There is a growing consensus that the regulation of nuclear waste management of alpha or beta decay nuclides such as 129I has to be emphasized, and that a selection basis has to be made in terms of a disposal program of nuclear waste generated from a nuclear power plant and other nuclear facilities [1].

Recently, in Korea, an analytical method development for alpha and beta emitters has been conducted with regard to the regulation of transportation or the disposal of nuclear waste generated from nuclear power plants. One of these critical nuclides is 129I, which is produced by nuclear fission in nuclear reactors, and has a long half-life (t1/2=1.57 × 107y) [2]. The importance of the control of this nuclide has been recognized, owing to its radio-ecological effect [3,4].

129I, however, is difficult to measure directly with a beta counter due to its very low specific activity of (6.4 Bq/μg) [5].

Generally, concentration of difficult-to-measure (DTM) radionuclides, such as 129I, contained in nuclear wastes generated from nuclear power plants can be predicted from the scaled factor (129I/137Cs, 129I/60Co) by measuring the radionuclide instead, such as 60Co, 137Cs which are relatively easier to measure.

Therefore, the activity of 129I has to be measured accurately in order to calculate the scaling factor (radioactivity ratio of 129I and 137Cs) in relation to the activity of the standard nuclide. The latter will then be used as described above. However, the radioactivity ratio of 129I to 137Cs varies widely, owing to many different classes of radioactive waste forms generated from nuclear power plants. Consequently, it can be concluded that a trustworthy chemical analysis is required to determine the characteristic scaling factors for each plant [7,8].

Iodine is volatile and it can be easily lost during the solvation or recovery process, since the oxidation process of I2 to IO3- is slower that the production reaction of I2 from an I- solution. D. Geithoff et al. [9] reported the iodine behavior in the nitric acid matrix and suggested a fast oxidation procedure of iodine into IO3- with nitrosylchloride produced from the mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids. L. C. Bate et al. [10] showed the oxidation reaction of I2 into IO3- with NaClO in an alkali matrix.

H. Kamioki et al. [11] reported the separation process of iodine from a 99Mo solution by collecting an I2 with 2 M NaOH after the oxidation process of I- to I2 using hydroperoxide in a 3 M Sulfuric acid matrix.

Katagir and Narita [12] put the environmental sample containing iodine into a quartz tube in advance of the combustion process at high temperature. The volatile iodine was collected on an activated carbon column and analyzed quantitatively by eluting it with a 20 % NaOH solution.

Xiaolin Hou et al. [13] washed the samples with a KHSO3 solution of 0.5 M and distilled water to measure the iodine content in natural water and seawater. I2 and I- were then separated from the other interfering ions using an anion exchange resin column (AG1x4, Cl-form).

In this report, the simulated concentrated liquid waste was prepared for the measurement of the radioactivity of 129I present in the primary coolant of the pressurized-water reactor [14,15]. The radioactive iodine tracer (125I, t1/2= 60.14d) was added into the simulated solution, and the recovery rate was measured to establish its analytical procedure. In addition, the chemical recovery rate of iodine during the extraction and stripping process was obtained to compensate for the final recovery rate loss of the whole process.

The purpose of this report is to provide a reliable analytical technique by reducing any possible source of error or uncertainty in the measurement of 129I in the primary coolant of a pressurized-water reactor.

Analytical grade reagents were used for KI and KIO3 (Aldrich Incorporated, 99.9 %). Standard radioactive iodine (NaI/0.1 M Na2S2O3, 10 × 105 Bq/mL, made by U.K) and 125I were used as a tracer for the verification of the recovery rate for iodine. The anion exchange resins (AG 1x2, 50-100 mesh, Cl- form, Bio rad co.) were used after washing with distilled water. A low energy photon spectrometry (LEPS) Ge detector system (model GLP 36,360/13P4, AMETEC) was used for the measurement of 125I.

2.2.1 Separation Procedure for the Non-radioactive Iodine

1,000 mg of NH2OH·HCl was added as a reducing agent into a glass vial (25 mL) containing 50 ug/ mL of KIO3 to reduce the iodate ion(IO3-) into iodine(I2). The acidity of the solution was then controlled with nitric acid to maintain the range of 0~1.6 M. The iodine in the solution was then extracted into an organic layer (CHCl3) and transferred into a glass vial. 5 mL of aqueous 0.1N NaHSO3 was added into the organic solution for further back-extraction of the iodide (I-). The aqueous layer was then separated after shaking for 3 minutes, and 1 mL of the aqueous layer was finally transferred for an ion chromatographic measurement, and the experimental condition was shown in Table 1.

