One of the richest streams of research in joint venture (JV) studies has centered on parent control exercised over joint ventures (JVs). Recent work on how parent firms choose from among various control mechanisms (Kumar and Seth 1998; Barden

However, what is missing from these studies is an examination of the dynamic aspects of parent control in joint ventures. Chen

Parent control is defined as influence exercised by the parents over the JV’s management (Luo

Following the introduction, the bargaining power argument about the initial division of management control between the partners is reviewed. In the Hypothesis Development section, hypotheses associated with trust, capability change, and control change are developed. The research methodology is then discussed. The discussion of the results is presented in the final section of the paper.

According to the bargaining power argument, the MNE (multinational enterprise)’ s control over its foreign subsidiary is thought to be determined by the interaction between the MNE and its local counterpart. This argument was first applied to the bargaining situation between the MNE and the host government, primarily from less developed countries (LDCs) where the host governments were key stakeholders in foreign direct investment (FDI) negotiations (Gomes-Casseres 1989; Blodgett 1991; Yan and Gray 1994; Pan 1996; Brouthers and Bamossy 1997).

In such bargaining situations, the MNE usually possesses the capital, technology, management, and marketing skills needed to launch an FDI project successfully, while the host government has control over the access to its domestic market, natural resources, and other conditions for the successful operation of the MNE in its own country. To maintain economic independence from the MNE’s control over its domestic economy, the host government struggles with the MNE over the division of the JV's management control and the distribution of the payoffs from the joint venture. What determines the outcome of that struggle is thought to be the MNE's or the host government's bargaining power stemming from the asymmetric dependent relationship between the MNE and the host government. Therefore, the MNE’s achieved management control over its foreign subsidiary is hypothesized to be a reflection of the relative bargaining power between the MNE and the host government. It has been found that the most important source of the MNE’s bargaining power is technology, followed by financial resources and management expertise (Blodgett 1991; Pan 1996; Brouthers and Bamossy 1997).

The bargaining power argument has been further extended to the bargaining situation between an MNE and a local firm, excluding a host government from the negotiation over JV control (Yan and Gray 1996; Child

Using the initial resource contribution as a measure of the parent firms' bargaining power, previous studies succeeded in predicting the initial division of management control between the partners (Yan and Gray 1996; Child et al. 1997; Mjoen and Tallman 1997). Indeed, the resources contributed at the founding of the JV can have a lasting effect on the evolution of the joint venture. In their case study of four joint ventures between US and Chinese firms, Yan (1998) documents how well the initial balance of bargaining power is retained over time through continuous adjustment actions by both partners. Such adjustment actions occurred whenever the parent firms' relative bargaining power significantly shifted from its original state.

What the literature reviewed so far has in common is that they all limited their attention to the initial state of the bargaining power balance and the resulting division of management control between partners. However, as indicated by recent researchers (Inkpen and Beamish 1997; Cardinal

To completely examine the capability change-control change relationship, we incorporate "trust" into our research model. Trust is hypothesized as an antecedent of capability change. So the link "trust-> capability change-> control change" is examined as the complete research model of our paper.

