 National Election Study only but not in earlier studies. This deficiency in the data is understandable given that the Sweden Democrats had no meaningful presence on the national political scene prior to 2010.

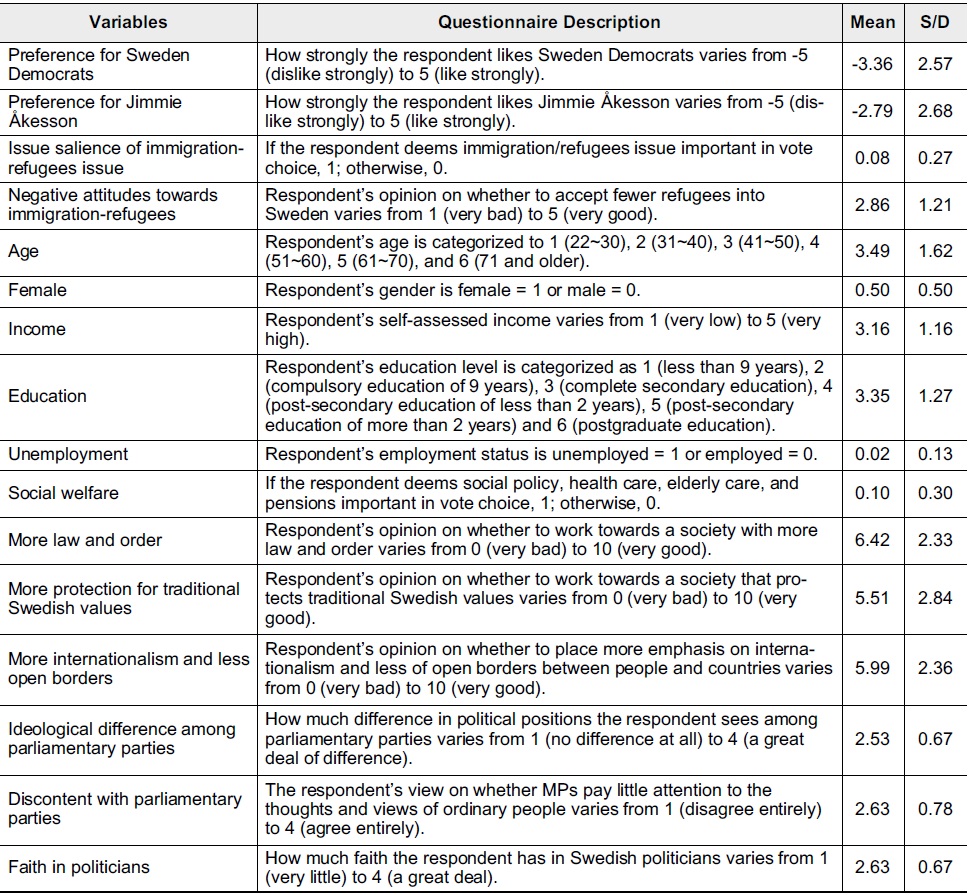

Our dependent variable is the voting preference for the Sweden Democrats, which ranges from -5 (dislike strongly) to 5 (like strongly). As seen in Table 3, our three independent variables are: preference for Jimmie Åkesson, issue salience of immigration-refugees, and negative attitude toward refugees in Sweden. First, since Åkesson arguably contributed in a crucial way to the party’s cleansed image and its upgraded profile, ‘preference for Jimmie Åkesson’ is viewed as an indicator of how successful the Sweden Democrats were with the normalization process. Second, assuming that the Sweden Democrats’ electoral breakthrough was based on its appeal to the niche in the immigration issue area, which had been dormant, we used two questionnaires from the survey to measure whether the immigration-refugees issue was mobilized when voting for the party, and whether the anti-immigration attitudes of voters conditioned such voting choices.