2.2.2 Measurement Procedure for Iodide using 125I tracer

297.0 Bq of 125I as a radio-isotopic tracer was added into 10 mg/ mL of a KIO3 solution in a plastic vial (25 mL).

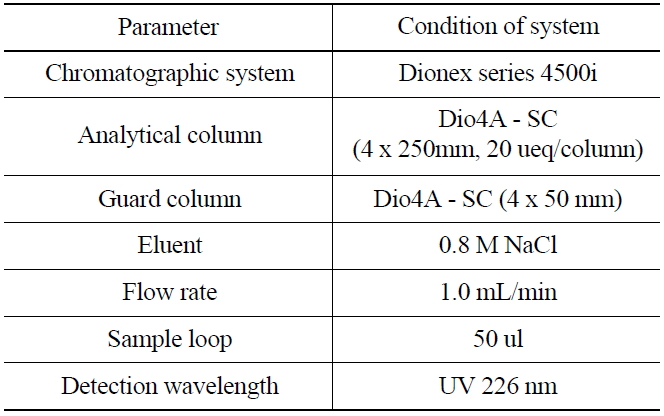

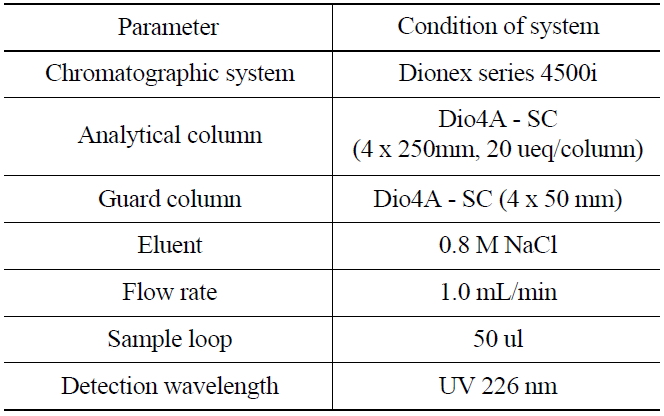

[Table 1.] Ion Chromatographic Conditions for the Analysis of Iodide

Ion Chromatographic Conditions for the Analysis of Iodide

1.6 mL of 5.0 M HNO3 and 1,000 mg of NH2OH·HCl as a reducing agent were added into the solution, which was shaken for 2 minute. 10 mL of CHCl3 was then added into the solution as an organic phase for the solvent extraction. After shaking for 5 minutes, the organic and aqueous phases were collected respectively into separate vials. 5 mL of 0.1 N NaHSO3 was added into the organic layer for back-extraction for 5 minutes. After back-extraction, the aqueous layer was collected, and 1 mL of 0.1 M AgNO3 was added to convert the iodide ions into a precipitate form. The precipitate was left to stand for 5 minutes at 70℃ and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The precipitate was transferred to a planchet for low energy photon spectrometry, and the activity was then measured with a low energy photon spectrometer for 10,000 seconds.

2.2.3 Absorbed Experiment of Iodine According to the pH Change of the Anionic Resin

10 mL of a sample, 5 mL of a phosphate buffer solution (pH 7) and 20 mL of distilled water were added into a plastic beaker containing 5.0 g of the anion exchange resins (AG 1x2, 50-100 mesh Cl- form). The resin solution was prepared and allowed to stand for 12 hours to wait for complete absorption into the resin. Next, 10 mg of KI were added to the solution, and the resin was transferred into a plastic column(length=15.0cm, and φ=0.8 cm.

20 mL of a 10 % NaClO solution (oxidant) passed through the column, and the same procedure was repeated 4 times. The eluent was then collected in a vial, 1.0 mL of 1.0 M HNO3 was added, and finally, the reducing agent (1000 mg, NH2OH·HCl) was added into the eluent solution.

After the solvent extraction procedure was conducted with separatory funnel in which 10 mL of CHCl3 contained was shaken for 3 minutes, the organic phase was separated and collected in a vial. After adding 10 mL of the 0.1 N-NaHSO3 solution into the separated organic phase, the solution was back-extracted to the aqueous phase. A precipitate formed by 0.1 M AgNO3 in an aqueous phase went through an aging process for 5 minutes at 70℃. After the centrifuging process, the final sample was now transferred to a planchet, and dried below 70℃. Its activity is measured for 10,000 seconds with a low energy photon spectrometry system.