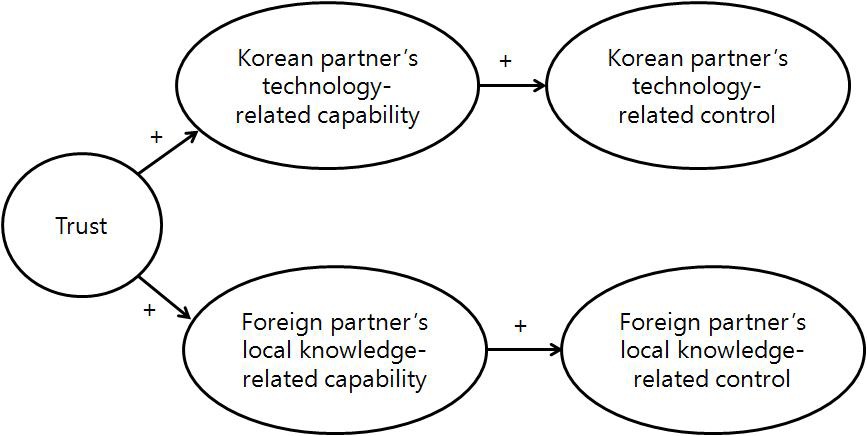

Figure 1 depicts this study's research model. The change in the existing division of management control is theorized as the result of a shift in the existing bargaining power balance between the joint venture partners. To capture the change in the amount of the joint venture partners' bargaining power, we measure the joint venture partners’ capability change. Trust is also examined as an antecedent of the joint venture partners' capability change. So the link "trust -> capability change -> control change" is examined in this paper.

Korea is a research setting where developed market partners and local Korean partners join forces to form JVs. Developed market partners typically contribute technology-related resources to the venture while local Korean partners contribute local knowledge-related resources. Technology-related resources that developed market partners contribute to the venture are defined as the ones employed to develop the JV's products and production processes. Such resources have been found to be those that local emerging market firms seek most when selecting developed country partners (Hitt et al. 2000, 2004; Lyles & Salk 2007). Local firms' needs for technology-related resources originate from a technology gap existing between developed and emerging market countries. Blodgett (1991) found that technology provides the most powerful leverage for developed market firms when they negotiate with local emerging market firms for the division of JV equity ownership. In contrast, developed market partners' major criterion for selecting local partners is whether local firms possess local knowledge-related resources that the developed-market firms lack (Hitt et al. 2000, 2004; Fang & Zou 2009). Developed market partners' needs for local resources is attributed to the context difference between developed and emerging markets, as advanced by resource-based theorists emphasizing the context-specific nature of rent-earning resources (Madhok 1996, 1997). The greater the difference that exists between the developed and emerging market context, the stronger will be the developed market firms' needs for local knowledge-related resources. In these cases, a local partner's firm-specific advantages are derived mostly from the local partner's knowledge of the local culture, customs, and market characteristics, from simply being an indigenous firm that enjoys preferential treatment by the local government or from its position in the local network of organizational relationships important to the successful operation of a business. Local knowledge-related resources are specifically defined as the resources that consist of local marketing skills, local personnel management skills, and local distribution channel management skills.

2. Trust and Capability Change

Trust between the JV partners is important in creating a foundation for learning. Without trust during the collaborative process, information exchanged between the partners may be low in accuracy (Currall and Judge 1995). Conversely, an atmosphere of trust should contribute to the free exchange of information between committed exchanged partners, because decision makers do not feel that they have to protect themselves from the others' opportunistic behavior (Blau 1964). This suggests that inter-firm trust is a key variable that determines knowledge accessibility. As trust develops over time, learning opportunities will increase and each partner will decrease their efforts to protect their knowledge and skills.

In fact, for the JV partner whose knowledge is being acquired, the risk of knowledge spillover exists. Knowledge spillover occurs when valuable firm knowledge spills out to competitors, who can then use the knowledge to gain a competitive advantage (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). When there is high inter-partner trust, knowledge spillovers are acknowledged to be an inevitable result of joint venture involvement (Inkpen and Currall 2004). Although a JV partner risks knowledge spillover, there is also the opportunity to capitalize on spillovers of the other partner's knowledge. Thus, firms may be able to learn more than they lose and build valuable learning ability in the process. In short, as inter-partner trust increases, partner willingness to provide access to information is likely to increase, thus providing the foundation for partner learning. For the local Korean partner who depends on the foreign partner for the JV's technology, the increase in a degree of trust between partners will increase the learning opportunities, thus leading to the increase in the Korean partner's technology-related capability. On the other hand, for the foreign partner who depends on the Korean partner for the JV's local knowledge, the increase in the degree of trust between partners will increase the learning opportunities, thus leading to the increase in the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability. The reasoning so far leads to the following hypotheses.

