Many studies in economic and cultural sociology have highlighted critics as a major influence in the field of cultural products (Baumann 2001, 2002; Boatwright, Basuroy, and Kamakura 2007; Caves 2000; Griswold 1987; Hirsch 1972; Levy 1979; Shrum 1991, 1996; Sochay 1994; Hsu 2006a, 2006b; White and White 1992). In particular, a growing body of researchers has examined the process in which film critics affect other market actors. Films are cultural products with a high level of uncertainty about their quality in the market context (White 2001), so audiences tend to rely on film critics to reduce their uncertainty about a film before deciding to consume it (Podolny and Hsu 2002).

For example, Shrum (1991) and Baumann (2002) claim that film critics, as cultural mediators, potentially influence the perception and behavior of other market actors such as audiences and distributors, and they also participate in the formation of cultural hierarchy through the critical discussion process. Hsu (2006a) and Hsu and Podolny (2005) argue that the primary goal of film critics is to establish the standards for other market actors who try to assess the value of film products. More specifically, studies conducted by Sochay (1994) and Boatwright et al. (2007) show that critics’ favorable reviews positively influence the box-office performance of films. Allen and Lincoln (2004) find that the retrospective consecration of American films is affected by the discourse produced by film critics. As shown in the literature mentioned above, film critics serve as key players in the film market, providing audiences with general information about a film (e.g., characters and plot) and the criteria for evaluating the quality of the film in question.

Despite abundant research on the role of film critics as influencers or mediators, however, much less attention has been paid to the way in which film critics guide audiences to a better understanding of foreign films. In particular, most studies on the role of critics in the film market have been limited to studies on U.S. films. It is easy to hypothesize that foreign films offer greater uncertainty to the U.S. audiences than domestic films due to language barriers and cultural unfamiliarity. Thus, it would be interesting to examine the unique ways by which critics attempt to introduce foreign films to the U.S. market and influence U.S. audiences’ understanding of foreign films.

While the role of film critics including that of film guides and evaluators can vary depending on the interests and needs of the primary audience (Hsu and Podolny 2005), this study limits its focus to the guiding role of film critics by investigating the ways in which they enhance the general U.S. audiences’ comprehension of Asian films. More specifically, we are interested in the “comparison strategies”—comparing a foreign film to other domestic and foreign films released to the market in the past—that film critics employ in their reviews to help audiences improve their understanding of Asian films. Towards this end, the

Asian Films in the United States: A Brief History

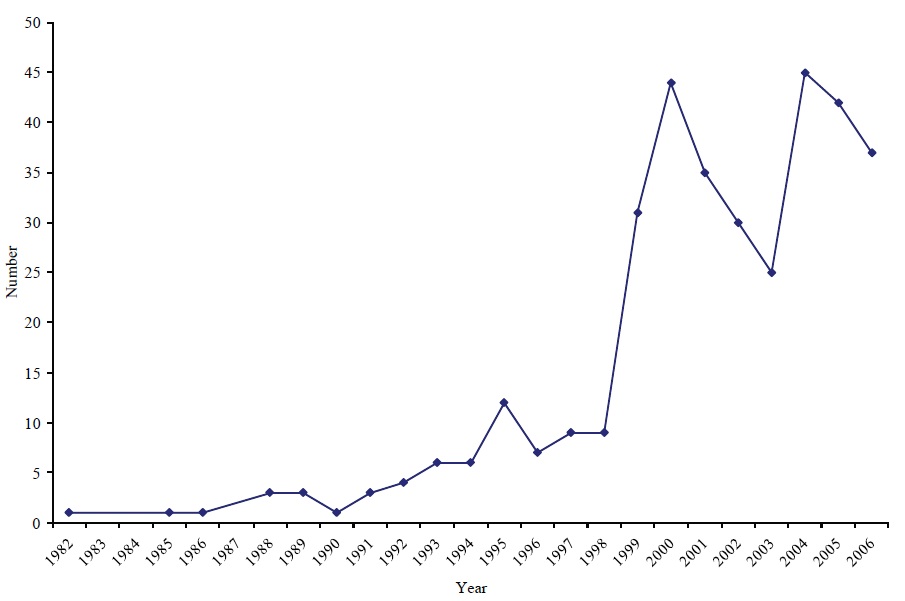

In recent years, the presence of Asian films in the United States has dramatically increased (cf. Sklar 1994, 2002; Su, Kim, and Hong 2007). This phenomenon, which the media sometimes exaggeratedly terms as an Asian “invasion,” is very new, but introduction of Asian films to the United States dates way back to the 1950s. In our study, an Asian film is defined as a film produced in an Asian country (or Asian countries) with a predominantly Asian language dialogue track, directed by a filmmaker (or filmmakers) of Asian descent, for primarily domestic Asian audiences (sometimes also global audiences);1 Asian countries include East Asia (e.g., Japan, China, and Korea), Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand and the Philippines), South Asia (e.g., India and Nepal), and West Asia (e.g., Iran). Figure 1 presents the yearly number of Asian films released in the United States during the period from 1982 to 2006.