3.1 Optimum Chemical Conditions for the Separation and Recovery of Non-radioactive Iodine

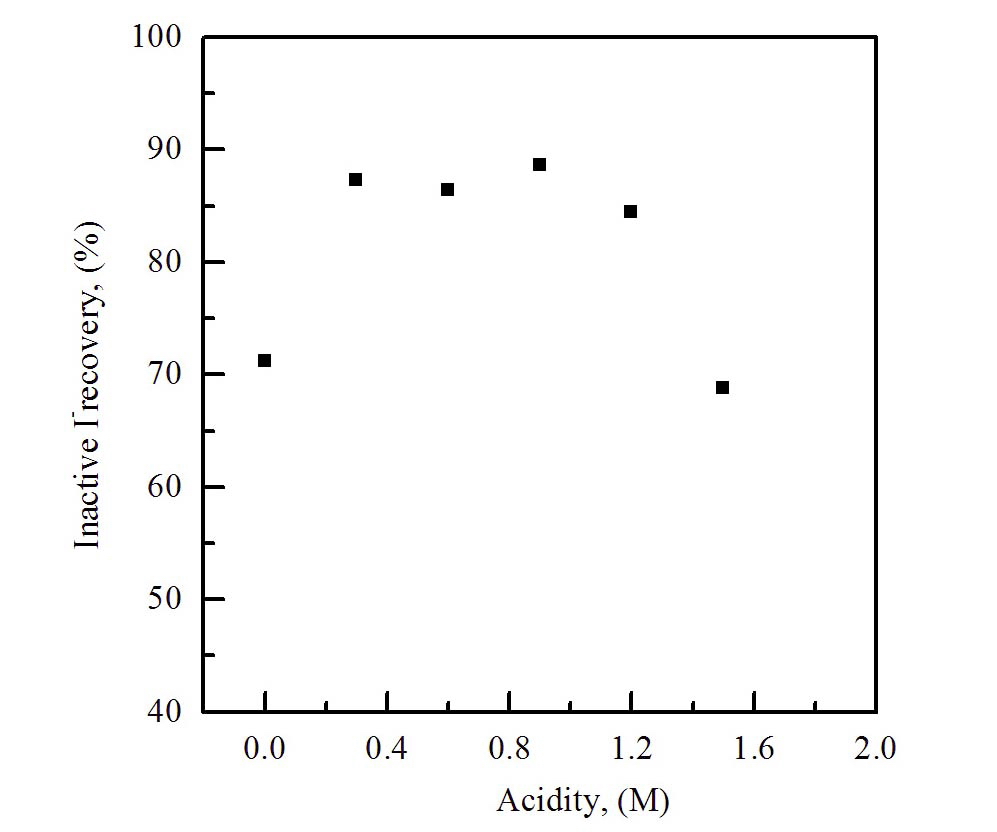

The recovery rate of iodine as a function of acidity (on the variation of pH in the eluent) was measured to find the optimum chemical conditions for the separation of non-radiative iodine. The recovery rate of iodine was measured, while the acidity of the sample was controlled in the range between 0.0 and 1.6 M.

Fig. 1 shows the results of the optimum concentration of the acid for the extraction process with an organic solvent. The concentration range between 0.4 and 1.2 M provides the highest recovery rate, and the NaClO solution was used as an eluent to extract the iodine absorbed on the anionic resin. This may be due to the oxidation of iodide ions, under the high acidity condition, to non-volatile oxy-iodate such as IO3- or IO4-, which are not extracted into the organic layer.

