Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lived only by sucking on living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.

Karl Marx

Well, you might be surprised to know that the specters that frequent such places will show up in broad daylight in Seoul, which as we all know is a civilized city. And the more Seoul develops and flourishes, the more specters we see there.

Yi Hyo-sŏk (translated by Youngji Kang)

In Yi Hyo-sŏk’s short story written in 1928, “City and Specter” (Tosi wa yurŏng), the main character describes an encounter with a specter that he at first mistakes for a goblin (tokkaebi). Attempting to face his fear, the protagonist returns to the site of his ghost sighting, and it is revealed that what he thought was a specter was in fact a mother and a child, a “pair of beggars.”1 Upon meeting these colonial “ghosts,” the protagonist instead discovers true horror in the mother’s condition: “from the ankle down, nothing was there, her calf was twig-thin, and the stump was still raw and deathly blue.”2 Although the narrator rushes away after thrusting money at the pair, this encounter with wandering souls reveals the putrid under-belly of Chosŏn modernization. The narrator who had previously enjoyed walking down the “teeming streets” on one of Seoul’s beautiful summer nights is horrified by the growing Chosŏn poor, who he describes as “alive but. . . as good as dead.”3

Yi’s short story addresses not only the material realities of uneven modern-ization—the mobilization of resources under colonial capitalism, labor shortages and rural pockets of extreme poverty—but also the ways in which these issues are packaged within the socio-symbolic. Exhibiting the persistence of folk beliefs within the narrative of modernity, the cultural representations that filter this complex constellation of structural developments also captures the anxieties of the period as people are displaced and swept along with colonial capital flows. Although Yi’s short story uses the word “specter” and “goblin” to describe this anxiety, this article will focus on a more common specter in colonial mass culture: the starving ghost (agwi, 餓鬼).

Agwi, alternatively described as “starving ghosts” or “ghostly souls,” appear in the Buddhist tradition as spirits or demons who have been committed to an immortal existence of insatiable hunger. In the modern context, starting in the 1920s, agwi became sociosymbolic images of poverty appearing frequently in 1920s and early 1930s cartoons, news columns and literature about the proletarian masses. By proletarian masses, I refer to representations of mostly laborers and tenant farmers, those economically and socially marginalized in colonial Korean society.

The argument introduced in this article is twofold. For one, the incor-poration of the agwi in 1920s and 1930s mass culture suggests the different ways we can understand the modern experience. The haunting of the agwi inspires questions about the repackaging of the symbolic order within the colonial modern context and challenges the artificial boundaries between antiquity and the modern, under the modern critique of the “superstitious” and the “folk.” I argue that the agwi is an example of modern sensibility in its very reproduction, reuse and repackaging vis-a-vis a constellation of sources that demonstrate the increasing convergence of semiotic meanings across varied textual and visual representations.4 This work is inspired by scholars who may work on different localities but that have similarly discussed fantastical narratives as representative of the tensions between “old and new forms of knowledge”5 at certain transitional moments in modernity.6

Secondly, the “horror” of the agwi arises in its very material grounding in the colonial experience and in its many suggestive interpretations of labor, capital and poverty. The agwi is both particular to this historical context but representative in many ways of Karl Marx’s own gothic critique of capital that describes capital as sucking “living labor” and swelling in size. The semiotic power of the agwi arises from its many iterations and simultaneous fluidity: alternatively the culprit, wreaking havoc on Koreans, but sometimes a specter embodying the Korean people, an incarnation of impoverished people in the rural provinces and shantytowns.

1Thank you to my anonymous reviewer who directed me to this short story. Yi Hyo-sŏk, “The City and the Specter,” trans. Young-ji Kang (University of Hawaii Press, 2013), 100. 2Yi, “The City and the Specter,” 101. 3Ibid., 103. 4Though Lisa Cartwright discusses the term “media convergence” in the context of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, Bliss Cua Lim supplements this idea with the example of the aswang (a vampire-like mythical creature in Filipino folklore) and its multiple cultural reincarnations from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. As Lim suggests, the aswang effect is its “media convergent” eventfulness, continually re-manifesting at different temporal moments. 5Gerald Figal, Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999) 17. 6See Bliss Cua Lim, Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009). See also Susan J. Napier, The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature: The Subversion of Modernity, (London and New York: Routledge, 1996).

