The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine (CUMC) was founded in 1954. CUMC had maintained discipline-oriented basic medical courses for 55 years. In 1973, instructional objectives for basic medical education (BME) were formulated according to each discipline. Although the learning objectives were rigorously reviewed and revised to accommodate changes in society and the education environment thereafter, the discipline-oriented structure of BME courses was maintained. The BME courses consisted of 3 semesters of basic medical sciences, 2 semesters of clinical sciences, and 3 semesters of clinical clerkship.

During the medical education reform in 2009, the discipline-oriented BME structure was abandoned and body systems were chosen as the main structure of BME courses. During the reform, learning objectives were shuffled and converted to competency-based learning outcomes. Since then, we have run the new BME courses for 5 years and an evaluation of the new courses has been recommended. BME courses can be evaluated in many different ways. Among them, we decided to analyze the courses in terms of learning outcomes. We wanted to know whether the coverage, repetition, and omission of the learning outcomes were appropriate for national and global standards. In addition, we wanted to check whether the medical students who successfully finished our BME courses met the assessment items of the medical licensing examination by evaluating the learning outcomes.

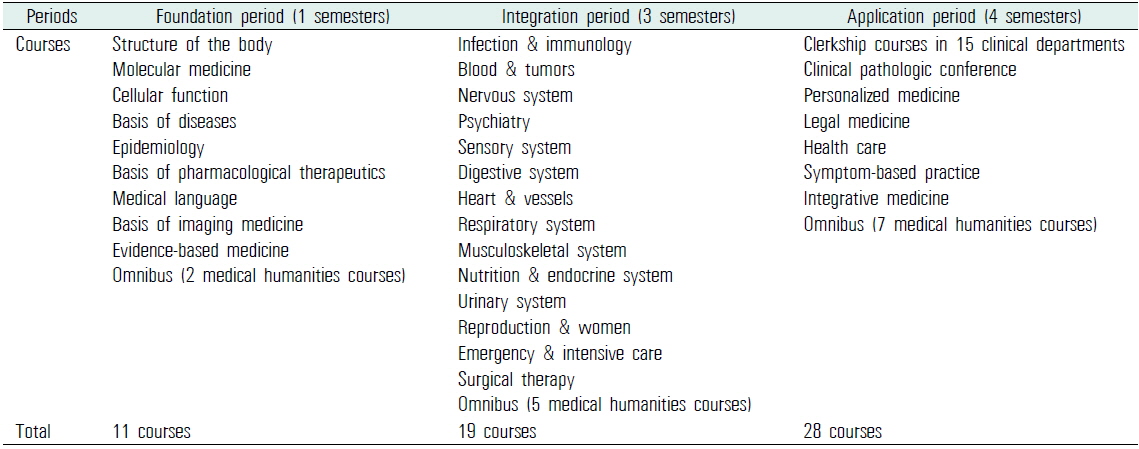

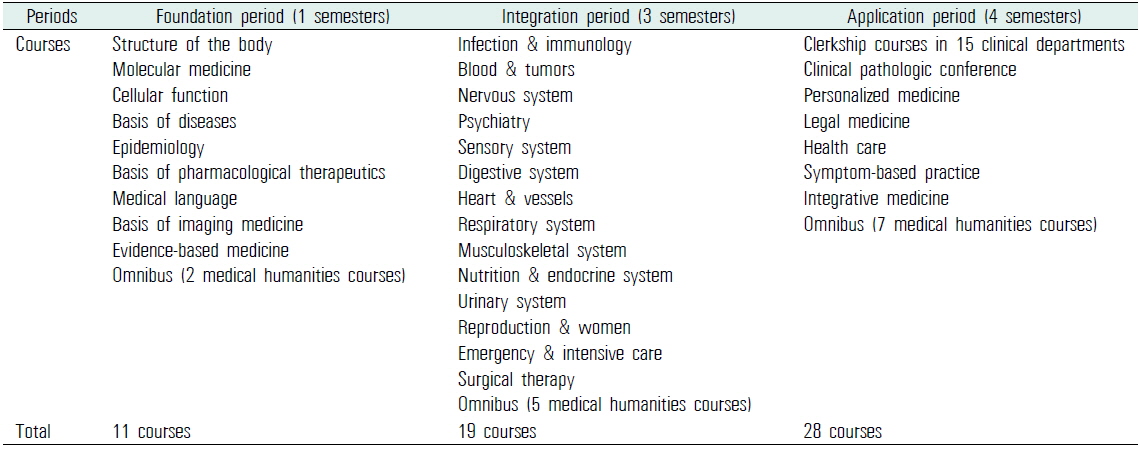

The current 4-year BME courses in CUMC consist of 3 sequential periods: the foundation, the integration, and the application. The foundation period mainly consists of basic medical sciences, such as anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry. In the integration period, students take multidisciplinary courses structured by body systems. For example, in the infection and immunology course, the education contents related to the topic were delivered to the students through lectures on several related disciplines, such as microbiology, immunology, internal medicine, and pediatrics. The application period is mainly composed of a 2-year clerkship in the affiliated hospitals (Table 1).