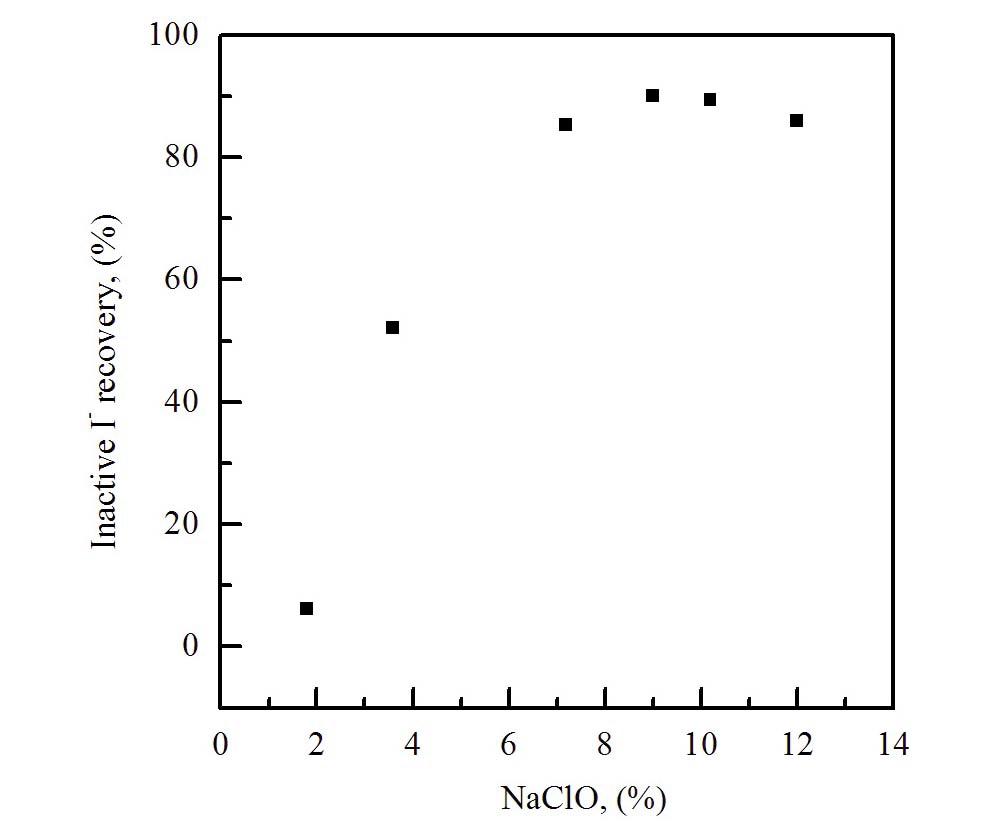

Fig. 2 shows the analytical results of the effect of the eluent concentration in the range of 2.0~12.0 % on the iodide recovery, using a column elution method. As shown, the concentration range of 8~10.0 % for NaClO was found to be suitable for the best elution of iodide from the anionic column.

3.2 Effect of pH on the Adsorption and Separation of Iodide on the Anion Exchange Resin

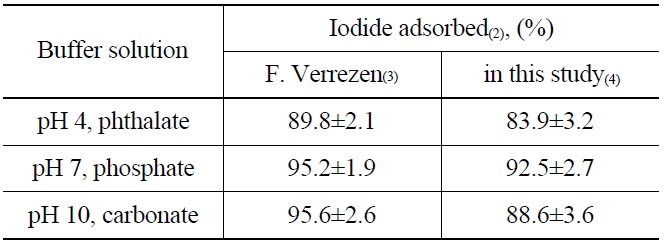

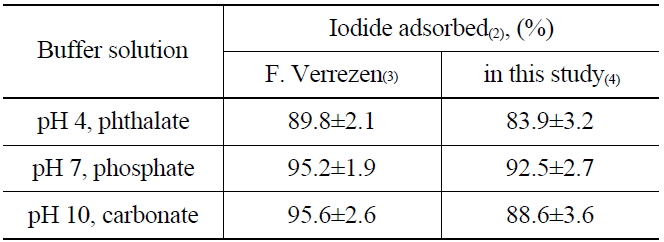

To understand the elution process of iodide ions on the anionic exchange resins (AG 1 x2, 50-100 mesh Cl- form), the adsorption rate of iodide was measured by soaking the resin in buffer solutions of pH 4 (phthalate), pH 7 (phosphate), and pH 10 (carbonate). The buffer solutions contain 125I as the tracer of the radioactive iodine, and KI as a carrier of 129I. The I- absorbed on the anionic exchange resin could be oxidized to the nonvolatile products, such as IO3- or IO4-, by NaClO during the elution process. The nonvolatile oxidation products are then eluted easily from the resin (AG 1 x2, 50-100 mesh Cl- form) owing to their relatively low affinity compared with other anions such as Cl-, Br- and NO2-, HSO3-, and NO3-. After adding the NH2OH.HCl and the reduction, the I2 remaining in the elution solution was extracted by adding organic solvent (CHCl3) and then back-extracted with NaHSO3 to an aqueous layer in the form of I- to determine the recovery rate. The adsorption results of the iodine using three different buffer solutions are shown in Table 2. The recovery rate found in this study was in the range of 83.9~92.5 %, which is closely similar to the previous report [15] as well as the results of adsorption yields at a higher pH than 7.