An editorial called “Let’s Do Away with Superstition,” published in August 6, 1925 discusses the problem of superstition in Korea in the race of civilizations:

The author, in his description of what makes a country uncivilized, calls out against specifically “suicides and agwi” that afflict the Chosŏn people, telling them that they must adhere to “scientific thought” (minjungjŏk chŏngsin) and eliminate such backward superstitions. Editorials like this that address occult forms and the disease of “uncivilized thought” persist into the 1930s and continuously call for the fostering of the “foundations of scientific knowledge.” Although ten years later, the author of a similar 1934 editorial also bemoans the backwardness of the Chosŏn people, he differently identifies the main problem as being Korean women, who he blames as the root of persisting and increasing belief in superstition.8

Such editorials echo the familiar dichotomy between civilization or modernization against the past, positing rational modern discourse against folk beliefs, ghosts and the supernatural, attempting to expel these “out-of-sync” elements from the discourse of the modern. However, while these editorials decry the “cracks” in Korea’s modernization during the 1920s and 1930s, a wider scope of the newspaper platform presents a different temporal representation of the nation.

Perhaps the most visually obvious indicator of this temporal representation are the reader-submitted cartoons (tokcha manhwa) that frequent the pages of print culture during these two important decades. Reader-submitted cartoons became especially frequent from 1923 through efforts by daily newspapers such as the Chosŏn ilbo and Tonga ilbo to incorporate print cartoons. The Tonga ilbo, in particular, incorporated a reader-submitted cartoon by Kim Tong-sŏng from its first publication in 1920, and the Chosŏn ilbo followed suit with “pen drawing” (ch’ŏlp’il sajin) in 1923. Although there were “professional” cartoonists such as Kim Tong-sŏng, who continued to publish his signature four-paneled cartoons in Tonga ilbo, and No Su-hyŏn, who wrote the serial cartoon “Idiot” (Mŏngt’ŏngguri), for the majority, the cartoons were reader-submitted and, often times, the roughly drawn sketches reflected their amateur nature. There were efforts by these newspapers to integrate cartoons through contests for cartoon submission, and most cartoons were in fact submitted anonymously.9

To give examples of the nature of these contests, on May 14, 1923, Tonga ilbo released an announcement for theses, short stories, poetry and cartoons on “contemporary issues.” This was followed with another announcement on December 1, 1923 for “Asian cartoons” (Tonga manhwa) on national politics, economic issues, and social problems. The publication of cartoons continued until 1928, when the newspaper was subjected to multiple suspensions. The interesting submission process and the anonymity of the cartoonists show how mid-1920s mass culture involved a kind of participatory readership and illustrate local contact, the “collective” imagination within print culture. Individuals would submit from different provinces, and although many of the cartoons represented local, specific issues, there was a shared association of symbols regarding oppression. The production and recognition of these images were central to the circulation and effectiveness of these ideological representations.

Many of these reader-submitted cartoons focus on common problems of the lower classes. This cartoon (Figure 1), which was published in 1925, addresses the kind of mass discourse that surrounded the rising population of unemployed Koreans. In the cartoon, a giant-sized monstrous agwi looms over the Korean peninsula as Korean laborers (Chosŏn nodongja) flee to Japan. Mirroring similar reportage at the time that describes the itinerant tenant farmers as being “chased out by agwi,” the scale of the starving ghost reflects the affect of the times: an overwhelming sensibility of terror and despair. Although a simplistic rendering, the illustration successfully directs attention to unrest caused by uneven 1920s colonial agricultural policy, changing land ownership and tenant tariffs.