[Table 1.] Basic medical education courses in the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine

Basic medical education courses in the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine

Recently, the National Health Personnel Licensing Examination Board (NHPLEB) in the Republic of Korea published a set of assessment items based on 105 physician encounters (PEs) for the medical licensing examination. NHPLEB’s assessment items are competencies required of medical graduates to achieve physician licensure. Because NHPLEB’s assessment items are structured by PEs, which are different from the structure of the learning outcomes in CUMC, we need a systemic method to cross-reference the two different systems. Because the collection of learning outcomes from all BME courses is complex and huge, standardization is required for a comparison to different systems. With the standardization, it may be possible to compare and benchmark any kind of BME outcome, such as the outcomes from other countries (Elizondo-Montemayor et al., 2007) and global standards (Schwarz and Wojtczak, 2002).

In this study, we cross-referenced our learning outcomes with NHPLEB’s assessment items by building a relational database. We evaluated the coverage and consistency of our learning outcomes. Further, we found drawbacks and the need for revision of our learning outcomes to meet the nationwide requirements.

We chose 2 criteria to classify learning outcomes and assessment items of any kind. The first one is the PE. The PE is a commonly used item in a number of systems of learning outcomes (Prasad, 2010). Clinical presentations (CPs) (Mandin et al., 1995), which are another frequent type of learning outcome, can be covered by PEs. To formulate the final list of PEs, we reviewed 105 PEs of the NHPLEB and 179 CPs of the Medical Council of Canada (MCC) (Baumber et al., 1992). Eighty-six items were found in both the lists. After combining the items of NHPLEB and MCC, we added 16 PEs of our own to meet all learning outcomes of CUMC. The final list had 214 PEs.

