Great attention has been given to the questions of the influence from language learners’ mother tongue (L1) on language acquisition in the context of SLS, as in the case of the positive transfer from L1, a variety of studies have been carried out on the negative transfer. However, approaches regarding the concept of

However, there is no overall agreement supporting this perspective as to the broad boundaries of language background. Saville-Troike (2006) does not fully agree with the practice of applying numerical measurements to the concept of multilingualism and multiple language acquisition. In his assumption, he confined the concept of multilingualism as a binary system in which uses the terms ‘monolingual’ and ‘bilingual’ with bilingual defined as knowing two or

Yet, it requires further examination with regard to certain aspects of ‘multilingualism’. For example, a series of studies on multilingualism stand in sharp opposition to the binary approach supported by Saville-Troike (2006), Ringbom (1987), and Llisterri & Poch (1987). Based on the assumption that multi-language users’ language capabilities are different from monolinguals, these studies undermine the assumptions of the binary approach by constantly reporting the conciliatory and neutral effects from

The validity of L3 research is directly prefigured by the fact that many language learners are practicing their target languages as an additional language, not as a second language. Due to the fact that about more than half of the world’s population is constantly exposed to multi-cultural environments to the extent that exposure influences language using experiences (Hammarberg, 2010) and due to the rise of English as a lingua franca, the bilingual environment is no longer a unique phenomenon and many languages are being learned as an additional language, not as an L2 (Baek, 2012). The influence of L2 on L3 is most noticeable in the language acquisition of adult learners. It is directly, consistently linked to the strategies using previously acquired language knowledge to avoid cognitive and psychological pressure (Williams & Hammarberg, 1998; Dewaele, 1998, 2009; Lindqvist, 2009; Letica & Mardesic, 2009; Iverson, 2010). Likewise, the discussion about the process of L3 acquisition should be examined separately from the context of ‘bilingualism’ since bilingualism usually focuses on the relation between L1 and L2, while L3 refers to more complex language acquisition situations encompassing three or more languages. These intricate situations can be postulated to at least four possibilities according to the chronological order of acquisition of languages (Cenoz, 2000).

The issues of prior knowledge of multilinguals in the process of learning subsequent languages have begun to be investigated from various angles and it seems they will remain central to future studies as well (Mayo, 2012). The beginning of the present century is marked by the intense debate on the uniqueness of the trilingualism research and a significant increase in the number of studies on multilingualism and cross-linguistic Influence (CLI). CLI is a certain tendency activating L2 in L3 performance while it suppresses L1 (Hammaberg, 2001). Following the early research of CLI (Ringbom, 1987; Llisterri & Poch, 1987), the influence from L1 was mainly focused on explaining the aspects of language acquisition of Spanish learners in Basque and Catalunya. However, following the seminal work conducted by Hammaberg (2001), researchers have reached nearly universal consensus that the influence from L2 can compensate and neutralize L1, as L1 is suppressed for its ‘non-foreign status’.

Before we embark upon an analysis of CLI, we need to pause to note the general limitations found from previous L3 research. It should be pointed out that most of the existing L3 studies have been conducted through experimental designs which lack proper consideration of the typological distance between the target languages. This limitation deserves our attention because the target languages in the experiments consist mostly of European languages sharing many linguistic similarities with each other. Hence, the validity of the experiments is marred somewhat by the uncontrolled typological distance (Rothman, 2010a; Mayo, 2012). In this study, I will endeavor to infer from Rothman (2010a)’s assertion regarding experiment design by setting languages (Chinese-English-Korean) which do not have typological similarities.

It should be noted that no indication is provided as to the difference of the learners with previous acquired foreign languages before Korean. Thus, this study provides an in-depth view of the uniqueness of multilingual Korean learners in classroom settings by providing the illustration of syllable perception. Great attention has been shown to the question of L1-L2 processing according to the difference of mother language backgrounds of Korean learners, however, Korean teachers have paid scant attention to the multi-layered language background of their students. This study will broaden the teachers’ perspective on learners’ stereoscopic language backgrounds and multilingualism which were largely ignored in the area of Korean education.