[Table 2.] Adsorption of Iodide on Anion Exchange Resin(1)

Adsorption of Iodide on Anion Exchange Resin(1)

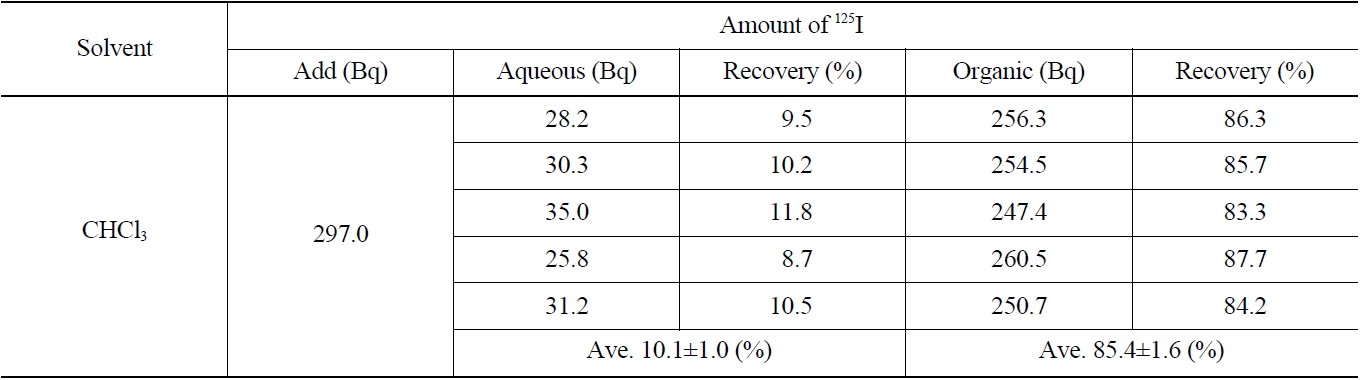

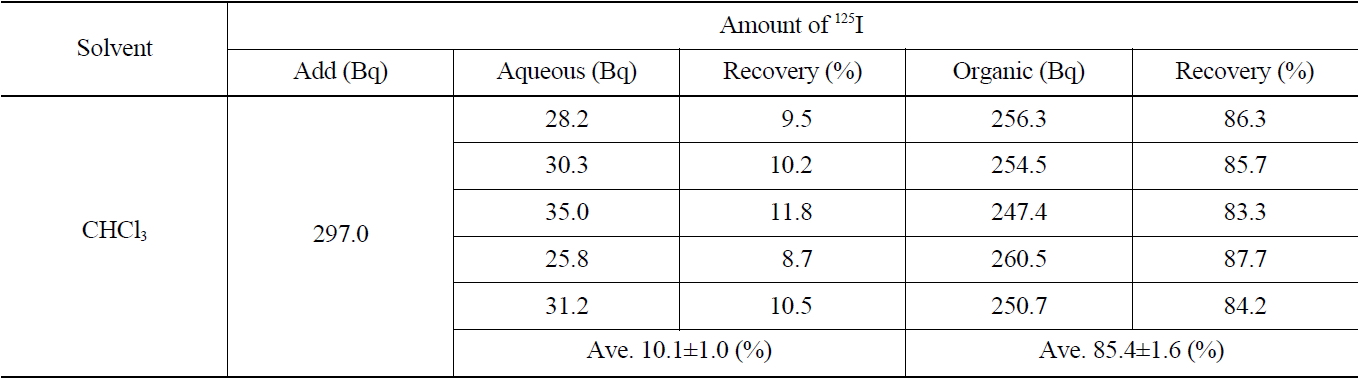

[Table 3.] Recovery of Iodide on the Extraction with CHCl3 (IO3 → I2)

Recovery of Iodide on the Extraction with CHCl3 (IO3 → I2)