3. Capability Change and Control Change

Learning that involves the acquisition of partner knowledge can be a powerful basis for bargaining and JV control. Hamel (1991) argued that the bargaining power vested in a particular firm will almost certainly erode if its partner is more adept at learning the other’s skills or quicker to build valuable new competencies. According to the bargaining power theory that sees power as central to the relationship between the parties concerned (Thibaut and Kelley 1959; Michael 2000), the inter-partner capability transfer through learning triggers the change in the bargaining power balance between partners. In other words, the outcome of learning is the reduction of the dependence of one partner on the other for the operation of the JV. The reduced dependence, in turn, upsets the existing asymmetric dependence that shaped the original bargaining power balance. This newly shaped dependent relationship between partners increases or decreases the one or the other partner's bargaining power, which is eventually used to increase or decrease the control exercised over the JV's management. According to Hamel (1991), JV partners’ intents to exploit the increased bargaining power is important in leading to the increased control over the JV. For the hypothesis development, it is assumed that JV partners have the intention to exploit the increased bargaining power for the acquisition of control in the JV.

What if one partner refuses to accept the reality that the existing bargaining power balance between them has changed? In that case, trust between partners is likely to be damaged, thus leading to JV instability. Yan (1998) reports about a joint venture case in which the U.S. partner keeps proposing to add one more U.S. member to the venture’s board of directors to justify the U.S. firm’s increased bargaining power. The Chinese local partner’s refusal of the repeated proposal made the U.S. partner unhappy and eventually damaged the relationship between the partners. He further reports that “the unhappy U.S. partner eventually threatened not to renew its technology transfer agreement with the venture, and started creating a new venture with a different local firm.” Yan’s observation suggests that partners experiencing reduced bargaining power are forced to match the newly shaped bargaining power balance by giving up of some management control over the JV. The match thus achieved will, in turn, create a sense of equity and fairness that enhances trust between partners (Johnson

Based on the reasoning so far, we can expect that an increase in the parent firm's capability will lead to an increase in the parent firm's bargaining power, and then eventually an increase in the management control exercised over the JV. For the local Korean partner who depends on the foreign partner for the JV's technology, the increase in the local Korean partner's technology-related capability will increase the Korean partner's bargaining power in the area of technology, thus leading to the increase in the technology-related control exercised by the Korean partner over the JV. On the other hand, for the foreign partner who depends on the Korean partner for the JV's local knowledge, the increase in the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability will increase the foreign partner's bargaining power in the area of local knowledge, thus leading to the increase in the local knowledge-related control exercised by the foreign partner over the JV. The reasoning so far leads to the following hypotheses.

The data for this study were collected in 2010 through in-person, semistructured interviews with Korean general or deputy general managers of Korean-U.S., Korean-Japanese, or Korean-European manufacturing JVs. The 2010 edition of

As

To check the non-response bias, we compared the 51 responding firms with the 149 non-responding firms for the following three characteristics: foreign ownership (percentage), JV size (total capital investment), and JV age (number of years since foundation). The t-test results were all insignificant, indicating that there was no important non-response bias in our sample.

The sample distribution of the foreign parents’ nationalities closely follows the study population’s distribution. Parent firms from Japan made up 57.7 percent of the sample. The remaining sample was made up of parent firms from the EU (19.7 percent) and the U.S. and Canada (22.5 percent). JVs that were involved in the electric and electronic sector comprised 25 percent of the sample. The next most common sectors were machinery (21 percent) and chemicals (19 percent). This industry distribution also closely mirrors the study population’s distribution. Both industry and foreign parents’ nationality were controlled for in subsequent analyses.

1) Management control variables

For these measures, general managers were asked to evaluate the extent to which the Korean (foreign) partner has increased control (or influence) over each of the managerial activities over the last 5-10 years (1=no increase, 2=slightly increase, 3=medium increase, 4=significantly increase, 5=very highly increase). This five-point Likert-type scale represents the increase in the amount of control exercised by each partner over the JV’s management during the last 5-10 years.