As a result of these reforms, it was during this time that many farmers became wage farmers, and an even larger amount of people who could not be assimilated into the labor industry joined the unemployed masses. Ken Kawashima describes these populations of Koreans who migrated during the 1920s and 1930s as “surplus populations,” who often wandered and remained “in limbo” and “in conditions of extreme contingency and precariousness.”10 Figure 1 in particular suggests how this “in limbo” status was articulated in Korean print visual culture.

Although Kawashima has used the term “in limbo” to describe the wandering state of laborers uprooted by uneven capitalism, I am doubly interested in the term “in limbo” because of its temporal implications. As much as “in limbo” describes the wandering and necessary emigration of Korean laborers under Japanese imperialism, it also adds a spectral ontological quality that captures certain temporal and spiritual conceptions of labor during the 1920s. Specifically, “in limbo” brings to mind the association of souls “in limbo,” caught between two stages of spiritual existence and on the borders of hell.

Although the illustrations and reportage on agwi during the 1920s and 1930s carry much of the connotations of their traditional counterparts appearing in the Korean Buddhist visual tradition,11 they are also different in their modern form. The popularization of the agwi as a type of psychological possession, ghost or spiritual threat for example would not have been encouraged by Buddhist spiritual leaders. These descriptions that materialize the agwi within colonial daily life would have been considered a type of folk superstition that “enlightened” Buddhists believed was an obstacle to modernization.12 On this matter, Korean Buddhist leaders, Christians, and the government-general were aligned in concentrating their efforts against “irrational” spiritual activities that resembled shamanistic rituals with spirits and ghosts. This represents one of the ways in which the fantastic is often argued to be an obstacle to modernity, but is in reality was produced and transformed by modernity itself. As Gerald Figal suggests, modernity itself is “phantasmagoric; it ceaselessly generates that which is a la mode by consciously imagining difference from things past.”13

The persistence of the recurring image of the starving ghost in discussions of poverty, labor and the lower classes suggests the grotesque implications of the agwi within the colonial regime. The starving ghost appears against backdrops of despair: spreading poverty in the rural areas, natural disasters that plague the tenant farmers and mass emigration of Korean laborers. Mark Driscoll, in his application of Foucault’s notion of biopolitics, has described Korean labor under Japanese imperialism as a shift from “living labor” to “commodifiable dead labor,”14 which was accompanied by a culture of “grotesquing” rendered by the biopolitical power of the imperial regime. Although Driscoll locates this “grotesquing” mainly within imperial discourse, the cartoons about Korean laborers during this period shows how we can ask the same question of 1920s Korean mass culture, as it differently and similarly interprets worsening labor conditions and the subjective shift under global capitalism. The agwi as grotesque is a fluid figure that is simultaneously the perpetrator and the victim, mirroring the very contestations, contradictions and tensions of colonial Korea.

An article, in 1924, describes 200 people in a town in Pyŏngwŏn-gun in a northern province who “starved and starved until they finally sold their huts and left their village for the south.” The article describes how the 200 residents of the village felt that, if they stayed, their fate was “to become agwi themselves” so they moved to Kangwŏn Province, Chŏrwŏn-gun, because they heard of employment there on a farm. The article brings up the uncertainty and desperation that surrounded the move as all the people, both young and old, were uprooted without any employment assurance and knowledge of the unfavorable land tax situation awaiting them.15

Within the newspaper platform, cartoons and articles referencing the starving ghost coexist side by side, presenting an interesting temporal continuum. As Bliss Cua Lim suggests in an application of Benedict Anderson’s notion of “imagined community,” the inclusion of ghosts and the supernatural in newspapers help bind the “nation’s illusory temporal homogeneity” and suggest an “acknowledgement of enchanted temporalities hidden in the penumbra of national time.”16 These supernatural elements that are often associated with peasant, folk “premodern” beliefs emerge within the frame of the modern time of the newspaper and are presented as the complete imagination of the nation.