2. Research Background and Purpose of Study

2.1. L1 influence over L2 syllable identification

It has been noted that English and Chinese phonology differ mainly in the complexity of their syllable structures. While English phonology allows highly complex syllable structures, Chinese syllables typically consist of only a consonant and vowel (CV). This contrast is hypothesized to promote different phonological processing units in the two languages. Due to negative L1 transfer, the inferior phonological awareness can be observed in Chinese ESL learners (Chen et al, 2002, 2003; Chen 2006). The same logic applies in the comparison of Chinese and Korean. Superior phonological awareness from Korean speakers has been constantly reported in a series of syllable judgment tasks conducted among Chinese and Korean speakers learning English as a second language (ESL). Thus, it has been interpreted that positive transfer may occur between languages which share the same degree of complexity in syllables (Wang & Koda, 2007). The results of the previous studies imply that the perceived difficulty of learning coda in Korean syllables may differ by the L1 of KSL learners.

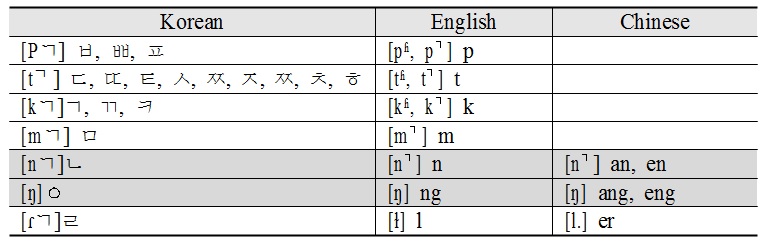

It has been supported that L1 transfer of phonological processing units can be so measured with the number of phonemes in coda. Korean coda has a rather wide selection of phonemes (/p/, /t/, /k/, /n/, /m/, /ŋ/, /ɾ/) which are largely shared by English. In a Chinese syllable, however, the coda is limited to two nasal phonemes only: namely, /n/ and /ŋ/. Since even these scant options are restricted by combination constraint, it would be highly probable that Chinese KSL learners would have much difficulty in identifying Korean syllables.

In connection with the hypothesis above, the studies on syllable awareness in the context of Korean education are heavily charged with L1-L2 studies. Though these studies successfully delved into the influence from L1 to L2, they failed to answer the questions about the influence of L2 to L3 in language acquisition. However, considering the fact that numerous KSL learners are studying Korean as an additional language other than L2, multilingual acquisition including L2-L3 process should be thoroughly examined with carefully designed stereoscopic experiments.

For example, it is clear from the above that Chinese-English bilingual speakers who acquired English as a longstanding L2 in their critical period can expect the positive transfer effects from English which might be overwhelmingly predominant over L1. Namely, it is reasonable to conceive that Chinese-English speakers will show a superior ability to perceive and distinguish Korean syllables than their counterpart Chinese monolingual speakers. Moreover, the bilingual group’s performance would be expected to be as good as the English monolingual group’s if CLI (Cross Linguistics Influence) from L2 (English) is sufficient to compensate for L1 (Chinese) influence. As an example, Llama et al (2007) reported the additive effects of L2 (French) over L1 (English) on the acquisition of L3 (Spanish) voiceless stop phonemes such as /p, t, k/. In the case of Collazos (2011) regarding the acquisition of Spanish diphthongs, the L1 (Japanese) was compensated by L2 (English).

No less significant is the type of syllables. This could explain the effect of the types of input possibly differentiating the performances of each group of participants. In this experiment, four syllabic conditions are embedded to investigate the influence of the types of input participants receive: CV-CV, CV-CVC, CVC-CV, CVC-CVC. If the performances of syllabic conditions differ according to each group, then this result suggests the differences in syllable judgment are not solely confined at the quantitative level (average respond time), but also at the qualitative level (preferred syllable conditions). To put it differently, if the response modalities between Chinese-English bilingual group and English monolingual group are identical, but variant from the Chinese monolingual group, this result can be interpreted to mean that the L2 (English) factor can affect not only the performance at the general level but also qualitative aspects as well. Conversely, we need to consider the opposite interpretation when the bilingual group’s results are rather close to the Chinese monolingual group’s response pattern.