[Table 3.] List of Variables and Descriptive Statistics

List of Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Furthermore, we included interaction terms as listed in Table 3 to see if the voters who deemed the immigration-refugees issue politically important enough to restrict immigration also had affection for Jimmie Åkesson, thus systematically preferring the Sweden Democrats to other parties. In other words, the interaction terms will display, if and by how much the normalization process of the Sweden Democrats impacted the party preference of the electorate who were skeptical of open immigration, and which resulted in an albeit belated electoral breakthrough. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis A1: If the electorate has affection for Jimmie Åkesson, they tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis A2: If the electorate is skeptical about open immigration, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis A3: If the electorate finds the immigration-refugees issue politically important, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis D1: If the electorate has affection for Jimmie Åkesson and finds the immigration-refugees issue politically important, they are more likely to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis D2: If the electorate has affection for Jimmie Åkesson and is skeptical about open immigration, voters are more likely to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 3-1: If the electorate finds social welfare issues politically important, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 3-2: If the electorate finds law and order issues politically important, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 3-3: If the electorate finds more protection of traditional Swedish values politically important, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 3-4: If the electorate finds more internationalism and less open borders politically important, voters tend not to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 4-1: If the electorate sees no ideological difference among parliamentary parties, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 4-2: If the electorate is discontented with parliamentary parties, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 4-3: If the electorate lacks faith in politicians, voters tend to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

Hypothesis 4-4: If the electorate sees no ideological difference among parliamentary parties and is discontented with them, voters are more likely to cast their vote for the Sweden Democrats.