The first wave of Asian films in the United States began with Japanese and Indian films in the 1950s. Akira Kurosawa’s

Since the late 1980s, the number of Asian films in the United States has gradually increased with the introduction of Pan-Chinese films (Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese films) and Iranian films. For example, in 1988, two Chinese films—Chen Kaige’s

Since 2000, many Asian countries have actively participated in the global film market, and, as a result, more diverse Asian films have circulated in U.S. theaters. Korean films have been introduced to the United States since 2000 with the release of Jang Sun Woo’s

Overall, Asian films have increased dramatically in the United States around the turn of the 21st century with a much larger number of films, greater diversity in the number of countries where the films were made, and greater impact on the American film industry. Many Asian films released in the United States were awarded prizes or nominated for prizes at major film festivals; moreover, some of these Asian films including Hong Kong films or Chinese films achieved huge commercial success in the United States. As a result, the increasing presence and popularity of Asian films in the United States exerted greater influence on Hollywood’s production style as well as American audiences’ perception of Asian films and Asian culture.

1Our definition of Asian film is based on the criteria used by the Academy of Motion Picture Art and Science (for foreign language films:http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/rules/rule14.html) and the San Diego Asian Film Festival (https://www.withoutabox.com/03film/03t_fin/03t_fin_fest_01over.php?festival_id=1422).

U.S. Critics and Their Comparison Strategies

Through our perusal of Asian film reviews that have appeared in the

In this study, we classify comparison strategies used by critics in their review of Asian films into three categories, depending on the comparison counterparts: U.S. comparison (comparing to U.S. counterparts), foreign comparison (comparing to counterparts from countries other than the U.S. and the focal Asian country that is compared), and home comparison (comparing to counterparts from the same Asian country). Each comparison is further broken down to film comparisons, director comparisons, and actor/actress comparisons. According to our survey of film reviews in the

U.S. comparison refers to comparing Asian films/directors/actors/actresses under review with their American counterparts. For example, in his

For comparison of actors, Stephen Holden (1996), in his review of

Foreign comparison refers to comparison between an Asian film/director/actor/actress under review and their counterparts from various countries other than the United States and the focal Asian country that is compared. For example, to compare films, Janet Maslin (1994) introduces

Similarly, Elvis Mitchell (2000) introduces a Hong Kong director, John Woo, to discuss the talent of a Korean director, Lee Myung-Se, in his review of

Home comparison includes comparison of films, directors, and actors/actresses from the home country of the film under review. For example, A. O. Scott (2002) compares

As for comparison of directors, Dave Kehr (2003) reviews the Japanese film

For comparison of actors, Elvis Mitchell (2000) mentions a Japanese actor, Toshiro Mifune, as a reference of comparison to show the changing images of another Japanese actor, Takeshi Kitano:

Given the existence of information asymmetry between producers and customers, and the latter’s uncertainty on the quality of the former, consumers tend to either rely on signals of producers’ qualities such as status (Podolny 2005) and reputation (Fombrun 1996) or count on knowledge and guidance from information agents (Eisenhardt 1988; Mishra, Heide, and Cort 1998). These agents are required to devise various tactics to deliver information on the producer to the customer (i.e., the principal) in an effective and efficient way. Comparing a producer to other producers who are already familiar to the customer serves as a way by which customers can be quickly informed of the producer’s values and haracteristics, although this diffusion process may not be free of the agent’s bias.

In the film industry, critics take on the role of information agent by introducing a film to the market audiences along with their own description and evaluation of its features and qualities (Baumann 2002; Podolny and Hsu 2002; Shrum 1991). Moreover, as discussed above, critics definitely utilize comparison tactics in their review of Asian films, directors, and actors/actresses, which probably help facilitate audiences’ understanding of those films. Critics’ use of such a comparison strategy is probably more prevalent for Asian films than for American or other Western films in the U.S. market because U.S. consumers feel more uncertain about Asian films. However, our reading of critics’ reviews shows that not all reviews include a comparison strategy, indicating that some reviews involve a greater demand for a certain type of comparison strategy than other reviews. In this study, an attempt is made to explore sources of such variance by focusing on some features of Asian films and the historical context of those films in the U.S. market. More specifically, we propose that the extent to which a certain type of comparison strategy (U.S. comparison, foreign comparison, and home comparison) is used in film reviews is affected by film genres, multiplicity of genres, prior release of films form the home country in the U.S., and recency of a film.2

It is well known that consumers’ acceptance of products from foreign countries varies, partly depending on the compatibility of the products with the value and belief systems of the home country. Such compatibility is particularly imperative in the film industry because a film is deeply embedded in cultural meaning, reflecting the writer’s view of life, the director’s imagination, and the actors’ (actresses’) interpretations (Craig, Greene, and Douglas 2005). Neelamegham and Chintagunta (1999) further suggest that variance in cultural compatibility is also derived from different film genres because certain genres are more culturally embedded than others.

For example, Hollywood comedies do not travel well because many components of comedy are closely related to language, that is, “short circuits between signifier and signified,” and especially, laughter is heavily connected to the “unspoken assumptions that are buried very deep in a culture’s history” (Moretti 2001). By contrast, action films travel relatively well through the dismissal of language which is a major cultural component (Hall 1976), replacing it with other expressions such as explosions or screams. Accordingly, strongly culture-bound genres are less successful in crossing national boundaries than culture-neutral genres (Craig et al. 2005).