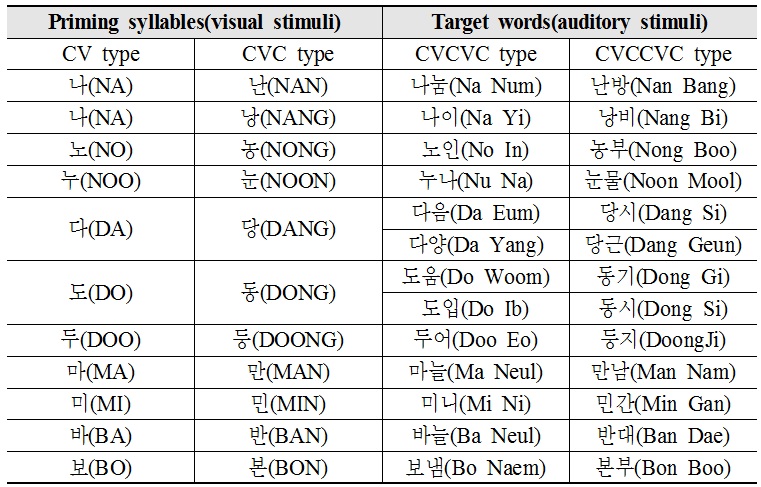

I designed ‘syllable judgment tasks’ referencing Mehler et al (1981), Segui (1986). The experiment was conducted using disyllabic Korean words in three novice level KSL groups to confirm the hypotheses discussed above; (1) Chinese monolinguals, (2) English monolinguals, and (3) Chinese-English bilinguals. Korean proficiency of all participants is limited to the novice level to preclude any possibilities of the intervention from Korean mental lexicon.

The experiment was conducted in December 2013 in three classes from the Institute of International Education (IIE) at Kyung-Hee University in Seoul, Korea, involving 24 learners total. All informants were in the first semester of a preliminary or beginner 1 course in Korean with less than 3 months of Korean learning experience. All participants’ ages were identified as early twenties except for three late teen participants in the Chinese-English bilingual group.

The following is a profile of the groups involved.

3.2. Materials and instrumentation

Target words consisted of 18 pairs of disyllable Korean words; each pair of words had three identical phonemes in common except for the final consonants of the second syllable. Also, diphthongs were not applied to the first syllable of the target words. Only the Korean words which did not require any kind of phonological changes were included in the experiment design to exclude the potential influence from phonological routes of mental lexicon. Also, only two phonemes ([nᄀ], [ŋ]) were used in the experiment among all seven available phonemes for the coda in Korean syllable combinations. Judging from the scant number of phonemes shared by Chinese, English and Korean, it would be erroneous to include all of seven phonemes ([Pᄀ], [tᄀ], [kᄀ], [mᄀ], [nᄀ], [ŋ], [ɾᄀ]) of Korean syllables. The experimental program used in this article was “Open Sesame 0.26 Earnest Einstein” developed by Sebastian Mathôt of Aix Marseille Université.

Participants were invited to reflect on their phonological searches. They were informed that both the priming syllables and first syllables in the target words which were to be compared with each other were differentiated by the existence of final consonants and that in a given list of trials, the 2 x 2 (priming syllables x target words) combinations of syllables were repeatedly presented.

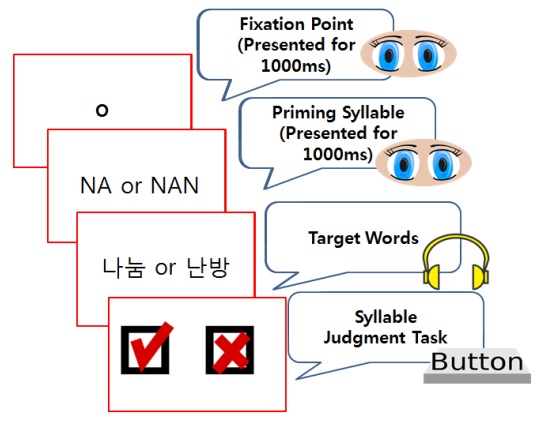

English and Korean stimuli were displayed in lower case letters at the center of the 11 inch monitor. A trial consisted of a fixation point for 1000 msec, and then a forward priming syllable for another 1000 msec followed by the target word. Contrast to other stimuli, a target word was presented in auditory form until the subject responded. Subjects received two blocks of 52 trials, presented in random order. They were asked to judge whether the priming syllables (visual stimuli) and the first syllables of the target words (auditory stimuli) are identical as fast as possible while trying not to make errors. If both syllables were identical, subjects had to press the key labeled “Y”, and if they were not identical, they had to press the key labeled “N”. The ratio between response selections of “yes” and “no” were counterbalanced across subjects. The stimuli presentation order is described in Figure 3.