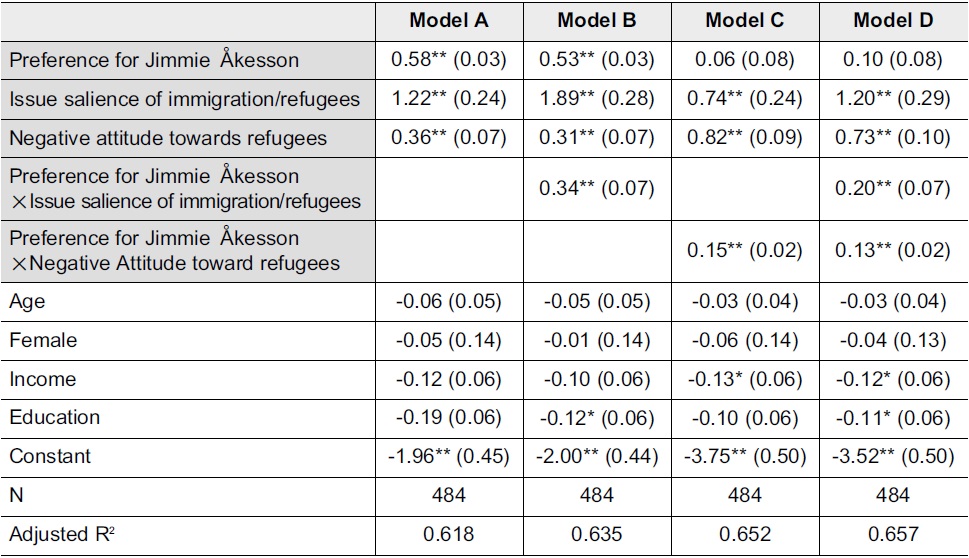

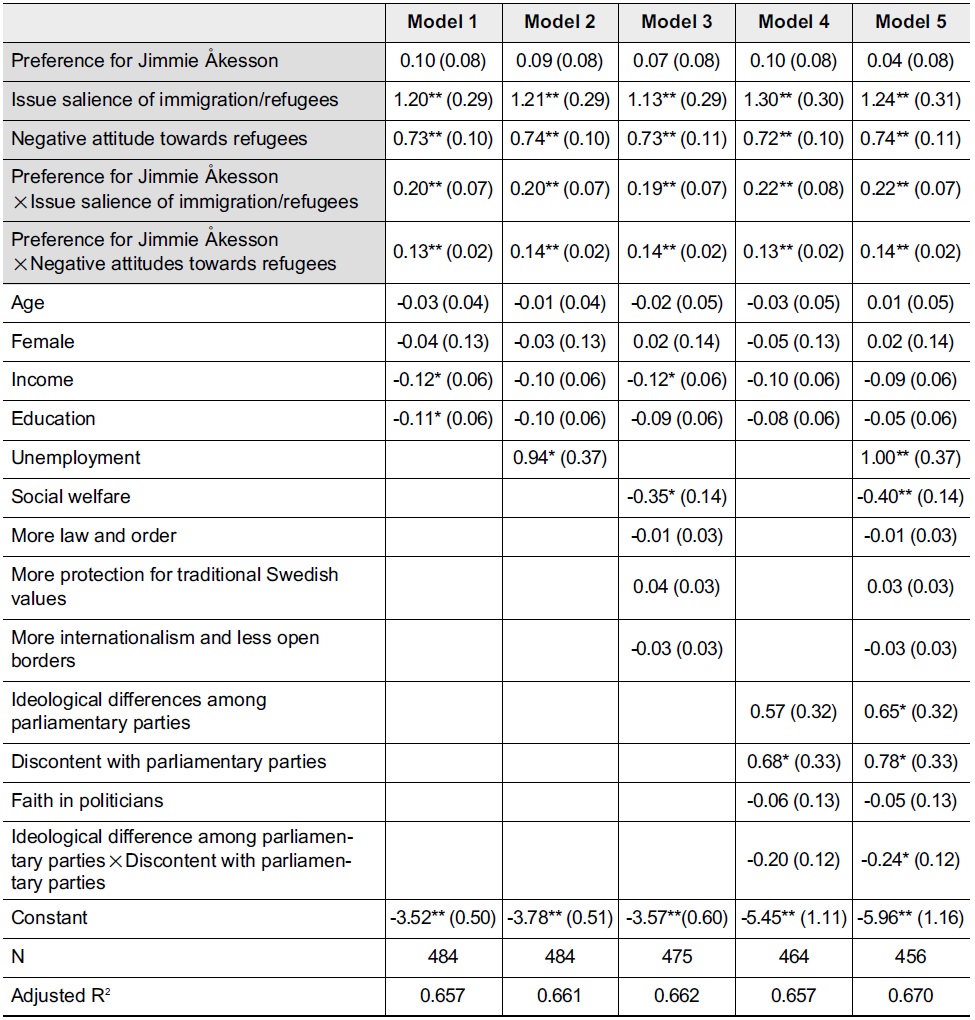

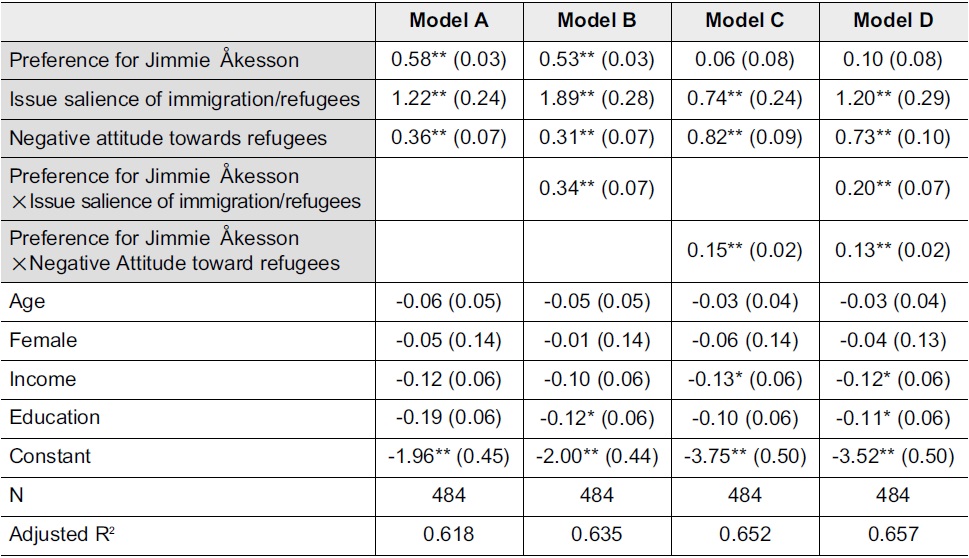

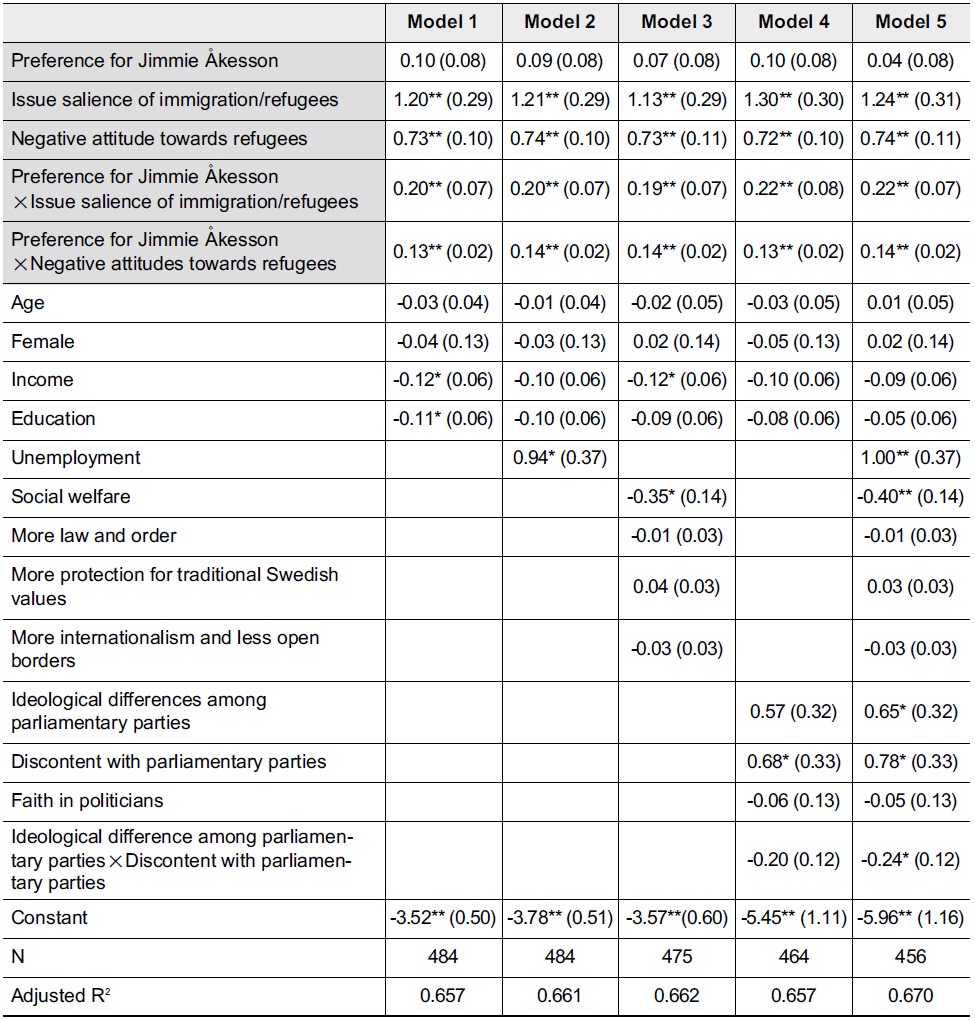

We estimated eight models in total by running ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression. Models A through D as listed in Table 4 show whether the three key independent variables and their interaction terms are statistically significant. Models 1 through 5 as listed in Table 5 extend the list of independent variables by adding a series of control variables, including anti-establishment sentiment along with the usual demographic traits. Table 3 also lists all descriptive statistics for variables that may condition the electorate’s vote choice.