Given the crucial role of culture in product compatibility across national boundaries and the close link between culture and film genres, we suggest that culture-bound genres are more likely to lead critics to make comparison of films, directors, or actors/actresses from the same country. However, their strong culture-oriented characteristics will make it difficult for critics to find the counterparts of comparison from countries outside the home country. In contrast, culture-neutral genre films will be more likely to induce U.S. or foreign comparison than culture-bound genre films. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Extending the theory of organizational niche width by Hannan and Freeman (1977), Hannan, Pólos, and Carroll (2007) formulate the consequences of product categories for audience expectation and market performance. One of their key arguments is that products spanning multiple categories lack representativeness in any one of their relevant categories and, thus, tend to suffer from a lack of identity. A set of economic sociologists lends empirical support to the liability of multi-category membership in their studies of the film industry, showing that films spreading over multiple genres are likely to be judged as having less authentic identity and inferior quality than those categorized into a single genre (Hsu 2006b; Hsu, Hannan, and Koçak 2009; Zuckerman and Kim 2003).

While membership with a single category enhances the strength and distinctiveness of product identity, single-category products have less “niche overlap” with other products than do multi-category products (Baron 2004; Hannan, Pólos, and Carroll 2007), thus hurting their comparability with other products in the market (Zuckerman et al. 2003). For example, films belonging to a certain single genre tend to be regarded as distinct and distant from other films, whereas multi-genre films are considered to have weaker boundaries with other films. This indicates that multi-genre films are more open to diverse interpretations and evaluations from audiences than singlegenre films. Thus, critics will find it easier to find comparison counterparts for Asian films, directors, or actors/actresses of multi-genre films than singlegenre films, regardless of whether they are compared with U.S., home, or foreign counterparts. Therefore, the second hypothesis is as follows:

>

Prior Release of Home Films in the U.S.

Critics’ comparison strategy will also be affected by the extent to which films from the home Asian country have previously been released in the U.S. market. If there is a large enough pool of reference films from a home country, critics will be equipped with a greater set of films to consider for home comparison. Moreover, greater cumulative number of films from a home country will make it less necessary for critics to draw U.S. or foreign comparison, given that home films usually allow a greater level of comparability. Therefore, the third set of hypotheses is:

Since World War II, United States has played a predominant role in leading the global cultural field, including literature and cinema (Janssen, Kuipers, and Verboord 2008). When it comes to cinema in particular, the United States has taken the principal position in facilitating globalization of film production and film distribution. Most major film producers and distributors are concentrated in the United States, resulting in the convergence of global film production toward Americanization. And as the sian film industry has grown in the global market, it has been increasingly influenced by Hollywood in various ways as reflected in the term, “Hollywoodization” of Asian films (Klein 2004; Rampal 2005). This trend may suggest that recent Asian films in the United States are more comparable with the U.S. or foreign counterparts, such that more recently released Asian films are likely to lead critics to consider more U.S. or foreign comparison but less home comparison. Therefore, we hypothesize:

2Note that we do not consider the three comparison strategies mutually exclusive such that critics’ use of a certain type of comparison can increase without decreasing the use of other types.

The primary data of this study is 288 reviews of 254 Asian films released in the United States from 1985 to 2006. All released films were reviewed in the

For this research, we used mixed methods, combining content analysis and logistic regression. First, two of the authors conducted a content analysis to examine what type of comparison critics employ in their reviews. Any disagreements between the two coders were resolved through discussion among all authors. Next, based on the results of this content analysis, we used logistic regression to assess the effects of our explanatory variables on the likelihood of a critic drawing a certain type of comparison. Logistic regression analysis is appropriate for our binary dependent variables described below. We used SPSS 15.0 to estimate a set of logistic regression models.

The dependent variable is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether a critic’s review of an Asian film includes a comparison of the film, its director, or actors/actresses with their counterparts in the United States, home country, or other foreign countries, as described above. Accordingly we created three dependent variables—U.S. comparison, home comparison, and foreign comparison—for three separate regression analyses. Each dependent variable takes a value of “1” for a review including any kind of comparison (e.g., films, directors, and actors/actresses) and a value of “0” for no comparison. Our data shows that almost half (48.3%) of the