Despite these inclusions however, these supernatural elements exclusively emerge in the context of the proletarian masses. The uneven concentration of supernatural renderings exclusively about the rural areas and not the city suggest hidden discrepancy and difference under modernization. We can extend this idea to the imperial center and colonial peripheries, as the agwi, existing on the boundary of the living and dead, also illustrates the subjugation of labor under imperial-colonial capitalist production.

Figure 2 captures the “horror” of the approaching agwi as it devours the Korean peninsula: the ghost illustrated in a similar way with the previous cartoon example, with horned head, and starved body. The one difference between the two images is that the illustrator has drawn the ghost with fins for feet, which differs from other depictions of the agwi in print culture and suggests that the agwi swam across to the peninsula from another source. The cartoon is captioned with the words: “Famine! Famine!” and, as can be seen by the illustration, the agwi is semiotically saturated with sensations of horror. As Driscoll and Kawashima have emphasized, an important facet of Japanese colonialism was the physical depletion of the bodies of the colonized. Especially in the 1920s when the export of Korean rice to Japan reached 40 percent of the country’s total rice production,17 the biopolitics of the Japanese colonial empire—enriching the bodies considered most valuable and letting those considered “disposable” die—is emphasized.

The concern with famine in rural villages is echoed in a majority of reports during the 1920s that describe villages on the brink of death, in danger of “becoming agwi” or becoming an “agwido” (hell of the starving). In a report in November of 1924 called, “Shantytowns: six different worlds,” the writer writes a kind of exposé of shantytown villages and their horrible conditions. Of one such village, the writer reports that, far worse than the poverty witnessed in Sindang-ri, he has discovered a new village that surpasses the others, an “agwi cave” he calls it.18 Unable to “fight back tears,” the reporter says it is hard to believe that the villagers are indeed “people.” There is an accompanying picture of the shantytowns that the author writes the exposé on (Figure 3).

The very corporeal nature of these reports are permeated with visual imagery of life and death: “With our blood, sweat, money and rice, let’s try our best for our brothers and sisters in the surrounding areas who are entering the agwido…”19 In the excerpt from the column, the starving people who are entering a state of the living dead are contrasted with the vitality of the living. The very biopolitics of the state are echoed in the descriptions of villagers: their corporeal virility is intertwined with capital, while the surrounding wilting areas are depleted with life.

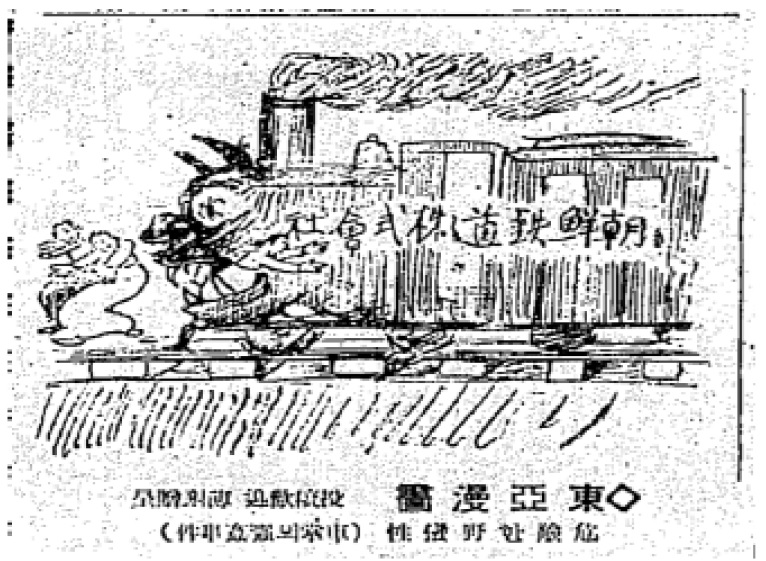

Although in the previous example the starving ghost materializes on account of poverty or misfortune, alternatively modernization is also represented as a starving ghost as well. A direct vilification of modernization, this cartoon (Figure 4) demonizes the railroad or, more broadly, capitalism and imperialism as re-presented by the railroad.