Model Comparison I

[Table 5.] Model Comparison II

Model Comparison II

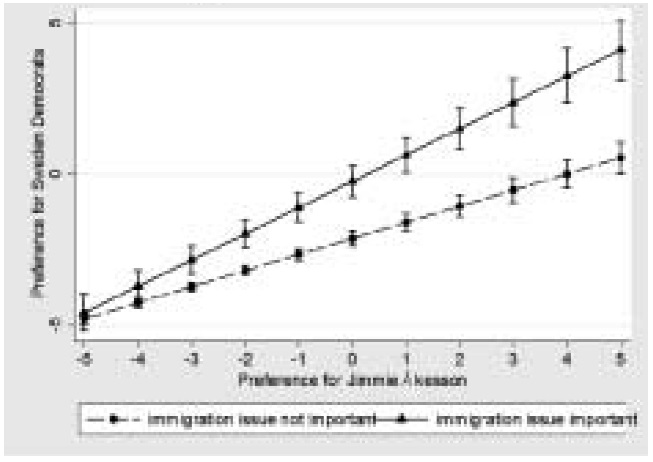

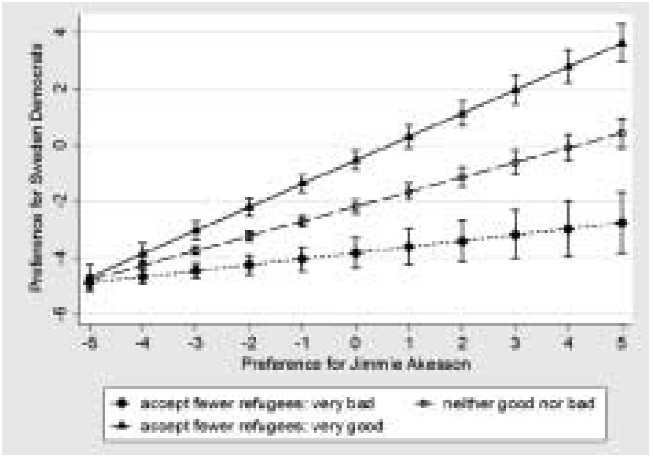

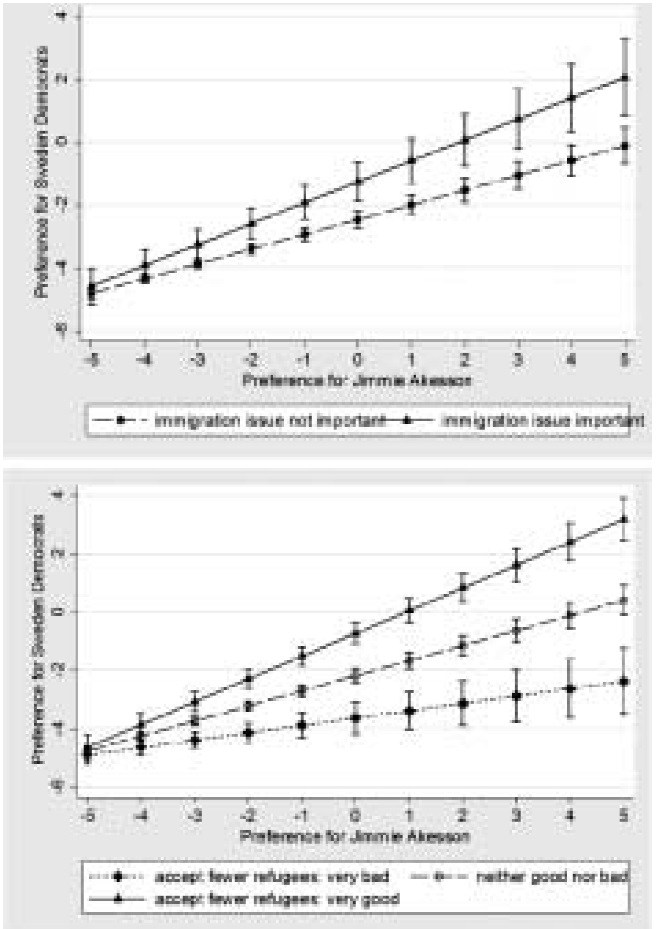

Table 4 shows the estimates of the OLS regression models to test the key independent variables against the preference for the Sweden Democrats. If a voter deems the immigration-refugees issue important, s/he is skeptical about open immigration, or s/he apparently has affection for Åkesson, all these factors respectively have a statistically significant impact on the electorate’s voting choice in favor of the Sweden Democrats [Model A]. We also find that the vote choice in favor of the Sweden Democrats is conditioned upon personal feelings for Åkesson [Model B and C]. The more a voter feels the immigration-refugees issue politically important, the more her/his preference for Åkesson inches closer to her/his vote casted for the Sweden Democrats [Model B]. Similarly, the more strongly a voter endorses the proposal to reduce the number of refugees, her/his personal likes of Åkesson boosts her/his decision to vote for the Sweden Democrats [Model C].