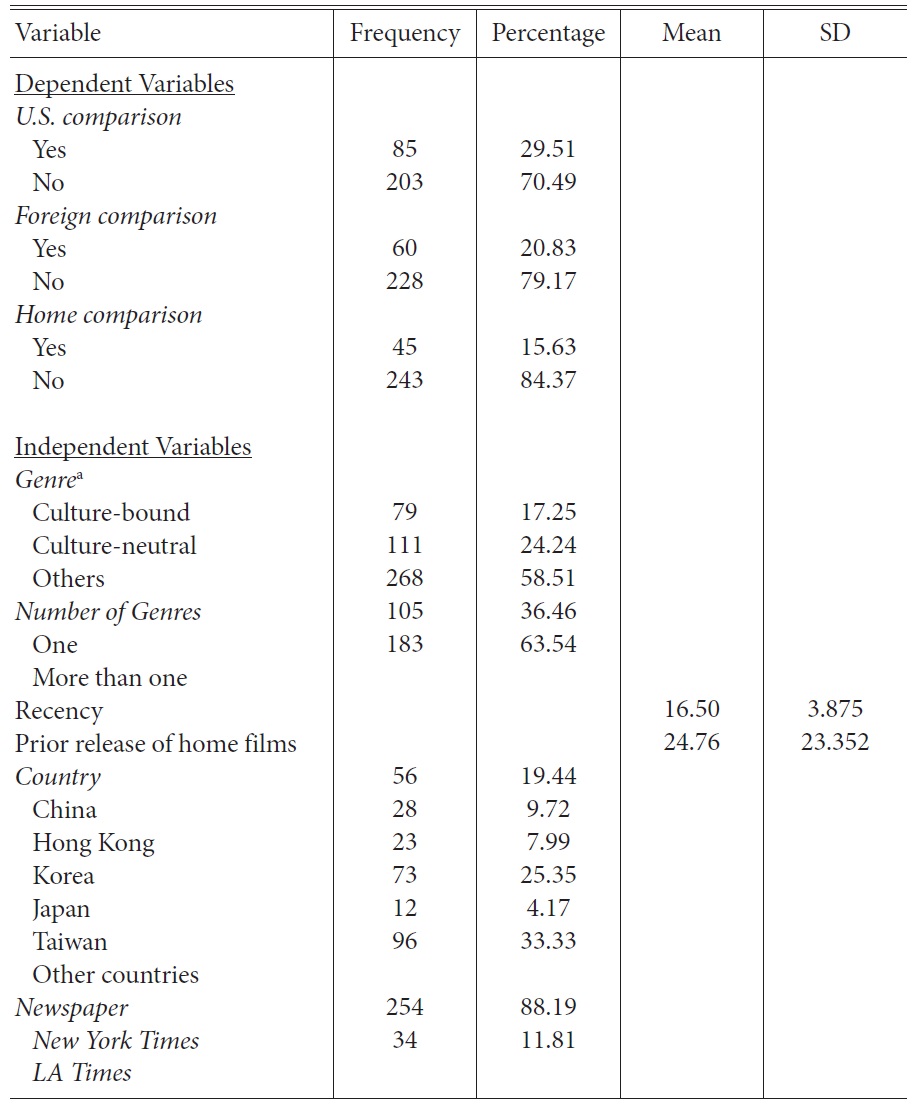

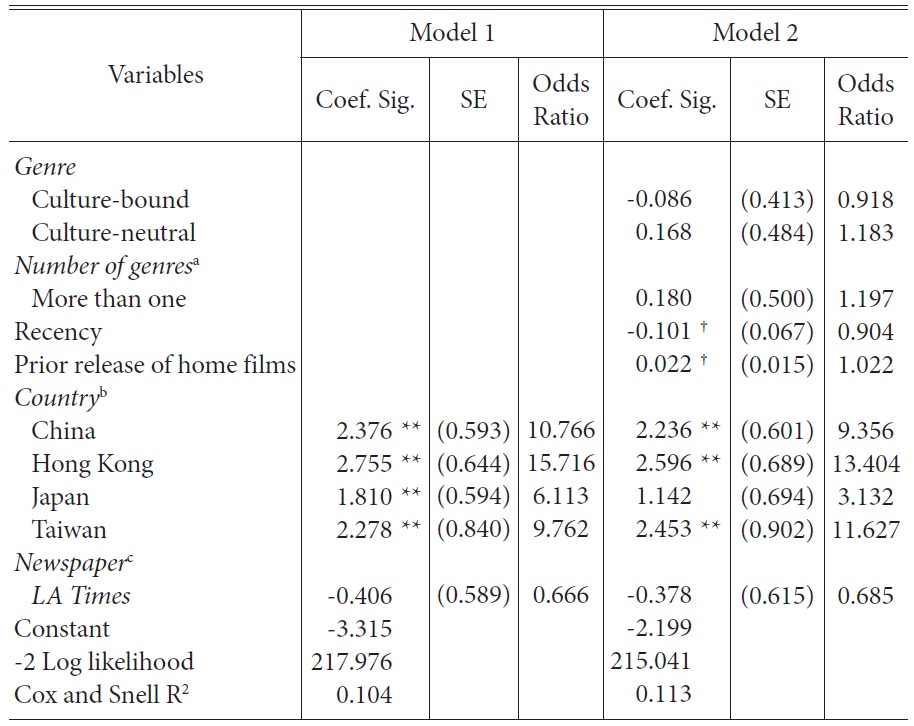

[Table 1] Summary Statistics for Dependent and Independent Variables

Summary Statistics for Dependent and Independent Variables

We presented four factors that can affect our dependent variables: genre, multiplicity of genre, prior release of home films, and recency. In our measure of genre, we follow the genre classification Hsu (2006a) proposed based on her investigation into three archival sources: Internet Movie Database, RottenTomatoes.com, and Showbizdata.com. According to her genre classification, films are classified into 17 genres: action, adventure, animation, comedy, crime, documentary, drama, family, fantasy, horror, musical, mystery, romance, science fiction, thriller, war, and western. For our study, we use 16 genres and exclude the western genre because it does not exist in Asian films. Building on this classification of 16 genres, film genres assigned to each Asian film are coded by referring to the genre information provided by IMDb.

To test hypothesis 1

In our analysis, we created two dummy variables, “culture-bound” and “culture-neutral,” which are coded “1” if an Asian film includes culturebound or culture-neutral genres, and “0” if not. Note that a film involves multiple genres, and the two dummy variables are not mutually exclusive. Thus, the effect of each dummy variable should be interpreted as that of including a particular type of genre on the likelihood of a critic drawing a comparison, as opposed to the effect of including other types of genres.