The train has the words “Railroad Corporation” (Chosŏn ch’ŏlto chusik hoesa) and criticizes the increasing expansion of railroads during the 1920s. Hubs of transportation such as Seoul Train Station became symbols of the sinews of imperial power and influence, as Japan depended heavily on trains to transfer goods to implement its military presence.

Agwi are also used interchangeably with natural disasters associated with the plight of the masses that are, albeit secondarily, also involved with production. Figure 5 illustrates how the horrible conditions in the country villages were exacerbated by natural disasters, lack of medicine, poverty and sickness; the starving ghost that gobbles the masses is labeled with the words “sickness” (pyŏngma). Natural disasters such as flood and fires permeated reports at the time as well, and agwi can be located at the heart of these narratives that describe rural villages devastated by disaster. In many reports of natural disasters, it is not the disasters themselves that cause the death of the villagers but rather the depletion of resources after the disasters that cause death. The image of the agwi feeding on the Korean people perceives of natural disasters as being a type of supernatural damnation.

Culminating in the late 1920s, some of the reportage on devastated rural areas called for mobilization of troops to help “agwi villages” (agwido). The inundation of reportage foregrounds the project relief efforts led by the colonial government under Saitō Makato that were implemented from 1931 to 1935 to alleviate the poverty in the countryside and prevent the movement of people from Korea to Japan, which the colonial government saw as an extra burden on the great depression that had already infected the empire. Though the relief efforts concentrated on the infrastructure of the peninsula—railroads, dams, roads and rural facilities—the effort also tried to alleviate the unemployment problem by providing jobs through these infrastructure developments.

The agwi continues to be an important cultural marker of proletarian suffering during these 1930s relief efforts and the most famous example is Korean writer Chang Hyŏk-chu’s short story: “The Hell of the Starving”20 (Agwido). Although written in Japanese, it was widely publicized and discussed in Korean newspapers in the early 1930s. The proletarian literary short story incorporates the idea of the starving ghost into its description of a Korean labor camp working on a dam reconstruction in North Kyŏngsang Province. This literary example shows the continuing strong association between the starving ghost and the lower classes. However, as Samuel Perry has pointed out, Chang, in his detailing of the village and Korean villagers, often uses language that has been interpreted as a description of Korean exotic difference, rather than a universal tale of proletarian suffering.21 As a Korean writer in Japan, Chang highlights the ambiguity in colonial labor as it is interpreted by proletarian writers educated in the imperial metropole