Before analyzing response time, the analysis of accuracy rate was conducted. Since the equal variance of the data was not assumed [F(2, 1239) = 7.127, p = .001], Dunnett’s T3 test was applied as a post hoc test. As no statistically significant difference between the groups was found [F(2, 1239) = 1.732, p = .177], it is quite clear that there was no significant difference between the three groups in terms of accuracy rate.

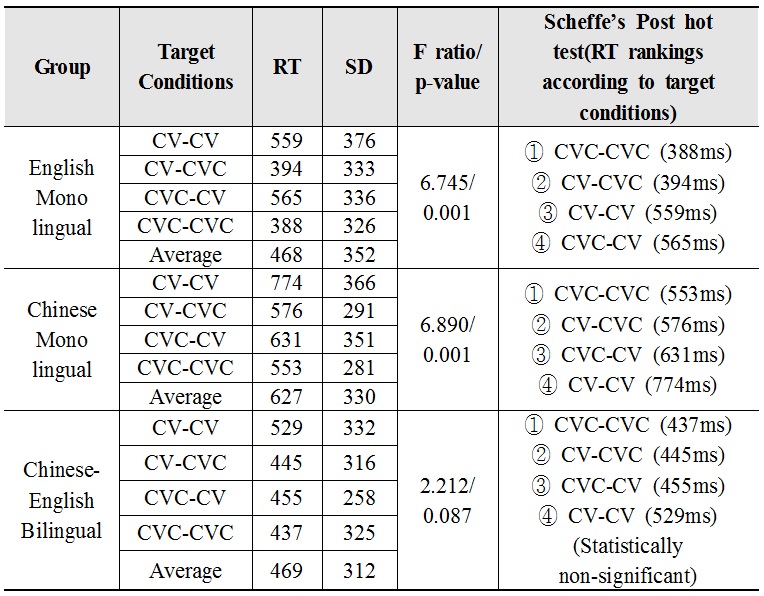

Next, response time (hereafter, referred to as RT) was statistically treated, Scheffe’s test was chosen as a post hoc test since the equal variance of the data was assumed [F(2, 949) = .438, p = .645]. Compared to the average RTs of the three subject groups without considering 2 x 2 (priming syllables x target words) syllable combinations, the English monolingual group showed the fastest RT among the three groups (468ms), the Chinese-English bilingual group came next (469ms), Chinese monolingual group was the slowest (627ms). This difference was confirmed to be statistically significant [F(2, 949) = 23.395, p = .000], however, the gap between the English monolingual group and the Chinese-English bilingual group was identified as non-significant at the statistical level. To summarize, the statistical data discussed above led to the conclusion that only the Chinese monolingual group was inferior to other groups in terms of RT. On the other hand, the English and bilingual groups’ RTs were found to positively correlate with CVC-CVC condition, but to negatively correlate to CV-CV condition. Syllable decision time latency for each of the prime conditions is shown in Figure 4.

Considering the inferior RT performance in syllable decision tasks acquired from the Chinese group to the English group, it is not unreasonable to postulate that there is significant L1 influence on L2 acquisition. Thus, our first research question concerning the influence of L1-L2 transfer is both theoretically and empirically supported. This result is consistent with earlier research conducted in the area of L1-L2 syllable studies in Korean education. Of note is that while this study’s RT results were consistent with those of previous studies, the experimental results regarding accuracy rate presented no significant difference between the groups and thus does not support L1 factor’s influence on L2 processing. To my knowledge, this inconsistency was caused by the unique experimental design that I applied in this study. Most previous research conducted targeting KSL learners is methodologically focused on acquiring accuracy rates from the subjects. Thus they included all of seven Korean final consonants in their experiment design ([Pᄀ], [tᄀ], [kᄀ], [mᄀ], [nᄀ], [ŋ], [ɾᄀ]), whereas I included only two final consonants ([nᄀ], [ŋ]) to concentrate on RT rather than accuracy rate data. To speak in L1-L2 acquisition context, many studies have reported that Korean final consonants which are not shared by the Chinese sound system such as [Pᄀ], [tᄀ], [kᄀ], [mᄀ], [ɾᄀ] are the main obstructive factors in KSL context causing numerous errors and inferior results in syllable decision tasks (Yang, 2006; Kwon, 2012). Consequently, if I included any Korean phonemes other than [nᄀ], [ŋ], it would be difficult to avoid getting inferior results from the Chinese monolingual group. However, it should be reiterated that these results are rather biased since [Pᄀ], [tᄀ], [kᄀ], [mᄀ], [ɾᄀ] are shared by only Korean and English, leading English KSL learners to produce superior performance without difficulty. Therefore, it made sense to include only [nᄀ] and [ŋ] in the experiment as these are all shared by Korean, English and Chinese as well.