To test hypothesis 2, multiplicity of genres, a dummy variable was categorized into two groups: films affiliated with a single genre, and films affiliated with more than one genre. Multiple genre films are coded “1,” with single genre films as a reference category.6 For this variable, we used the IMDb information about the number of genres assigned to each film based on the classification of the 16 genres described above.

To test hypothesis 3

To test hypothesis 4

Since the predictions presented by our hypotheses can be affected by the country-specific features of a film, we included country dummies in our analysis of all reviews of Asian films. Focus on the East Asian region, countries were categorized into six groups for the models of U.S. comparison and foreign comparison: China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and all other countries consisting of India, Iran, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Bhutan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Singapore. However, South Korea was classified into the category of “other countries” for the model of home comparison because reviews of South Korean films had no home comparison in our sample. Each category of country is a dummy variable and the category of other countries is the omitted variable in our analyses. Finally, since the

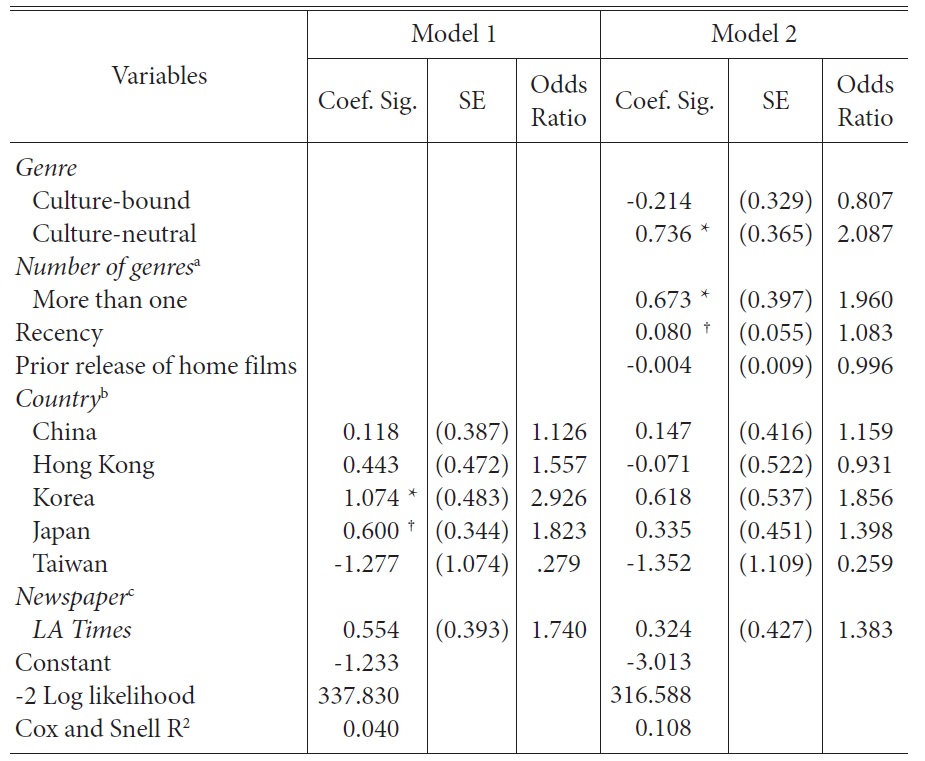

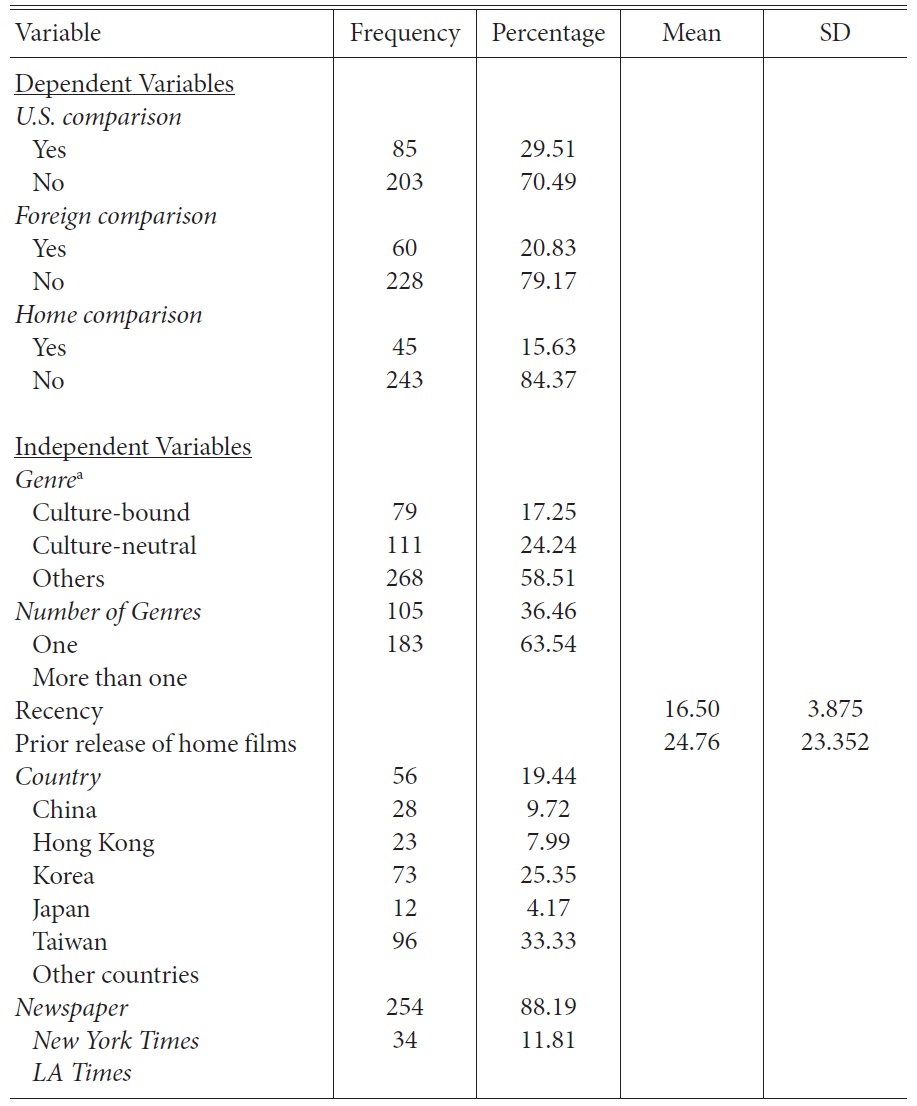

[Table 2] Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting U.S. Comparison

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting U.S. Comparison

Table 1 displays detailed information about the frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations for our dependent, independent, and control variables.

3The website of IMDb is http://www.imdb.com, that of the New York Times is http://www.nytimes.com/ref/movies/reviews/index.html, and that of the Los Angeles Times is http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/reviews/movies/. 4As of 2006, circulation of the New York Times and the LA Times were ranked third and fourth in the U.S., espectively, next to The Wall Street Journal (first) and USA Today (second). 5See http://pro.imdb.com. 6In a set of separate analyses, we employed different numbers for dummy categories and found that single versus multiple genres is the most significant distinction affecting critics’ use of a comparison. We also used a continuous variable, but its effects were less significant, leading to poorer model fit in the regression analyses.