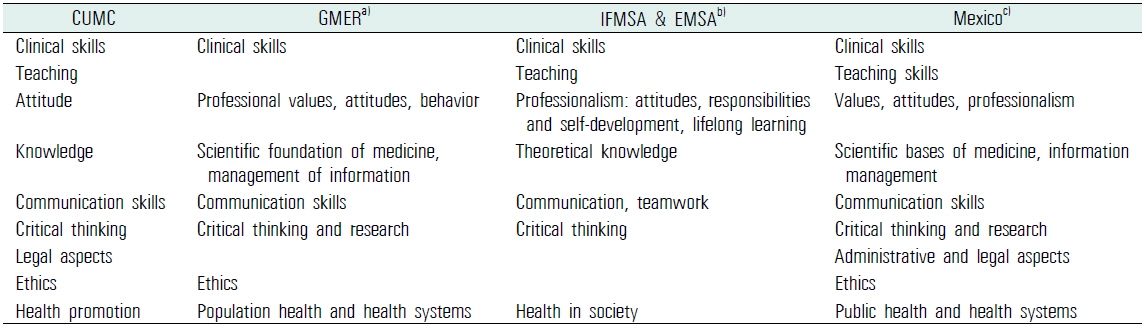

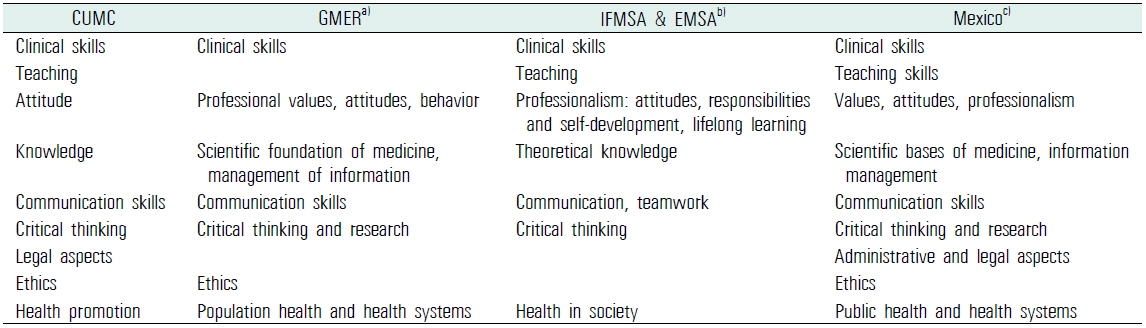

For the fine mapping of learning outcomes, we chose outcome domains as the second criterion to tag learning outcomes. We reviewed the articles on learning outcome domains (Elizondo-Montemayor et al., 2007; International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations et al., 2007; Schwarz and Wojtczak, 2002). The outcome domains introduced by previous articles were similar to each other. We compared the domains and finalized 9 domains that were mentioned in several articles (Table 2).

[Table 2.] Cross-reference of learning outcome domains found in articles and CUMC