2) Capability variables

3) Trust variables

Trust was measured with a five-point Likert-type scale adapted from Currall and Inkpen (2002). General managers were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement (1=Strongly disagree, 3=Neither disagree nor agree, 5=Strongly agree) with the following statements, given the partner-relationship that has been formed during the last 5-10 years:

The first of three items was a reverse statement which was reverse-coded so that higher scores represent higher levels of trust.

The partial least squares (PLS) technique was selected for the analysis of the causal modeling. PLS is an appropriate technique when sample sizes are small, when data normality and interval-scaled data cannot be assumed, and when the goal is the prediction of the dependent variables.

1) Measurement model: validity and reliability

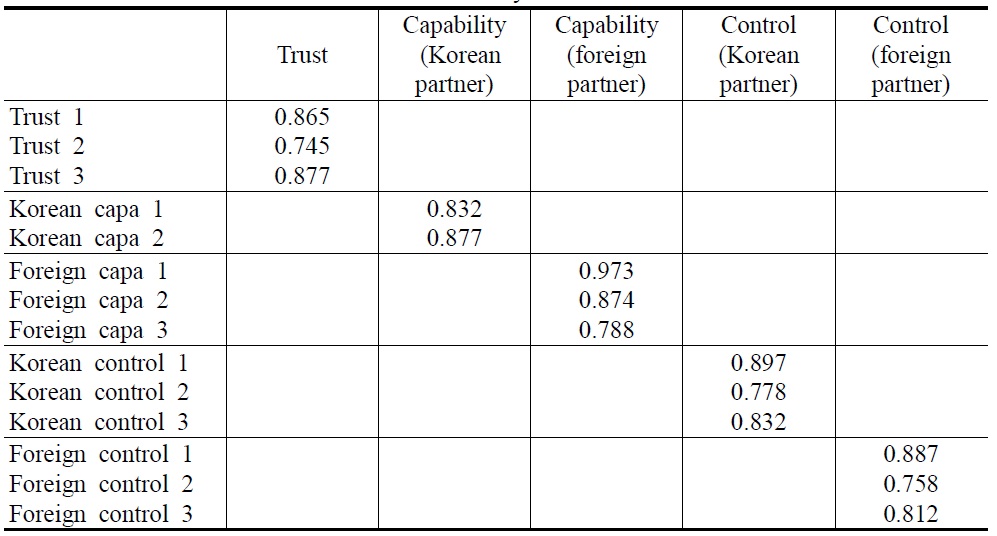

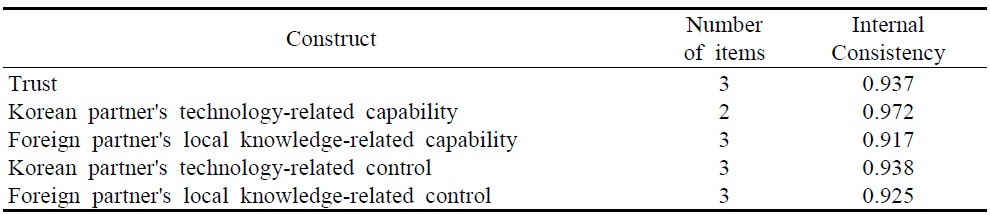

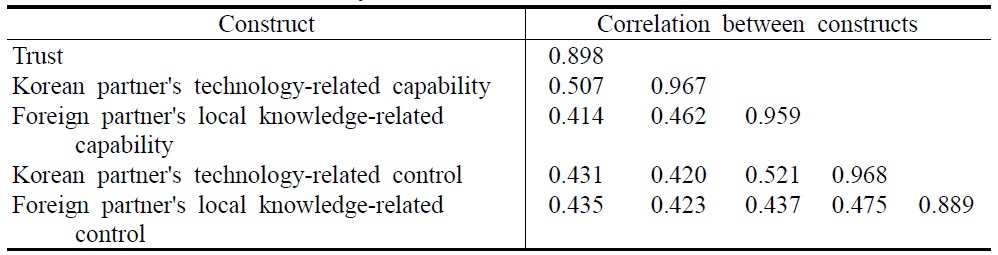

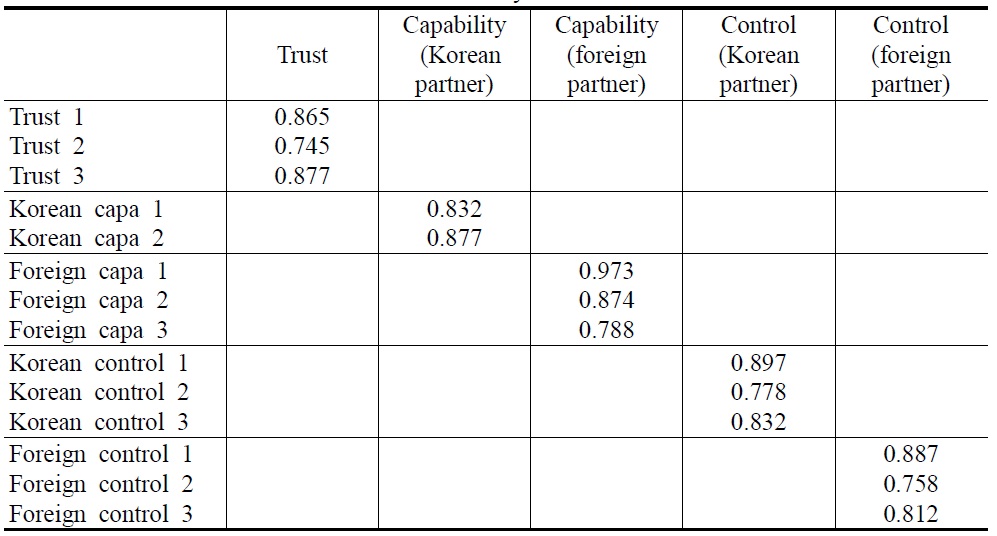

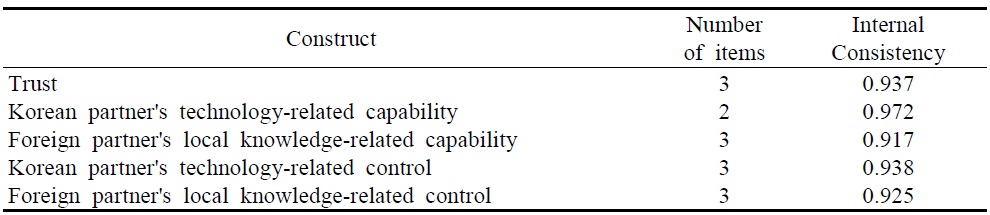