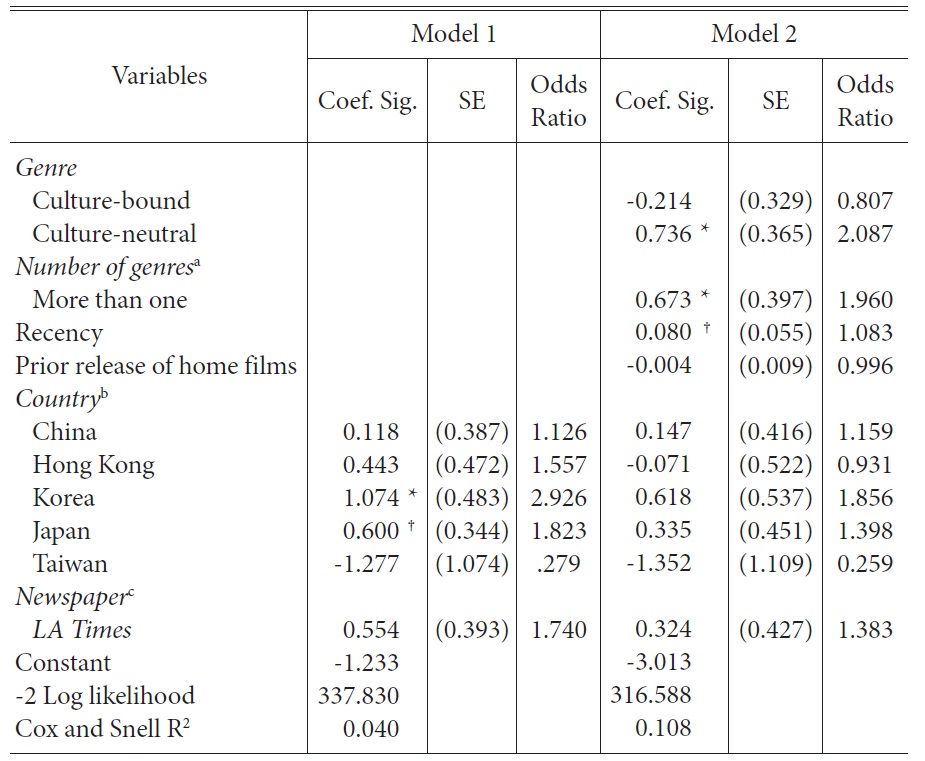

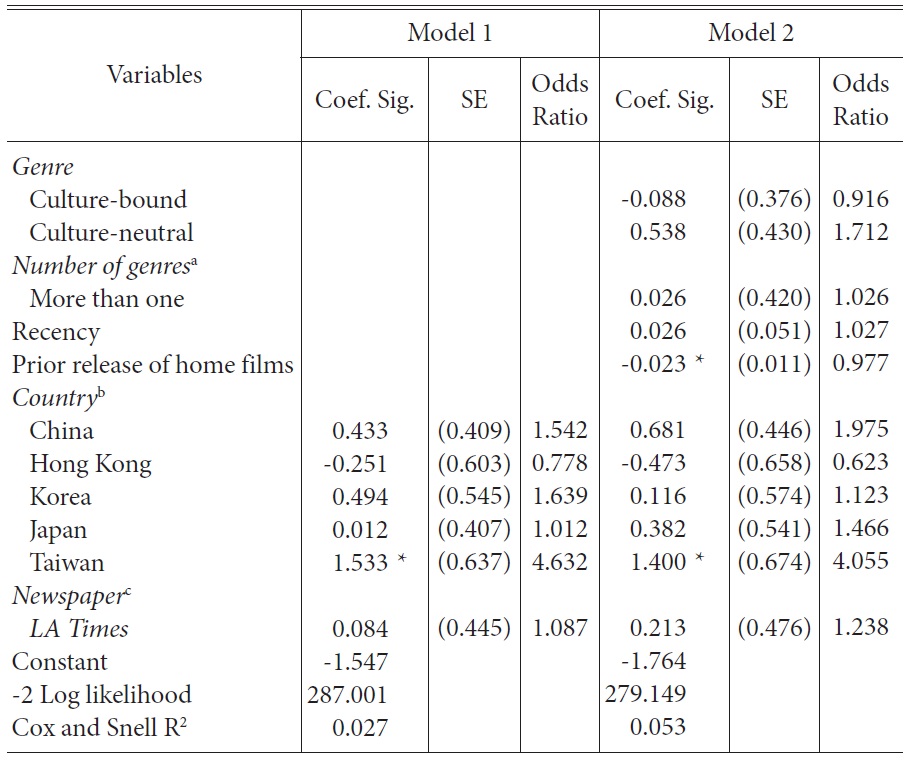

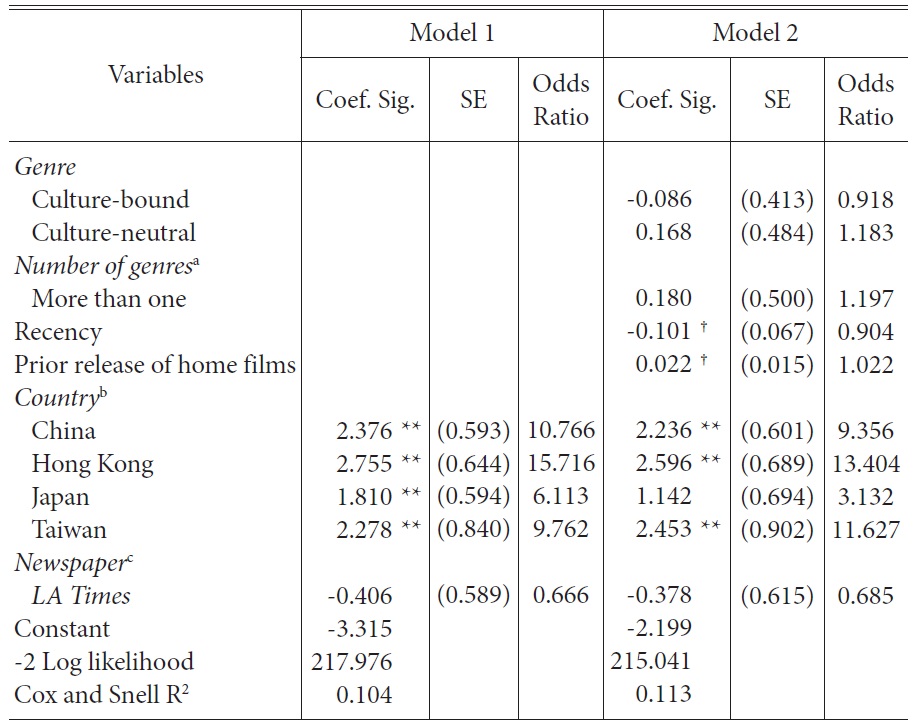

Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the results of the logistic regressions in which we examined several factors affecting the three types of comparisons—table 2 is for U.S. comparison, table 3 for foreign comparison, and table 4 for home comparison.