Cross-reference of learning outcome domains found in articles and CUMC

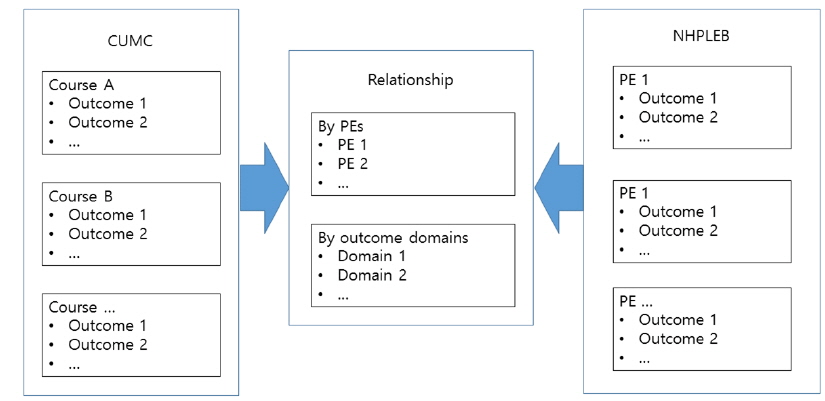

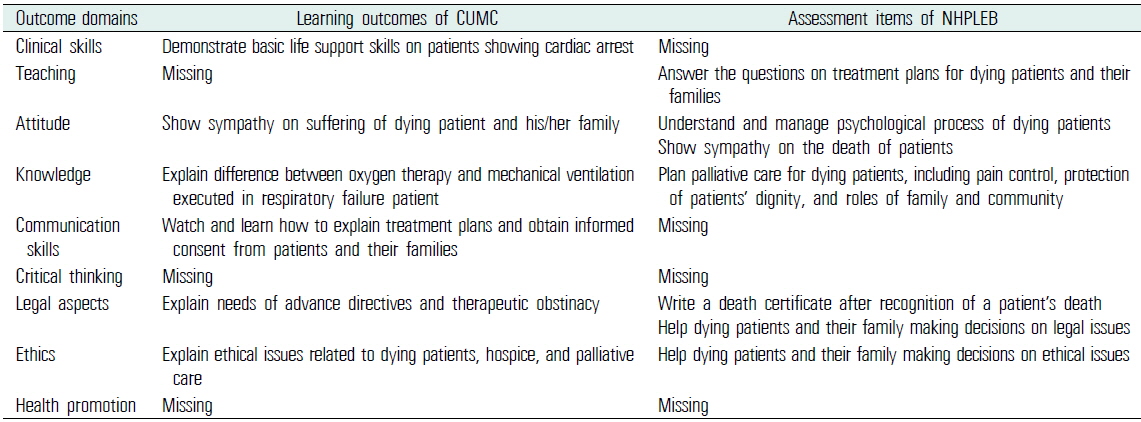

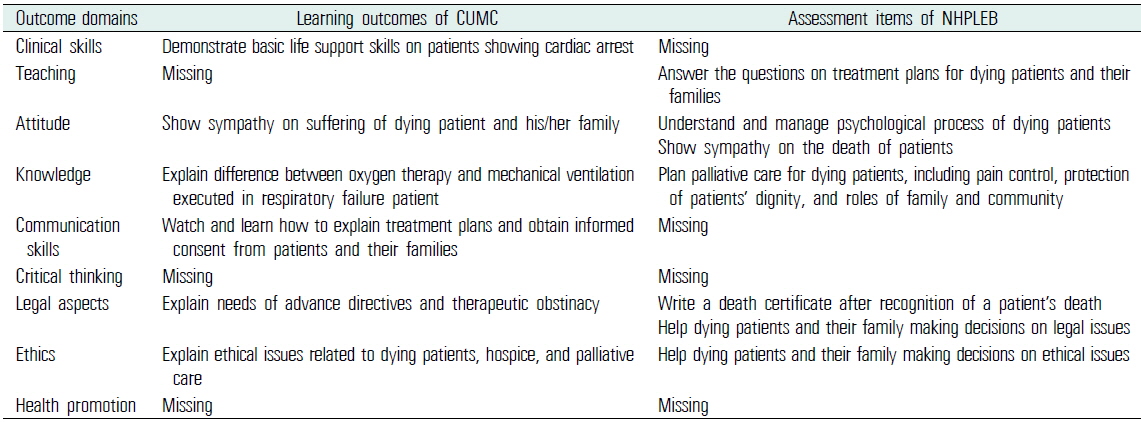

We collected 3,017 learning outcomes from all BME courses in CUMC and manually tagged each learning outcome with the 2-way categories mentioned above (Figure 1). The same tagging procedures were carried out with 608 assessment items by the NHPLEB. After the categorization of all outcomes, cross-referencing was performed in terms of the PE category and the outcome domain category (Table 3). Manual review and curation of the huge collection of learning outcomes and assessment items was a labor-intensive task. For a systematic approach, maintenance of data integrity, and further evaluation, we built a relational database populated with the learning outcomes, the assessment items, and their relationship using FileMaker Pro 13 (Santa Clara, CA, USA).

An example (physician encounter: dying patient & bereavement) of mapping learning outcomes of CUMC and assessment items of NHPLEB