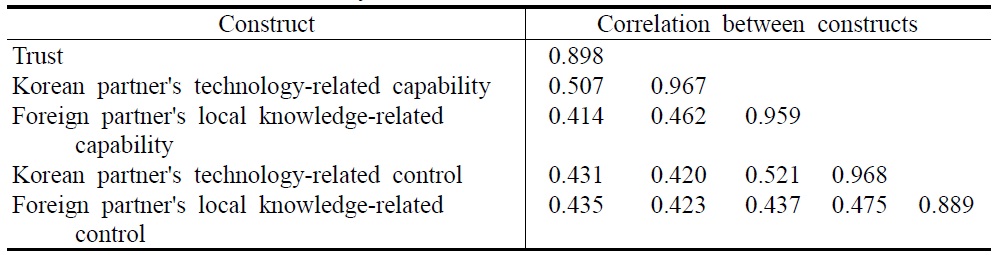

In assessing the measurement model, the principal concern was with the internal consistency and the reliability of the items in the multiple-item constructs. The reliability of individual items was determined by the inspection of item loadings on the respective constructs. In all cases, all individual items had a high degree of reliability as each loading exceeded 0.7 (Table 1). Convergent validity was assessed using internal consistency, a measure similar to Cronbach's alpha (Table 2). As reported in Table 1, all constructs had internal consistencies greater than 0.90, demonstrating strong convergent validity. Discriminant validity was gauged by comparing the correlation matrix constructs (Table 3). For each construct in Table 3, the diagonal elements (average variance extracted) were greater than the numbers in the associated row or column, suggesting a good discriminant validity. In other words, the correlations between constructs off the diagonal were smaller than the square root of the AVE (average variance extracted) on the diagonal.