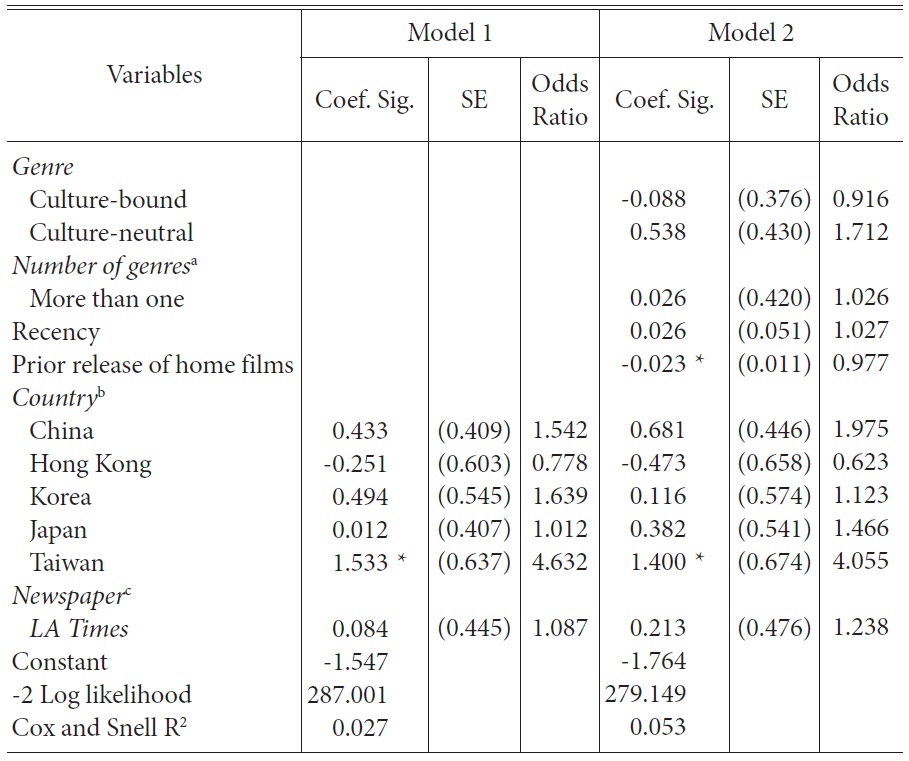

[Table 3] Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting Foreign Comparison

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting Foreign Comparison

Model 1 in each table displays the effect of countries and newspapers on the likelihood that critics will use a particular type of comparison. Across all types of comparisons (tables 2, 3, and 4), there are no significant differences between the

[Table 4] Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting Home Comparison

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting Home Comparison

Model 1 in table 3 shows that being from Taiwan has a significant and positive effect, indicating that critics are likely to make more foreign comparison for films from Taiwan. This effect remains unchanged when other variables are included in model 2. Model 1 in table 4 shows that the effects of originating from all of the four East Asian countries (China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan) are significant and positive, indicating that critics are more likely to make home comparison in their reviews of films from Pan-Chinese countries and Japan, in contrast with films from other countries (including Korea). However, when our independent variables are included in model 2, the effect of being from Japan on home comparison becomes insignificant. Overall, the effects of a film’s country of origin on U.S. and foreign comparisons are largely explained by other variables, although the use of home comparison is mainly explained by a film’s country of origin.

Model 2 in each table shows the effects of our four main independent variables, which are examined to see whether our hypotheses are supported or not.

We expected Asian films in culture-bound genres to be more likely to lead critics to draw home comparison (hypothesis 1

>

Effect of the Number of Genres

In hypothesis 2, we anticipated that Asian films with multiple genres are more likely to lead critics to induce comparison strategies than those with a single genre, regardless of the type of comparison. The results show that this hypothesis is supported for U.S. comparison. As shown in table 2, involvement of more than one genre produces significant and positive effect, indicating that critics tend to use more U.S. comparison for films with multiple genres than for single genre films. As for tables 3 and 4, the effect of belonging to more than one genre on foreign and home comparisons is insignificant, although the direction of the effect is consistent with our predictions.

>

Effect of Prior Release of Home Films

We expected greater number of prior home films released in the Unites States to increase the likelihood of critics to utilize home comparison (hypothesis 3

Finally, we anticipated that the more recently released Asian films in the United States would increase the likelihood of critics using U.S. or foreign comparison (hypothesis 4

This article explored several factors shaping American critics’ comparison strategies in their review of Asian films, which are designed to help reduce the uncertainty the U.S. audiences feel toward Asian films. From the archives of the

We also found that U.S. critics tend to induce less foreign comparisons and more home comparisons when there are abundant prior home films released in the United States. This suggests that critics tend to rely less on foreign films when reviewing Asian films with a large pool of prior home films released in the United States that contains sufficient counterparts for more effective comparisons, whether they compare directors, actors/actresses, or the overall nature of the films. In addition, our finding that critics significantly tend to draw home comparison for films from pan-Chinese countries and this effect persists even when our key variables are included in the model may suggest that U.S. critics realize that American audiences are more familiar with films from those countries than films from other Asian countries.

Overall, we believe that our quantitative analyses make further contributions toward existing literature on economic sociology, cultural sociology, and organizational studies by showing how some features of foreign cultural products and the historical background of those products in the domestic market affect the ways in which a market mediator influences and shapes domestic audiences’ understanding of those products.

Broader implications for literature can also be derived from our study. First, this study extends its analytic focus beyond products in a single national market by investigating how foreign cultural products, which were initially produced to meet the demand of their home market, are perceived and evaluated in other markets—the U.S. market in this case. Few studies pay attention to what will happen if cultural products transfer from one national market to another national market, and this study serves as a novel attempt to demonstrate the role of evaluators in the receiving market (e.g., critics in the U.S.) in absorbing and channeling foreign cultural products.

Second, this study demonstrates that various types of comparison strategies used by critics may affect globalization of the film industry. The advent and growth of globalization certainly creates demand for the role of gatekeepers. Through the evaluation of products from foreign countries, on the one hand, gatekeepers can increase the rapport between domestic consumers and foreign products as well as facilitate transactions between countries. On the other hand, they can highlight the distance between foreign products and domestic taste, raising the hurdle that exists between the countries. This study further shows how different national markets interact with the cultural products market. Examining film critics’ review strategies appears to help show one instance of such interaction.

However, our study also contains some limitations which we should leave to future research to overcome. First of all, the sample size should be increased by collecting critics’ reviews of Asian films from more newspapers such as the