The impact of Åkesson’s charm on the preference for the party is conditional, both on whether a voter regards the immigration issue as important, and also if the voter strongly agrees with the proposal to reduce the number of immigrants. The interaction effects from Model B and C are more clearly visible in Figures 2 and 3. Among those who do regard the immigration-refugees issue as politically important, or whose anti-immigrant sentiment is exasperated by their advocacy to reduce the number of refugees, the slope of the predicted line becomes even steeper. What sets apart Model C from Model B, though, is that Åkesson’s charm dissipates with the inclusion of an interaction term between Åkesson’s charm and negative attitudes toward refugees as shown in Table 4.

Furthermore, the estimates from Model D in Figure 4 show that while the Åkesson factor does positively correlate with the preference level for the Sweden Democrats, the most statistically significant variable that explains the electoral support for the party is the voter’s opinion on whether to accept fewer refugees into Sweden. Accordingly, Åkesson’s charm no longer is statistically significant when both interaction terms are included in Model D. In connection with Model C, this indicates that Åkesson’s charm contributes to the electorate’s voting choice for the Sweden Democrats

The findings from Model D confirm that a popular leader can draw support for the party

We further estimated more models with control variables as shown in Table 5 to test the robustness of our core independent variables. To make our analysis more concise, Model 5 shows that all key variables, with the exception of Åkesson’s charm, were strongly correlated with the dependent variable of vote preference for the Sweden Democrats even after controlling for other variables possibly attributable to their electoral performance. Among those control variables shown in Table 5, unemployment was positively correlated with support for Sweden Democrats [Model2]. This is in line with previous research that explains the rise of anti-immigration parties in Western Europe by relying on the ‘modernization losers’ or ‘relative deprivation’ perspectives (Betz 1994; Lubbers et al. 2002). When contrasting Model 2 against Model 1, it is also interesting to note that the demographic variables such as education and income level lose their meaningful influence on voting behavior after the status of employment is added as a control.

Moreover, it is equally interesting to note from Model 3 that policy issues other than the immigration-refugees issue, which features strongly in the platform of the Sweden Democrats, have virtually no or even negative correlation with party support. Model 3 shows that the voters who deem welfare issues important when choosing their party are not entirely comfortable with the Sweden Democrats. Although Sweden Democrats vigorously promote welfare policy issues, especially elderly care, this finding rejects Hypothesis 3-1 and confirms that the party base is primarily built on the anti-immigration issue and not much else.

The impact of other policy proposals, such as more law and order, more internationalism and stronger support for traditional Swedish values, on the choice of voters for the Sweden Democrats is not statistically significant. For voters who put emphasis on law and order, they failed to differentiate the Sweden Democrats’ narrative from the anti-establishment stance and rhetoric of other radical parties. This finding rejects Hypothesis 3-2 and confirms that the party’s emphasis on more law and order inadvertently drove the voters away from the Sweden Democrats. We conjecture that this is probably because the Sweden Democrats mobilized those with any anti-establishment sentiment. As expected, voters also shied away from the Sweden Democrats who vigorously advocated for

It is reassuring to find Model 4 in accordance with our argument: the Sweden Democrats proved the party’s worth on the basis of an anti-establishment sentiment. Table 3 earlier showed the range of 1 (no difference at all) to 4 (a great deal of difference) to the question asking how much difference voters sees among parliamentary parties in political positions, which yielded a mean of 2.53. Table 3 also showed the range of 1 (disagree entirely) to 4 (agree entirely) to the question that inquires how strongly voters disagree or agree with whether the incumbent MPs pay little attention to the thoughts and views of ordinary people, and this yielded a mean of 2.63. Despite the lack of statistical significance, voter perception of ideological differences among parliamentary parties contributed to the tendency to vote for the Sweden Democrats. Moreover, to the voters who were unhappy with their MPs and disapproved of their performance, the Sweden Democrats appeared to be a viable alternative as a legitimate political voice to represent their grievances. The party appeal among discontented voters was statistically significant.