[Table 1] Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis: Varimax Rotation

Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis: Varimax Rotation

Measurement Model

[Table 3] Discriminant Validity

Discriminant Validity

2) Structural model

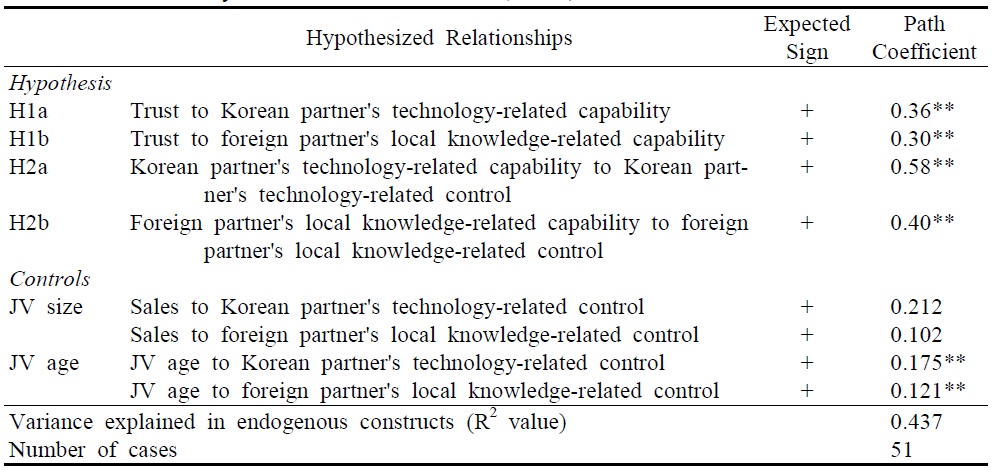

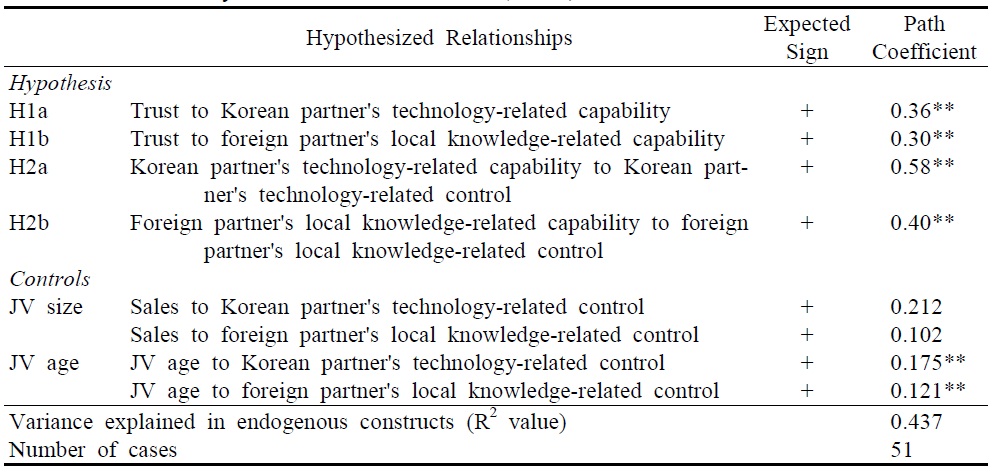

Given the adequacy of the measurement model, it is appropriate to proceed with interpretation of the structural model. Table 4 reports the outcomes of the hypothesis testing and the explained variance in the model's endogenous constructs. All of the study's four hypotheses were supported, and the model explained 43.7% of the variance in the control change of the joint ventures.