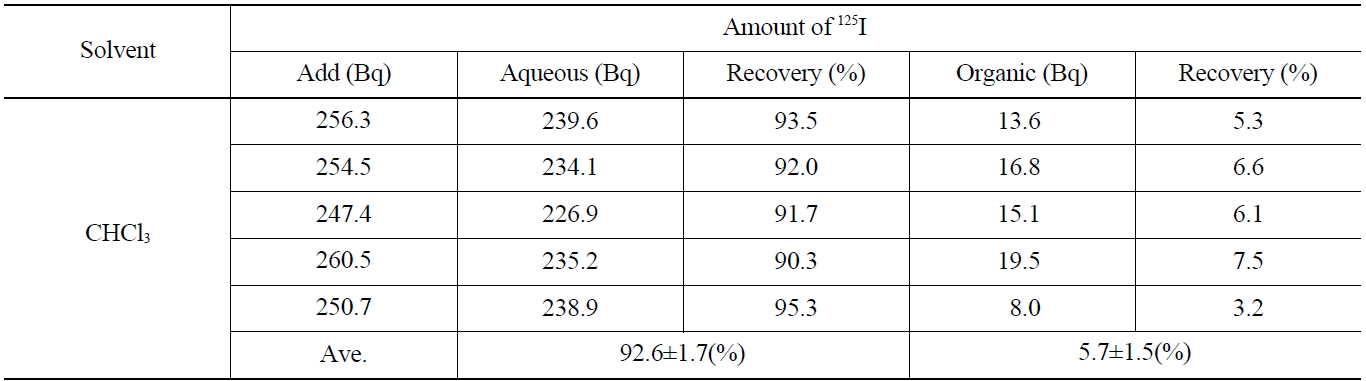

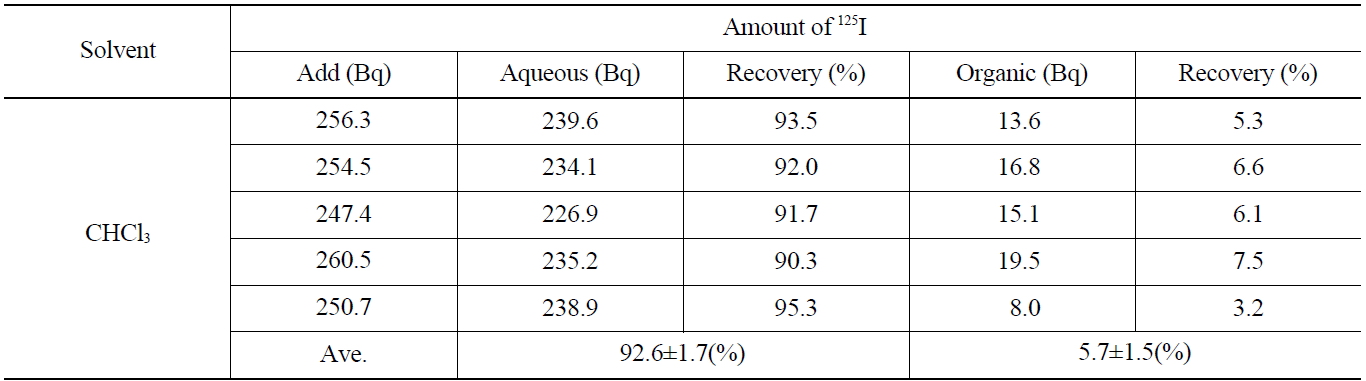

[Table 4.] Recovery of Iodide on the Back Extraction with NaHSO3 (I2 → I-)

Recovery of Iodide on the Back Extraction with NaHSO3 (I2 → I-)

3.3 Recovery Rate of Iodide by Stage using 125I Tracer

Several stages of the separation process including oxidation, adsorption, elution, reduction, and extraction, were required to analyze quantitatively the iodine present in a concentrated liquid waste sample. Some contents of the iodine can be lost through various separation processes of physical or chemical reactions owing to its high volatile property. In this study, the recovery rate of iodine for each separation process was measured using a radioactive iodine isotope tracer (125I) added into the starting sample at the initial step to compensate for the calculation of the total recovery rate of iodine.

The results of the radioactivity measurement of 125I after separating the organic and aqueous phases are indicated in Table 3. The average values of recovery of 125I in both the organic and aqueous phases were found to be 85.4±1.6 % and 10.1±1.0 %, respectively.

Table 4 shows the results on the recovery rates of I- in the aqueous phase after adding the 0.1 M NaHSO3 and stripping the I2 contained in the organic phase. As shown in Table 4, the iodine of the aqueous layer and organic layer showed up as 92.6±1.7 %, and 5.7±1.5 %, respectively. The overall recovery rate was found to be 98.3 %, in which the loss of 125I (1.7 %) was probably due to its volatility the back-extraction process.