Admittedly, the uniquely designed experiment in this article led to no significant difference between the groups in terms of accuracy rate. Again, the homogeneous results in accuracy are expected from the experiment design which included only two phonemes ([nᄀ], [ŋ]) as final consonants to control the error rates from Chinese monolingual group. However, we can still find the inferior results from the Chinese monolingual group in the aspect of RT, which suggests that the inferior performance of Chinese speakers in syllable decision tasks is caused by the complexity of their L1 syllable structures, not by the scant options of Chinese phonemes in coda position.

Our second research hypothesis concerning L2-L3 processing, that Chinese-English bilingual KSL learners would be accord with English monolingual counterparts in syllable judgment tasks in terms of response time, accuracy, and response modality is partially supported by the results of the experiment. First, since the accuracy rate between all three groups was found to be statistically equivalent as discussed above, it is hard to escape the conclusion that there is no sufficient resource of information for assessing this specific question.

Second, as to response time, the hypothesis is strongly supported by the acquired data from the experiment. The Chinese monolingual subjects’ results with regard to syllable decision tasks were substantially inferior to other subject groups, and the bilingual group and the English monolingual group showed almost identical response time (E: 468msec, C-E: 469msec). Thus, it is justifiable to conclude that L2 factor can neutralize the negative transfer from L1 on acquisition of L3 phonology in a Korean learning context. This interpretation provides strong evidence that L3 research which is itself a rich assembly of studies of European languages can also be applied to Eastern Asian languages such as Korean and Chinese.

Third, although we successfully found the results supporting L2 effects on L3 acquisition in terms of average RT, these results should be viewed with reservation when it comes to response modality. Though it was not statistically proven, the Chinese-English bilingual group, like the Chinese monolingual group tended to have their lowest scores in CV-CV conditions. The English monolingual group, however, showed their lowest results in CVC-CV conditions. Given these data interpretations, it appears likely to us that the task performance of Chinese-English bilingual group which can be estimated by average RT is similar to English monolingual group’s, whereas the most preferred syllable condition by bilingual group is also become preferred by Chinese monolingual group. It would not be unreasonable to say, therefore, that L2 holds significant influence on syllable judgment performance as a general rule, however, L1 effects can still be present when it comes to the specific response modality.

My aim in this article was in no way focusing on L1-L2 processing which has attracted much attention as a research subject of SLS, but rather to employ a wide perspective by referencing research topics about L3 studies. This article has attempted to design stereoscopic experiments including East Asian languages to sketch out the main characteristics of L3 studies in the context of Korean education. This offers the methodological benefit of ensuring experiments with unmatched construct validity by avoiding the potential dangers of ‘language pair problem’ caused by the uncontrolled typological distance of the languages in experiments. Also, it has to be reiterated that the significantly low target language proficiency of all participants enabled me to control the potential deviations in experiment results caused by the proficiency gap between individuals.

Central to this study have been the questions of L2 influence on L3 acquisition and its effects in neutralizing L1 influence. From the evidence at hand, I conclude that L1 influence has been found to be overwhelmed by L2 influence as a general rule. However, if we deeply delve into the specific syllable conditions that each group of subjects performed at their best, it is reasonable to assume that L1 influence still has remained at deeper domain levels.

One conclusion we can draw from this discussion is that this study lays the foundation for future work on L3 studies in Korean education by proving the overwhelming influence of the previously acquired foreign languages (L2) over mother tongue (L1) on the acquisition of target language (L3). We cannot, therefore, avoid the prediction that there can be significant deviations in auditory awareness among learners who share the same mother tongue when their L2 learning experience is drastically deviated. This brings me to a final comment: the language development and acquisition of multilingual populations should be independently discussed from previous L1-L2 acquisition studies.