Hypothesis 1a predicted that trust between the partners is positively related to the Korean partner's technology-related capability. Consistent with the prediction of Hypothesis 1a, the positive significant path coefficient on Trust in Model 1 indicates that an increase in the degree of trust between the partners will lead to the increase in the Korean partner's technology-related capability. Hypothesis 1b predicted that trust between the partners is positively related to the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability. Consistent with the prediction of Hypothesis 1b, the positive significant path coefficient on Trust in Model 2 indicates that an increase in the degree of trust between the partners will also lead to the increase in the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability.

[Table 4] Summary of the Path Estimates (N=51)

Summary of the Path Estimates (N=51)

Path coefficient testing Hypothesis 2a, showing that the local Korean partner's technology-related capability is positively related to the local Korean partner's technology-related control, was found to be significant. This suggests that an increase in the local Korean partner's technology-related capability will eventually lead to the increase in the local Korean partner's technology-related control exercised over the JV. Path coefficient testing Hypothesis 2b, showing that the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability is positively related to the foreign partner's local knowledge-related control, was also found to be significant. This suggests that an increase in the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability will eventually lead to the increase in the foreign partner's local knowledge-related control exercised over the JV.

As for the control variables, JV age was positively related to the Korean partner's technology-related control and foreign partner's local knowledge-related control, while JV size was not related. The significance of JV age suggests that the older JVs become, the more change in control happens between the partners.

This paper extends the study of parent control exercised over a JV’s management by examining what causes the existing division of management control between partners. The change in the existing division of management control was theorized as a result of a shift in the existing bargaining power balance between partners. To capture the change in the amount of the joint venture partner's bargaining power, we measured the joint venture partner's capability change. To completely examine the capability change-control change relationship, we incorporate "trust" into our research model. Trust was hypothesized as an antecedent of capability change. So the link "trust-> capability change-> control change" was examined as a complete research model of our paper in the context of international joint ventures in Korea.

Trust between partners was found to be positively related to both the Korean partner's technology-related capability and the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability. In other words, it was found that the increase in the degree of trust leads to the increase in both the Korean partner's technology-related capability and the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability. This finding suggests that trust is the foundation for learning from the partner. When trust is low, learning cannot happen properly in the joint venture. Low degrees of trust lead to the fear of opportunism, thus increasing the perceived need for protection against the other partner's opportunistic behavior. In such a situation, the free exchange of information or knowledge between partners is severly limited, thus leading to a low level of learning as well as joint venture instability. Low levels of learning cannot create both partners' capability change.

Technology-related and local knowledge-related capabilities were found to be positively related to technology-related and local knowledge-related control. In other words, it was found that the increase in the technology-related and local knowledge-related capabilities led to the increase in the technology-related and local knowledge-related control, respectively. The finding suggests that, in the case of joint ventures between developed market firms and local Korean firms, the foreign partners contributing technology to the venture are likely to lose their power and the resulting management control over the JV's technology to the local Korean partner. Likewise, the local Korean partners contributing local knowledge-related capabilities to the venture are also likely to lose their power and the resulting management control over the JV's local knowledge to the foreign partners.

This study has some limitations that future research needs to address. The first concerns the small sample size of the study. Because this study adopted in-person interviews as the research method, we could not collect a large size of sample. So, in order to further validate this study's findings, future research needs to conduct a study using a larger size sample.

A second limitation is the generalizability of the findings. This study examined international joint ventures(IJV) in Korea. Based on this, the interpretation of the findings should be limited to the IJVs in Korea only. This study should be replicated in other countries to generalize the findings.

This study has added to our understanding of the dynamics of parent control. As expected, the local Korean partner's technology-related capability is linked to the local Korean partner's technology-related control, and the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability is related to the foreign partner's local knowledge-related control. The more the local Korean partner's technology- related capability increases, the more likely that the local Korean partner's technology- related control increases. Likewise, the more the foreign partner's local knowledge-related capability increases, the more likely that the foreign partner's local knowledge-related control increases. Trust was also found to facilitate an increase in both partners' capabilities through learning.