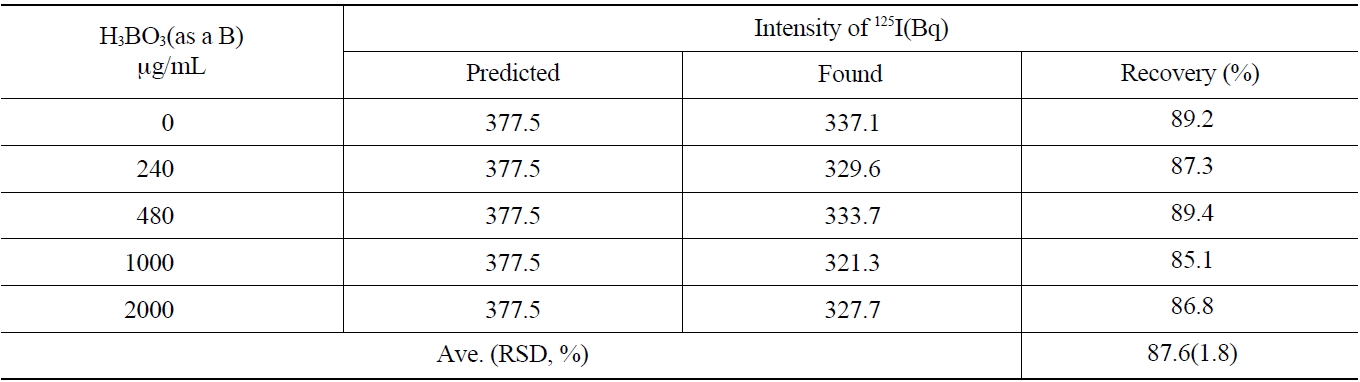

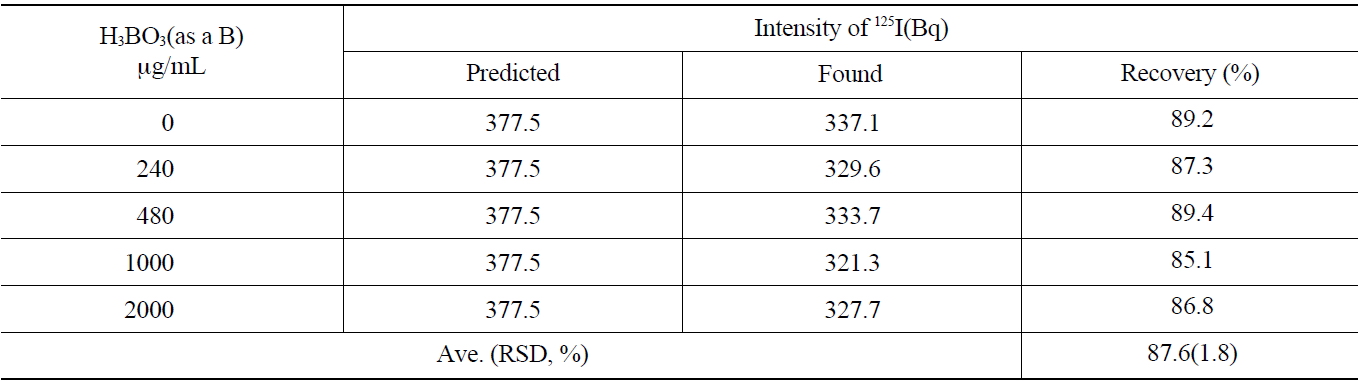

The primary coolant of a nuclear power reactor and concentrated liquid wastes contain a large amount of boron. The effect of the concentration of boron on the recovery rate of the iodine during the separation process was studied. The concentration range of 0~2,000 μg/mL of boron was selected to simulate the primary coolant of the pressurizedwater reactor and applied to the anionic exchange resins (AG 1x2, 50-100 mesh Cl- form). As shown in Table 5, the average recovery yield of iodine was found to be 87.6 ±1.8 % with various concentrations of boron.

As the results of this study show, a boron concentration of lower than 2,000 μg/mL in the primary coolant did not induce any problems for iodine recovery or separation.