7Kim Kyŏng-ji, “Let’s Do Away with Superstition” (Misin ŭl t’ap’ahada), Tonga ilbo, August 8, 1925. 8“Let’s Do Away with Superstition” (Misin ŭl t’ap’ahada), Tonga ilbo, April 20, 1934. 9Seung-hee Lee, “Socialist Politics and the Cultural Effects of the Newspaper Cartoons in the 1920s,” Sanghŏ Hakhoe: The Journal of Korean Modern Literature (2008): 77–112. 10Ken Kawashima, The Proletarian Gamble: Korean Workers in Interwar Japan, (Durham: Duke University Press) 12. 11The agwi as Buddhist iconography is most noted in Korean Nectar-Ritual Paintings (kamnodo) produced during the Chosŏn dynasty from the sixteenth century to the twentieth century. This semi-narrative painting genre named after “nectar” (kamno), the sweet beverage that symbolizes “Buddha’s grace,” usually depicts the guiding of wandering souls from their suffering and pain to salvation.3 This genre is related to the Ullambana Sutra, which recounts the lesson that Buddha gives the monk Maudgalyayana. Maudgalyana hears that his mother has become a starving ghost because of her greed in her past life and travels to the spirit world to provide her with food. Maudgalyana discovers that his mother cannot be fed, and that she can only be saved with prayer. In this way, the Ullambana Sutra touches upon both notions of Confucian filial piety and Buddhist eternal salvation through rebirth. For more on kamnodo, see Henrik Sorensen, The Iconography of Korean Buddhist Paintings, (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989). 12See Pori Park, “Korean Buddhist Reforms and Problems in the Adoption of Modernity during the Colonial Period,” Korea Journal (Spring 2005): 89. 13Figal, Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan, 14. 14Mark Driscoll, Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living Dead, and Undead in Japan’s Imperialism 1895–1945, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010): 18. 15“Be Well, Hometown of Sanch’ŏn” (Kohyang Sanch’ŏn chal itkŏra!) Tonga ilbo, November 17, 1924. 16Lim, Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique, 101 17Driscoll, Absolute Erotic, Absolute Groteseque, 112. 18“Travelogue of Poor Villages: Six Different Worlds” (Pinminch’on t’ambanggi yuk pyŏl tarŭn segye), Tonga ilbo, November 12, 1924. 19“Let’s Quickly Help our Starving Brothers” (Kigŭn hyŏngjae rŭl ppalli kuhaja), Tonga ilbo, February 13, 1925. 20Chang Hyŏk-chu, “The Hell of the Starving” (Agwido), in A Collection of Chang Hyŏk-chu’s Short Stories, trans. Sirakawa Yutawa (T’aehaksa, 2002), 5–58. 21Samuel Perry, “Korean as Proletarian: Ethnicity and Identity in Chang Hyŏk-chu’s ‘Hell of the Starving,’” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique vol. 1 no. 2 (Fall 2006): 279–309.

As can be seen by its many representations, within the same newspaper space the figure of the agwi is not singular, but in its varied transmutations was used to stand in for structural agents of oppression that caused the extreme poverty of the lower classes. Appearing in articles that pointed out the material issues that afflict the lower classes, the agwi, at first sight, may seem like a disjunctive supernatural image that stands in for external oppression. Yet, upon a closer look at the constellation of media, the figure of the agwi communicates not only “outside” perpetrators of oppression but also the transformation of Koreans under agwi possession. The circumstances of agwi possession range from negative and sensational rumors of cannibalism to perhaps less common powerful images of class anger. The range of agwi representations suggests further that negotiating circumstances of colonialism, capitalism and modernity created ambiguous and tense material and emotional landscapes.

Although not directly alluding to Marxism, many of these images conjure up Marx’s words that likened capital to the intimate relationship between a vampire and his victim: “Capital is dead labor which, vampire-like, lived only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.”22 Like this gothic metaphor, the agwi that feeds on and possesses Koreans is horrific because of its intimate connotations of the dead living off the living. Traditionally, the image of the starving ghost can be traced back to sixteenth century Korean Buddhist images, such as nectar ritual paintings (kamnodo), that narrate Buddha’s teachings. However, the belief that agwi could participate in daily cultural life and possess people had been frowned upon by both intellectuals and Buddhist leaders as a type of superstition and a hindrance to Korea’s modernization process. The use of agwi in daily life reference as a type of supernatural folk belief is instead considered a mixture of shamanistic, Confucian and Buddhist principles.23

Because of the strong influence from shaman principles, the critique of capital intersects with cases of poverty because commonly shamans held a central position in protecting villages against natural disasters.24 As pockets of rural villages were excluded or “left to die” under colonial restructuring, the translation of such uneven modernization is communicated as the chaos and unbalance of natural spiritual order, resulting in a flooding of harmful spirits into the human world. The haunting of the agwi projects a permeable border between the profane and sacred, a border that the starving ghosts can pass through to wreak havoc on the living. These ghosts are most likely ghosts or spirits that had some sort of grievances in life, or died under bad circumstances. Because of the poor material conditions of the 1920s and 1930s in the rural areas, this suggests a correlation between the number of deaths due to starvation and the frequency of agwi “sightings.”