Such anti-establishment sentiment substantiates the conventional wisdom that if voters put their faith in politicians, they tend to stay away from the Sweden Democrats, although such a negative correlation is not statistically significant. It remains unclear, however, how anti-establishment sentiments have been translated into the belated electoral success of the Sweden Democrats. Accordingly, we include an interaction term in Model 4 to test whether and how the voting preferences for the Sweden Democrats are conditional upon anti-establishment sentiment. Despite the lack of statistical significance, we find it perplexing that the interaction term between the voters’ discontent for their MPs and their perception of no ideological differences among parliamentary parties only dampens their likelihood to vote for the Sweden Democrats.

In Model 5, we test the robustness of anti-establishment factors, especially the interaction term between the voters’ discontent with their MPs and their perception of ideological differences among parliamentary parties by putting all the variables together. Appendix 2 also illustrates the effect of this interaction term so that we can further examine what the negative sign of its coefficient in Model 5 indicates. As the voters are increasingly able to differentiate parliamentary parties based on their political positions, they are drawn closer to the Sweden Democrats with whom they perceive to associate a viable policy alternative. Voters also tend to vote for the Sweden Democrats if they are dissatisfied with their incumbent MPs. Combined, the interaction term is also statistically significant in conditioning the voters’ preference for the Sweden Democrats. As opposed to the group of voters who perceives great differences between the parliamentary parties, the voters who see no difference at all become more likely to prefer the Sweden Democrats as they increasingly agree with the statement that “parliamentary parties are not interested in ordinary people.”

However, this interaction term has a negative sign, indicating that the impact of anti-establishment sentiment on the voter’s preference for the Sweden Democrats dampens. This raises a further research question as to what conditions the voters are restrained despite their frustration over open immigration and their discontent with their incumbent MPs. We conjecture that voter preference for the Sweden Democrats is conditional upon the level of politicization, which we intend to pursue in subsequent work.

While Europe has witnessed the rise of the far-right since the 1970s, Sweden for quite some time had escaped such an event despite ripening public opinion in opposition to open immigration policies. Aside from the short-lived New Democracy, no anti-immigration parties also labeled radical right parties rose to gain substantive electoral support in Sweden. However, this exceptionality and abnormality began to wane as the Sweden Democrats, the Swedish antiimmigration party borne from a neo-Nazi background, successfully sidestepped electoral marginalization in the 2010 and 2014 national elections, thereby eventually growing to be the third largest party in the national parliament. This paper has attempted to account for the delayed electoral breakthrough of the Sweden Democrats by focusing attention on party-centric or internal supply-side factors.

It is our main argument that earlier studies somewhat overlooked or downplayed the internal supply-side factors, or factors central to the party itself, when accounting for the success or failure of the Sweden Democrats in particular, or anti-immigration parties in general. This paper distinguishes itself from previous works that dwelled on Sweden as an unsuccessful case because we strove to show that the origin of the Sweden Democrats, and its stigma associated with the past, propelled party leadership to overcome internal conflicts and breakaway from that damaging image. The party was able to accomplish its objectives only when party leadership could prove to be decisive in moving forward with its transformation to a significant minority of voters who became gradually disillusioned with open immigration in Sweden.

This paper confirmed that the Sweden Democrats marked a watershed moment in 2005 with the change of leadership who were able to successfully mobilize dormant voters in the area of the anti-immigration issue. This change in party leadership itself, however, was not sufficient to create a niche in the national political scene. The personal charm of Jimmie Åkesson had to enlist those whose political voices remained unrepresented by building a new party image cleansed from its neo-Nazi heritage and reestablishing itself as a party conforming to democracy. This paper also uncovered that those who chose to vote for the Sweden Democrats because of their dissatisfaction with the

The context of such mitigation is left for further research. We speculate, though, that this initial finding may further bolster the claim that electoral support for the Sweden Democrats was conditioned upon the perceived viability of a more restrictive immigration policy, which eventually drove some discontented voters to finally endorse the Sweden Democrats. Others who still identified ideological differences between the established parties, and thus were provided with a political alternative other than the Sweden Democrats, refused to cast a ballot for the Sweden Democrats despite their dissatisfaction with the status quo. It should suffice to conclude in this paper that the voters’ discontent with their incumbent MPs reinforced their preference for the Sweden Democrats