1. Comparison of outcome domains

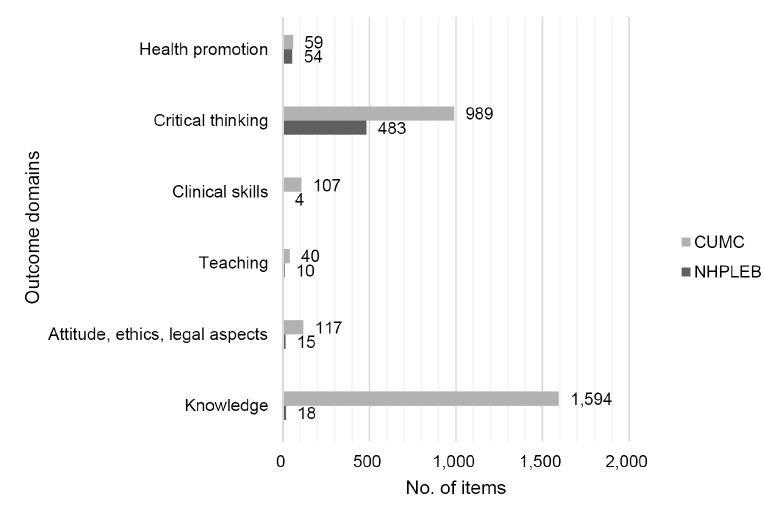

The assessment items of the NHPLEB and the learning outcomes of CUMC were categorized by outcome domains, and the number of lists in each domain was compared (Figure 2). Compared with the assessment items of the NHPLEB, the learning outcomes of CUMC were found to have considerably more emphasis on the knowledge domain. About half of the learning outcomes (1,594 outcomes) were categorized into the knowledge domain. We found 2 reasons for the propensity of CUMC’s outcomes to fall in the knowledge domain. Most of the learning outcomes (1,096 outcomes) of basic medical sciences were associated with the knowledge domain. Because the NHPLEB does not have an examination for basic medical sciences, the paucity of outcomes in the knowledge domain may be justified. In addition, a significant number of the outcomes in the knowledge domain did not state student competencies. We assumed that some of the outcomes were neglected in the process of conversion from instructional objectives to learning outcomes during the period of medical education reform.

Scarcity of the NHPLEB’s outcomes in the clinical skill and communication domains may be explained by the fact that the NHPLEB’s assessment items were intended for written examinations. The NHPLEB has a separate examination for evaluating clinical skills.

2. Comparison of physician encounters

Among 214 PEs, we found that 2 PEs (sexual violence and family violence/abuse), which were recently introduced in the assessment items, were not covered by the learning outcomes of CUMC.