The representation of the agwido, entire villages that become the habitations of the living dead, extends these ambiguous temporal and spiritual boundaries. The agwido is traditionally located in a separate temporal spirit world but, as discussed in the previous section, the convergence of media in the figure of the agwi projects rural villages as “death worlds,” or what postcolonial theorist Achilles Mbembe calls “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.”25 Representations of the agwido disproportionately suggest that only certain spaces and groups of people—rural areas, tenant farmers, laborers—commonly left behind in the modernization progress are subjected to this spiritual damnation. Although presented within the secular narrative of modernity in the pages of the newspaper, the news reports are uncanny, feeding off overlapping fears of spiritual condemnation and material hardships.

Figure 6 is a visual portrayal of agwi possession, and illustrates the kind of sensations employed in descriptions of agwi possession. The image of the agwi wrapped around the man and devouring his head is violent, ghastly and intimate. The words written on the agwi and the man direct the viewer to the symbolic themes at hand. The agwi has the words “famine” (kigŭn) on its body, anguish/worry about the new era on its cheek (komin, sidae), and the word “threat” (hyŏppak) on its arm. The agwi is devouring a man who is a representation of Korean youth (ch’ŏngnyŏn) and strains for a weapon that is out of reach.

The words that should symbolically ground the agwi instead present a very general and emotional interpretation of the concerns involved. Overall, the image projects a helpless view of the future generation, immobilized in the face of daunting anxiety and uncertainty.

Unlike this cartoon, news report accounts of agwi possession rely on a mixture of reportage and fantasy; rumors or secondhand reports provide most of the information for events occurring in remote places. Projected as a supernatural threat, fantastical slippages occur in reports like this one from 1929 that reports about the northern provinces in China, near the Hamgyŏng region. It details an account of starvation and cannibalism in a village:

The article proposes a mobilization of troops to ban cannibalism in the northern areas, and addresses the issue of agwido created by lack of food. The article written by Tonga ilbo staff and positioned from the colonial urban center interprets the villagers’ cannibalism through this horrific image of supernatural possession by agwi. Sensational in nature, it views this isolated northern province as a primitive barbaric space that has succumbed to animalistic compulsions.

Similar reports to this were also reported from the early 1920s. In a report from August 1921, the writer discusses a fire suicide of 300 people that happened in Russia (Noguk). The reporter describes how in a “village in Russia” the villagers were so starved that in the end they set themselves on fire in a group suicide to avoid living on in an “agwido.” The wording of this account ascribes a spiritual quality to rural starvation: “living dead” status, becoming a starving soul and tormenting the human world, as being a state far worse than death itself. The geographic vagueness of the report also confuses the difference between fact and rumors.

Alternatively, newspapers also included exposés on people living in rural pockets of poverty; one such interesting account includes a transcript of an interview with the leader of twelve prostitutes in Chŏngjin village in Hamgyŏng Province. Protesting their working conditions—specifically rape, physical abuse and fraud—the women, with starved, haggard faces and shaved heads, are described as an “agwi army” that the reporter finds at the brink of death.27 The description assigns a strong image to the prostitutes possessed by agwi: although they are like walking dead, they are also animated by their anger at their unjust situation and are described as powerful. This report, however, is a rare account of agwi mobilization.

The frequent allusions to villages in the north of Korea and in Russia suggest the underlying transnational ideological configurations of the influence of the folk. An article in 1936 that was written about a murder in Majŏn-dong calls attention to the ways this fantastic agwi horror was dispersed across racial boundaries: the headline reads “Chinese man arrested, the agwi, a slave to carnal desires, murdered with a razor.”28 This description and the frequent allusions to remote villages suggest that the horror of the agwi not only resonated in the context of Korea, but is also often used in international encounters, indicating that the fantastic particularly is called upon in encounters with the uncivilized and unfamiliar. Although the starving ghost is often referred to in shaman belief as a facet of ancestral faith and memorial service, 29 the agwi that wreak havoc in the distant rural pockets of East Asia are not described with equal intimacy. The call for mobilization of troops to assist these isolated groups of people exhibits an extension of responsibility for these impoverished areas, but the writers of these reports are often reporting from the colonial urban centers, their views colored by certain prejudices about the remote northern regions.

22Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1 (1867), trans. Ben Fowkes (Middlesex: Harmondsworth, 1976), 342. 23Michael Pettid, “Shamans, Ghosts and Hobgolbins Amidst Korean Folk Customs,” SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies, no.6 (March 2009): 1. 24For more on Korean shamans and shamanistic rituals, see Laura Kendall, The Life and Hard Times of a Korean Shaman, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988). 25Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15(1): 11–40. 26“Sanxi Province Famine, Terrible Scenes of Flesh eating Cannibalism” (Hapsŏsŏng taegigŭn siginnyuk ch’amgyŏng), Tonga ilbo, August 24, 1929. 27“The Truth behind the Ch’ŏngjin Prostitute Strike: A Series of Questions and Answers with Rouge, a Prostitute” (Ch’ŏngjin e saenggin ch’anggi maengp’a chinsang ruju, ch’anggi wa ŭi ilmunil tapke sibilmyŏng i sanggŭm hangjaeng), Tonga ilbo, April 17, 1931 28“The Arrest of a Chinese man for the Murder of a Wife in Majŏn” (Majŏn e ch’amsŏltoen puin pŏmhaenghan Chunggugin ch’aep’o), Tonga ilbo, August 23, 1936. 29Although in a different context, Laura Kendall’s study on contemporary shaman practices and consumer culture was very helpful in understanding broadly how shamanism can mediate between past ancestors and present relationships with commodities. See Laura Kendall, “Of Hungry Ghosts and Other Matters of Consumption in the Republic of Korea: The commodity becomes ritual pop,” American Ethnologist vol. 35, no.1 (2008): 154–170.

Often times, as Lim points out with the example of ghost films, elements that are inconsistent or do not coincide with “modern homogenous time”30 are encoded in fantastical narratives. These fantastical narratives not only call attention to the nonsynchronous temporalities that are encoded within the “secular code”31 of modernity, but to the encoding process that often takes place within the visual and narrative ontologies under the project of modernity.32 In the case of colonial Korea, these projects of modernity are often implemented by the imperial state, and the forms mistaken for supernatural, premodern elements become seeds for anticolonial criticism.

The presence of these elements and the horror of starving ghosts in a projected seamless narrative of modernity reminds us of the importance of acknowledging varied cultural forms in the study of cultural history. By examining the constellation of media in the 1920s and 1930s, it is clear that the starving ghost is both a consistent reminder of the influence of folk beliefs and simul-taneously an important semiotic representation of the problems within Korean modernization and Japanese colonialism.

As Jean and John Camaroff have asked in their examinations of zombie culture in South Africa, what do monsters, zombies—or starving ghosts in this instance—have to do with their contemporary material realities? Reflecting on the present moment and the ubiquitous and stubborn cultural phenomenon of the zombie film, it is undeniable that ghosts play an important role in negotiating shifting social structures, their spectral presence often coinciding with and emerging at a junction of conflicting material and emotional realities: “an un-precedented mix of hope and hopelessness, promise and impossibility, the new and the continuing.”33 In many ways, though this study focuses on a little over a decade of cultural history during colonial Korea, more broadly it addresses a similar question about the role of specters in Korean cultural history and the contexts in which they are called forth. During this pivotal moment starting in the 1920s, the starving ghost correlates with the fear of being reduced to the living dead, describing the ontological experience of being left to die or emigrating in pursuit of employment. Like the zombie image that is a now familiar image of alienated labor, the starving ghost is just one of the apparitions that not only reminds us of this crisis in the countryside but also of the material meanings behind our images of horror.

30Lim, Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique, 12. 31Ibid. 32Ibid., 13. 33Jean and John Camaroff, “Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millenial Capitalism,” Codresia Bulletin ¾ (1999): 17–28.