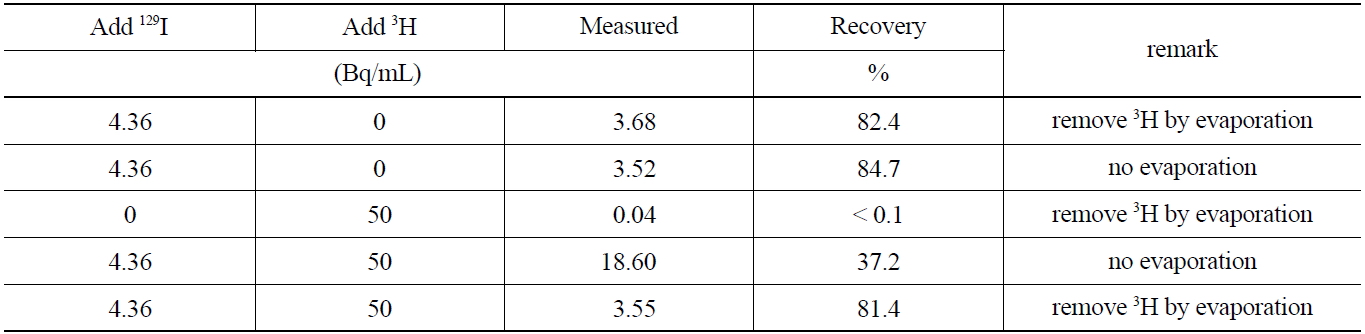

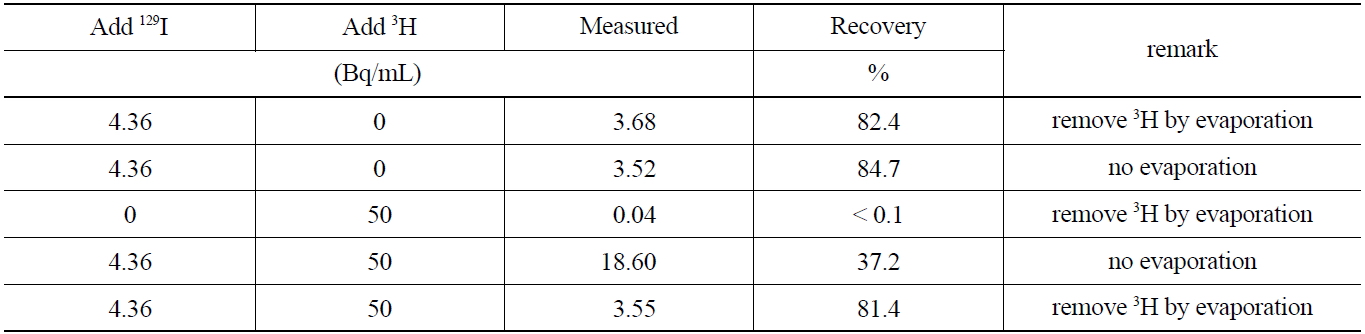

3.5 Effect of 3H on the Measurement of Iodine

Liquid radioactive waste produced in a nuclear power plant may contain high activity concentrations of 3H, which can be several orders of magnitude higher than that of iodine. Therefore, the effect the simultaneous presence of a beta emitting nuclide such as 3H, which is not separated and remains with iodine during the pretreatment procedure of the sample, has on the measurement of 129I activity was

Analytical Results of 125Iodide in Simulated Primary Coolant by Column Extraction Method with Adsorption of 125I on Anion Exchange Resin*

[Table 6.] The Interference of 3H in the 129I measurement*

The Interference of 3H in the 129I measurement*

studied. Furthermore, the removal of 3H by evaporation at temperatures below 70℃ after stripping the iodine form in the organic phase to an aqueous phase, was investigated. The activities of 129I before and after removing 3H are compared in Table 6which shows, the evaporation procedure for 3H, did not lead to any losses of 129I by co-evaporation effects. The comparison of the recovery rate results of the sample containing 129I indicates that the coexisting beta emitting nuclides such as 3H can effectively be removed through an evaporation procedure of the aqueous phase after the striping procedure, thus eliminating interferences in the low energy level spectrometry measurements

An analytical procedure and a chemical separation technique were studied for the quantitative determination of 129I, which is classified as a difficult-to-measure(DTM) nuclide. The recovery rate was measured by adding 125I as an iodine tracer to the simulation sample to measure the activity concentration of 129I in a pressurized-water reactor primary coolant. The optimum condition for the maximum recovery yield of iodine on the anion exchange resins (AG1 x2, 50-100mesh, Cl- form) was found to be pH 7. The effect of boron content in the pressurized-water reactor primary coolant on the separation process of 129I was investigated, as was the effect of 3H on the measurement of iodine activity. The results show no influence of the boron content, nor of the 3H was found at activity levels lower than 50 Bq/mL for 3H, and for concentrations of boron of less than 2,000 μg/mL .