3. Revisiting physician encounters with different levels of learning outcomes

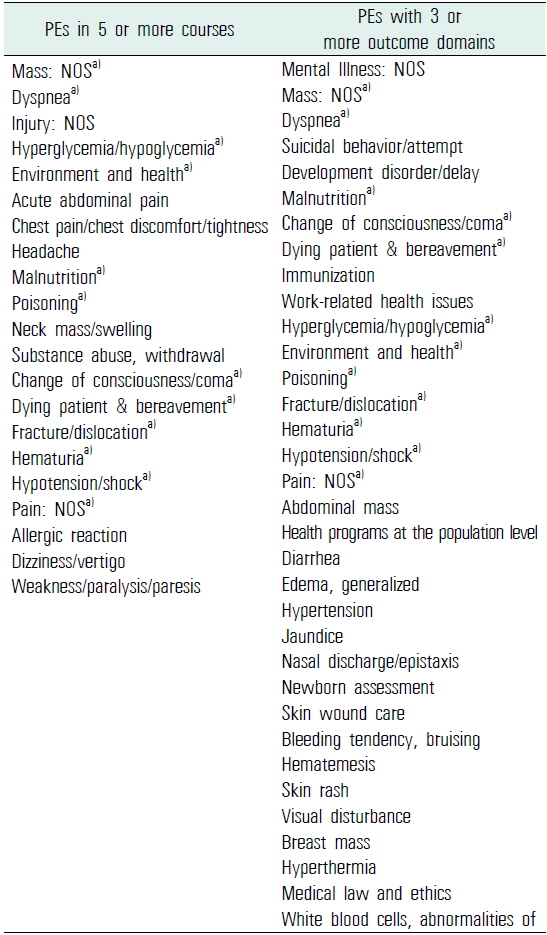

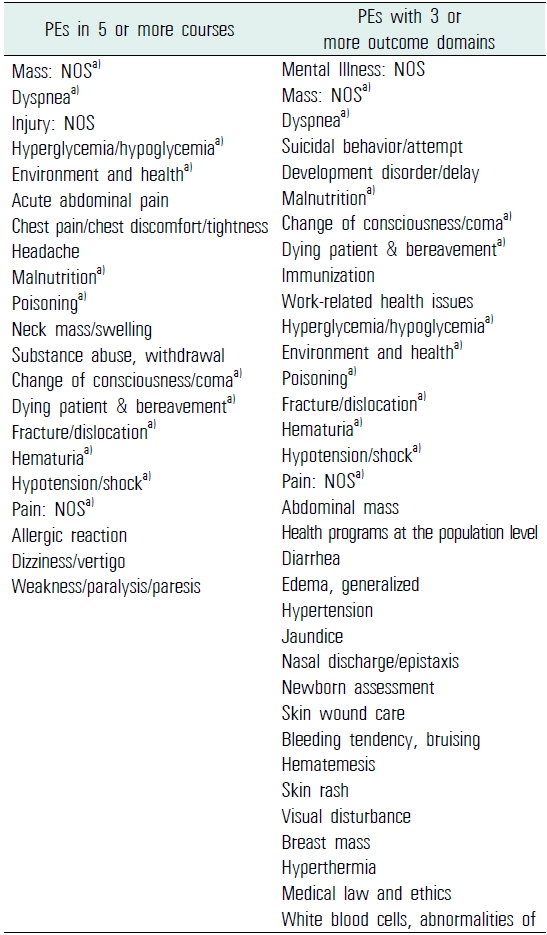

According to Miller’s pyramid, a clinical assessment has 4 levels (Miller, 1990). Although knowledge is required to show clinical competence, it is not enough to show clinical competence by itself. To build clinical competence on each PE, we need to revisit the same PEs with different outcome levels. To evaluate the revisiting schemes in CUMC’s learning outcomes, we counted the numbers of associated domains and BME courses for each PE across all BME courses. Among the 214 PEs, 82 PEs were associated with more than one outcome domain and 96 PEs were covered in more than one BME course. 21 PEs were repeated in 5 or more courses and 34 PEs had outcomes categorized into 3 or more domains (Table 4).

The lists of frequently covered PEs in basic medical education courses of the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine (in order of frequency)

We showed that allocating a PE and an outcome domain to each learning outcome and assessment item, respectively, facilitated the evaluation of BME courses in CUMC. Through the 2-way categorization of the outcomes, we could easily measure the concordance between the learning outcomes and the assessment items. Moreover, identification of the learning outcomes that were replicated in several courses was possible through the categorization process.

Each course in BME needs to be monitored and audited. The courses receive feedback from the faculty and the students, and we vigorously evaluate the feedback and actively adopt the feedback that has reasonable justification. Because the courses keep changing each education year, the balance of the whole education system can easily become unbalanced without any monitoring and auditing. Some faculty and medical students are concerned that the education of the basic medical sciences is not sufficient at CUMC. By analyzing learning outcomes, we were able to list contents on basic medical sciences in the BME program and further adjust the appropriate amount of basic medical science education in the body-system-oriented courses.

The abovementioned mapping practice can be extended to the area of student examinations. Besides the evaluation of courses, the 2-way categorization may facilitate the evaluation of the examinations that the medical students take during the courses. As we did with learning outcomes, each test item can be tagged with a PE and an outcome domain. Medical students’ competencies on associated learning outcomes can be evaluated by analyzing the difficulty level of the test items. By collecting test results and the associated learning outcomes on each student, we may provide the students’ individual portfolios on competence. With information on the level of a student’s achievement, we can provide individualized self-directed learning modules to students who have a low profile in a certain group of learning outcomes.

Only 4 assessment items of the NHPLEB were included in the domain of clinical skills. Because the current cross-referencing of learning outcomes and assessment items was confined to a written examination, most clinical skills were not covered in this study. Currently, we are planning an extension of the outcome analysis system to accommodate OSCE/CPX (objective structured clinical examination/clinical performance examination) and the clinical skill examination of the NHPLEB. This will complete the evaluation process of concordance between the learning outcomes and the assessment items.

By evaluating the courses and outcome domains associated with the same PEs, we could see the repetition and deepening of the learning outcomes. As the students advanced to the next level of courses, the same PEs were introduced again along with learning outcomes with different categories of outcome domains. With this repetition and widening of the associated outcome domain, students may consolidate the competencies related to each PE.

In summary, cross-referencing 2 different structures of learning outcomes and assessment items can be achieved by building universal criteria. We showed that a 2-way categorization (PEs and outcome domains) could be applied to body-system-oriented learning outcomes and PE-structured assessment items. Through the mapping process, we were able to evaluate the coverage and the repetition of the learning outcomes of the BME courses in CUMC. The mapping results will be used as valuable evidence to guide the management of BME courses.